Chapter 1

Introduction

Wolff-Michael Roth and Kadriye Ercikan

A fundamental presupposition in cultural-historical activity theory—an increasingly used framework for understanding complex practical activities, interventions, and technologies in schools and other workplaces (e.g., Roth & Lee, 2007)—is that one cannot understand some social situation or product of labor without taking into account the history of the culture that gave rise to the phenomenon. This book, too, can be understood only within the particulars of some fortunate events that brought us, the two editors, together in quite unpredictable ways. From this coming together emerged a series of collaborative efforts in which we, normally concerned with teaching quantitative and qualitative methods, respectively, began to think about educational research more broadly and transcending the traditional boundaries around doing inferential statistics and designing (quasi-) experiments and doing various forms of naturalistic inquiry.

Some time during the early part of 2004, King Beach and Betsy Becker approached the two of us independently inviting us to co-author a chapter for a section in a handbook of educational research that they edited. Kadriye works in the program area of measurement, evaluation, and research methodology and focuses on psychometric issues; Michael, though trained as a statistician, teaches courses in interpretive inquiry. Despite or perhaps because of the apparent differences, we both tentatively agreed and, soon thereafter, met when Michael participated at a conference in Vancouver, the city where Kadriye’s university is located. During the subsequent months, we interacted both on the phone, via e-mail, and through our mutual engagement with each other’s texts and contributions to the joint endeavor. The collaboration as process and our final product on “Constructing Data” (Ercikan & Roth, 2006a) both provided us with such a great satisfaction that we soon thereafter decided to work together on another project, this time dealing with one of the issues that had emerged from our collaboration: the apparent opposition of “quantitative” and “qualitative” approaches in educational research, which in the past has lead to insurmountable conflicts and paradigm wars. We, however, had felt while writing the handbook chapter that there are possibilities for individuals such as ourselves with different research agendas and methods to interact collegially and productively. We decided to grabble with the question, “What good is polarizing research into qualitative and quantitative?” and to report the outcome of our collaborative investigation to a large audience of educators (Ercikan & Roth, 2006b).

In the process of working on the question, we came to argue against polarizing research into quantitative and qualitative categories or into the associated categories of subjective and objective forms of research. We demonstrated that this polarization is not meaningful or productive for our enterprise, educational research. We then proposed an integrated approach to education research inquiry that occurs along a continuum instead of a dichotomy of generalizability. We suggested that this continuum of generalizability may be a function of the types of research questions asked; and it is these questions that ought to determine the modes of inquiry rather than any a priori questions about the modes of inquiry—which drives the “monomaniacs” (Bourdieu, 1992) of method, which build entire schools and research traditions around one technique.

As during our first collaborative venture, we emerged from this experience both satisfied to have conducted a conversation across what often is perceived to be a grand divide and to have achieved a worthwhile result. Not soon after completion, we began talking about a special issue in a journal that would assemble leading scholars in the field discussing the issues surrounding generalization in and from educational research. But it became quite clear in our early discussions that the format of a journal issue would be limiting the number of people we could involve and the formats that the individual pieces could take. It also would limit us in producing the kind of coherent work that we present in this book, where chapters are bundled into sections, with an all encompassing narrative that provides linkages between chapters and starting points for further discussion. Our motive for this book, elaborated in the following section, was to have our contributors think about questions arising for them in the endeavor to generalize from educational research with the aim of going beyond the dichotomous opposition of quantitative and qualitative research method.

Beyond the Quantitative—Qualitative Oppositions

The discussion concerning the generalizability was sharpened with and in the debate between what came to be two camps, those doing statistics and denoting their work as “quantitative” and those doing other forms of inquiry denoted by the term “qualitative” or “naturalistic.” The discussion was polarized, among others, in Yvonna Lincoln and Egon Guba’s (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry, where the “naturalist paradigm” was presented to be the polar opposite to “positivist paradigm.” Accordingly, naturalists were said to have difficulties with the concept of external validity, that is, the generalizability of research-generated knowledge beyond the context of its application. The transferability of findings made in one context to some other context was taken to be an empirical matter rather than one that could be assumed based on statistical inference, even with its safeguards of estimating the probability of type I and type II errors. The classical position assumed that given high internal validity in some sample A and given the sample is representative of the population P, then findings made in the sample A could be generalized to the population P as a whole, and, therefore, to all other samples that might be taken from it.

The so-called naturalists rejected this form of generalization. One of the main points of the rejection is grounded in the very idea of a population. Guba and Lincoln remind their readers that inferences about populations can be improved with the specification of “homogeneous strata.” But this in fact constitutes a specification of context and contextualization of knowledge. This therefore raises the issue about the extent to which something found in some inner-city school district in Miami can be used to inform teaching and learning in inner-city Philadelphia or New York, i.e., the three cities where one of our chapter authors, Kenneth Tobin, has conducted detailed studies of teaching and learning science. Concerning teaching, we know from detailed ethnographic work that a Cuban-African American science teacher highly successful in inner-city Miami was unsuccessful in his own account teaching science to “equivalent” students in inner-city Philadelphia. But the same teacher, much more quickly than other (novice) teachers, became a highly effective teacher in this for his new environment. Thus, his practical knowledge of teaching science to disadvantaged students turned out to be both transferable and non-transferable.

The discussion concerning the generalizability of educational research in the United States has heated up again during the George W. Bush era, when policy makers declared that experimental design constituted the “gold standard” of (educational) research. All other forms of research generally and “qualitative research” more specifically, were denigrated as inferior. In this book, we invited well-established and renowned researchers across the entire spectrum of educational research methods to weigh in on the question concerning the extent to which educational research can be generalized and transported (transferred) to other contexts.

Generalization and generalizability are gaining more importance with increased levels of scrutiny of value and utility of different types of educational research by funding agencies, the public, educational community and researchers themselves. These aspects of educational research have come to define the utility and quality of research in education and have also come to further polarize conceptualizations of educational research methods (Shaffer & Serlin, 2004). In light of the present political debates about the usefulness of different kinds of research (e.g., the “gold standard”), the issue of generalizability is often entered into the discussion as a criterion to argue for one form of research as superior over another. Typically, the scholarly (and political) discussion of degrees of generalizability is inherently associated with statistical (i.e., “quantitative”) approaches and commonly questions the generalizability of observational (i.e., “qualitative”) approaches. Unlike often assumed, we argued in our Educational Researcher feature article that a quantitative—qualitative distinction does not correspond to a distinction of the presence and absence of generalizability (Ercikan & Roth, 2006b). Rather, there are “qualitative” forms of research with high levels of generalizability and there are “quantitative” forms of research with rather low levels of generalizability. In addition, we argued and demonstrated that research limited to polar ends of a continuum of a variety of research methods, such as experimental design in evaluating effectiveness of intervention programs, in fact can have critically limited generalizability to decision making about sub-groups or individuals in intervention contexts.

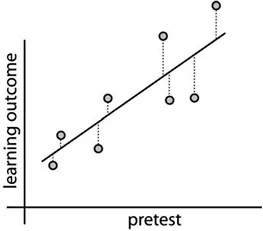

One of the central issues may be the usefulness of different types of data and descriptions useful to different stakeholders in the educational enterprise. Thus, the following graphical representation that a researcher may have constructed to correlate the performance on a pre-test with scores indicating a particular learning outcome. Whereas the pretest might be consistent with published research and therefore reproduce existing (statistically reliable) relationships with the learning outcome variable, knowing the correlation actually helps a classroom teacher very little.

Figure 1.1 Correlation between pretest and learning outcomes.

The teacher, to design appropriate instruction for individual students, is interested precisely in the variation from the trend, that is, she is interested in the variation that in statistical approaches constitutes error variance. That is, to properly inform this teacher on what to do in her classroom, we need to provide her with forms of knowledge that are simultaneously sufficiently general to provide her with trends and with forms of knowledge that are sufficiently specific to allow her to design instructions to the specific needs expressed in the variation from the trend.

This book is designed to address these issues in a comprehensive way, drawing on the expertise of leading, well-known researchers in the fields traditionally characterized by the adjectives qualitative and quantitative research. The purpose of this book is twofold: (a) to work out and present an integrated approach to educational research inquiry by aiming at a continuum instead of a dichotomy of generalizability, how this continuum might be related to types of research questions asked and how these questions should determine modes of inquiry; (b) to discuss and demonstrate contributions of different data types, and modes of research to generalizability of research findings and limitations of research findings in research that utilizes a single research approach.

Arguing against single-method research but for generalization, Pierre Bourdieu (1992) portrays analogical reasoning to be one of the powerful instruments of research. Analogical reasoning allows researchers to immerse themselves in the particularities of their cases without drowning in them—a familiar experience to many novice researchers. As Bourdieu elaborates, analogical reasoning realizes generalization

not through the extraneous and artificial application of formal and empty conceptual constructions, but through this particular manner of thinking the particular case which consists of actually thinking it as such. This mode of thinking fully accomplishes itself logically in and through the comparative method that allows you to think relationally a particular case constitutes as a “particular instance of the possible” by resting on the structural homologies that exist between different fields … or between different states of the same field. (p. 234)

In the course of this book, we work toward such a conception of generalization in educational research, as outlined in more or less the same form in the chapter by Wolff-Michael Roth, who takes a similar dialectical perspective as Bourdieu though grounded in and arising from a different scholarly context.

Most importantly, this book not only is about generalizing from educational research but also is and arose from the self-questioning accomplished researchers engaged in when we asked them to address the question at the heart of this book. We emerge from this work with a sense that there is a lot of recognition for the different problems arising from different forms of inquiry, a mutual respect, and a desire to continue to contribute to resolving the hard question: how to make research relevant to all stakeholders in the educational enterprise.

Structure and Content

This book consists of 11 chapters clustered into four sections: “Generalizing Within and Beyond Populations and Contexts,” “Combining and Contrasting Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence,” “How Research Use Mediates Generalization,” and “Rethinking the Relationship Between the General and the Particular.” Each section begins with an overview text presenting and contextualizing the main ideas that gather the chapters in the section. Each section is completed by concluding comments by the editors that highlight issues covered in the section. At the end of the four sections is a discussion chapter of a set of key issues that cut-across all the chapters. These discussions among the contributing authors and the editors are targeted to addressing three key questions:

- How do you define “generalization” and “generalizing”? What is the relationship between audiences of generalizations and the users? Who are the generalizations for? For what purpose? Are there different forms and processes of generalization? Is it possible to generalize from small scale studies?

- What types of validity arguments are needed for generalizing in education research? Are these forms of arguments different for different forms of generalization? Can there be common ground for different generalizability arguments?

- Given that “qualitative researchers” may count objects and members in categories and even use descriptive statistics: Do “qualitative” and “quantitative” labels serve a useful function for education researchers? Should we continue to use these labels? Do you have suggestions for alternatives, including not having dichotomous label possibilities?

The purpose of the discussion chapter is to highlight the salient issues arising from the chapters and to move our understanding to the next higher level given that each chapter constitutes a first level of learning. Taken as a whole, the introduction, overviews and highlights and the discussion chapter constitute the main narrative of this book in which the individual arguments are embedded. This main narrative, to use an analogy, is like the body of a pendant or crown that holds together and prominently features all the diamonds and other jewels that make the piece of jewelry.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1992). The practice of reflexive sociology (The Paris workshop). In P. Bourdieu & L. J. D. Wacquant, An invitation to reflexive sociology (pp. 216–260). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ercikan, K., & Roth, W.-M. (2006a). Constructing data. In C. Conrad & R. Serlin (Eds.), SAGE handbook for research in education: Engaging ideas and enriching inquiry (pp. 451–475). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ercikan, K., & Roth, W.-M. (2006b). What good is polarizing research into qualitative and quantitative? Educational Researcher, 35(5), 14–23.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Roth, W.-M., & Lee, Y. J. (2007). “Vygotsky’s neglected legacy”: Cultural-historical activity theory. Review of Educational Research, 77, 186–232.

Shaffer, D. W., & Serlin, R. C. (2004). What good are statistics that don’t generalize? Educational Researcher, 33(9), 14–25.