- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aspects of British Political History 1815-1914

About this book

Aspects of British History, 1815-1914 addresses the major issues of this much-studied period in a clear and digestible form.

* Introduces a fresh feel to long-studied topics

* Consolidates a grest deal of recent research

* Carefully organised to reflect the way teachers tackle this course

* Written by and experienced and renowned textbook author

* Illustrated with helpful maps and photographs

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Aspects of British Political History 1815-1914 by Stephen J. Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

AN INTRODUCTION TO BRITISH POLITICAL HISTORY 1815–1914

This book is intended to introduce the reader to a range of interpretations on nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British political history. It is designed to act as a basic text for the sixth-form student and to introduce the undergraduate to the wide range of ideas and research relating to the period. I hope it will also capture the imagination of the general reader who likes to go beyond narrative into the realm of debate.

Why political history? And what does it mean? During the 1970s and 1980s there was an outpouring of books specifically on social and economic history, a departure from the older type of text which aimed to cover all areas but within the broad context of political history. To some extent the focus on social and economic history is part of a process of establishing a new balance. In the words of G.R. Elton, the reaction against political history, ‘although often ill-informed and sometimes silly, has its virtues. These arise less from the benefits conferred upon other ways of looking at the past than from the stimulus given to political history to improve itself.’1

Political history now seems to be making a determined comeback, although in a more eclectic guise, covering a wider spectrum and drawing from social, economic and intellectual issues. It is also based more on controversy and debate and less on straight narrative.

Political history may be defined as ‘the study of the organisation and operation of power in past societies’.2 It focuses on people in positions of power and authority; on the impact of this power on various levels of society; on the response of people in power to pressures from below; and on relationships with power bases in other countries. The study of political history fulfils three functions. One is the specific analysis of the acquisition, use and loss of power by individuals, parties and institutions. A second is more generally to provide a meeting point for all other components: social, economic, intellectual, religious – these can all be brought into the arena of political history. But above all, political history offers the greatest potential for controversy and debate. As Hutton maintains, ‘More than any other species of history, it involves the destruction of myths, often carefully conceived and propagated. No other variety of historian experiences to such a constant, and awesome, extent, the responsibility of doing justice to the dead.’3

The rest of this chapter will outline the main political issues covered in this book. It will also introduce a range of general themes which appear in chapters 2–19 and, finally, look at three broad historiographical frameworks for historical analysis.

THE MAIN POLITICAL ISSUES 1815–1914

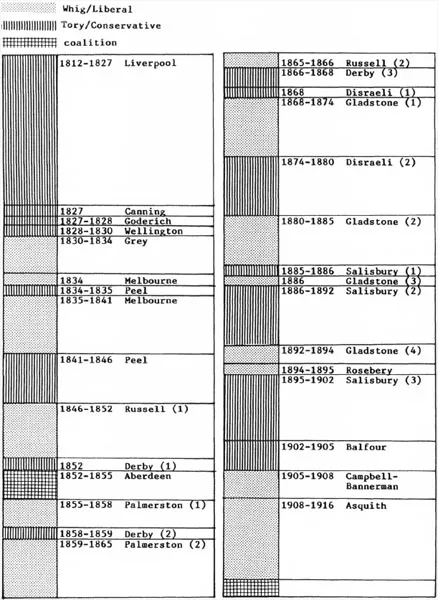

In the first two decades of the nineteenth century Britain was at war with France and confronted by the threat of internal revolution (Chapter 2). This did not, however, materialise – partly because of the relative weakness of those radicals who wanted violent change and partly because of the effective counter-revolutionary measures taken by Lord Liverpool’s government, especially after the end of the French wars in 1815. These, in turn, have been the subject of considerable controversy among historians (Chapter 3). The usual interpretation is that the Tories pursued a reactionary course between 1815 and 1821 – the chief advocates of which were Sidmouth and Castlereagh – while from 1822 more enlightened ministers such as Huskisson, Robinson, Canning and Peel introduced a series of reforms which transformed reaction into a period of ‘liberal Toryism’. A similar divergence has been claimed in Tory foreign policy (Chapter 4) between the measures of Castlereagh and Canning. The former is often strongly associated with the Congress System and with a closer working relationship with the autocratic powers, especially Austria, while Canning is usually held to have followed a more independent line, pursuing British interests which were often in tune with liberal movements in Europe and elsewhere. In both domestic and foreign policy, however, there are strong arguments in favour of an underlying continuity.

It is certainly true that the major change of the first three decades of the nineteenth century was the reform of Parliament by the 1832 Reform Act (Chapter 5), and this was introduced by the Whigs in the teeth of Tory opposition. To some extent, the Whigs saw this as a measure to stave off any future threat of revolution by extending the franchise to the middle classes. Although its political effects were disappointingly limited, the Reform Act did make possible a decade of political domination by the Whigs, which was used to introduce a series of social reforms (Chapter 6). These were motivated partly by pressure groups and partly by a genuine desire by the Whig leaders to improve conditions and bring about a more efficient administration at local level. There were, however, deficiencies in these measures, and the overall reforming programme ran out of steam after 1835; hence in 1841 the Whigs lost a crucial general election to the Tories.

Figure 1 Prime Ministers 1812–1916

Another reason for the political change-over after ten years of Whig power was the revival of the Tories and their transformation into the Conservative party. Largely responsible for this was Sir Robert Peel (Chapter 7) whose reputation rests on two bases: his leadership of the Tory party and his national statesmanship. During the 1830s, the two combined very effectively to make Peel a successful leader of a revived and reinvigorated opposition and, at the same time, a much respected national figure. As Prime Minister between 1841 and 1846 he secured a large measure of economic reform, all very much in the national interest, but with the dwindling enthusiasm of the party. In 1846 he quite deliberately put the national interest first and his battle to secure the repeal of the Corn Laws split his party and brought about his own fall.

Meanwhile, two movements had come into existence to campaign in different ways for quite different objectives. One of these was Chartism (Chapter 8) which aimed to remedy the gaps left by the 1832 Reform Act and achieve universal suffrage. This was justified partly as an inherent political right and partly as a device to ensure the type of parliament which would best be able to secure the extensive social reforms still needed by the working classes. Because of its diverse origins, membership and measures, and because Peel’s economic measures ensured a fairly steady period of economic growth, Chartism never really stood much chance, and the movement folded up in 1848. The other pressure group, the Anti-Corn Law League, was more successful. Set up with the specific purpose of persuading the government to repeal the Corn Laws of 1815 and 1828 (Chapter 9), the League eventually won Peel over to its cause. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 more or less completed Peel’s policy of free trade and probably contributed to the period of agricultural prosperity in the 1850s and 1860s generally known as the ‘golden age of agriculture’. The political impact, however, was the more substantial. The Conservative party split on the issue, the minority joining Peel in the political wilderness. The Peelites, after some years’ existence as a separate party between the Conservatives and the Whigs, eventually joined the latter.

A divided Conservative party gave the Whigs a new lease on life for twenty years after 1846. It was no coincidence that this period was dominated by Lord Palmerston (Chapter 10), probably the most influential politician of the entire century. Usually associated by historians with an aggressive, individualistic and eccentric foreign policy, Palmerston was also a highly successful Home Secretary and, during the years 1855–8 and 1859–65, a popular Prime Minister. Although a traditionalist Whig (despite his Tory origins), Palmerston was instrumental in bringing together a new political coalition of Whigs, radicals and Peelites, which was already during his lifetime being called the Liberal party. Nevertheless, Palmerston was in many ways an obstacle to further political change and progressives welcomed the end of the ‘age of Palmerston’ in 1865.

An immediate development was the further extension of the suffrage in 1867 (Chapter 11). This came about, curiously, as a result of direct competition between the Liberal and Conservative parties to enfranchise the upper levels of the working class. A further instalment occurred with the 1884 Reform Act. These and other measures greatly broadened the base of party politics. The era when the Whigs and Palmerston had dominated now gave way to an alternation of Conservative and Liberal governments led respectively by Disraeli and Gladstone.

Disraeli (Chapter 12) had developed his ideas long before he became prime minister. He had provided the Conservative party with new principles during its period in political exile, although he was unable to give effect to what became known as Disraelian Conservatism until his two ministries of 1867–8 and 1874–80. The reforms of his second government, in particular, showed a combination of progressive aims and pragmatic methods, the precise proportions of which have been the subject of extensive historical debate. The career of his political opponent, Gladstone (Chapter 13), followed a very different course. He, too, had been a member of the Tory party but, unlike Disraeli, had been strongly influenced by Peel’s economic ideas and followed him into political exile before eventually joining the Whigs and assuming the leadership of the new Liberal party after the death of Palmerston. Gladstonian Liberalism showed influences which were both progressive and traditionalist, the uneasy compromise between the two being all too apparent in his domestic policies. But his major priority after 1880 was to settle the Irish problem. His decision to adopt Home Rule may have been based on genuine altruism, or it may have been an attempt to provide the Liberal party with a single, predominant issue to prevent it from becoming divided on the question of the pace of domestic reform, which the more radical members such as Joseph Chamberlain wanted to accelerate. Whatever the truth, Gladstone’s Irish policy split the Liberal party and gravely weakened its electoral performance against the Conservatives between 1885 and 1905.

Meanwhile, British foreign policy had entered a particularly difficult period in the post-Palmerston era (Chapter 14). Gladstone and Disraeli advanced different solutions. The former favoured a revival of multilateral co-operation and respecting the nationalist aspirations of the peoples of the Balkans, now Europe’s major trouble spot; in the process, however, it cannot be claimed that he achieved very much in any specific sense. Disraeli, on the other hand, applied more pragmatic solutions – based on the balance of power – which often cut through the claims for national self-determination and, while solving immediate diplomatic crises, stored up problems for the future. Another development after 1870 was the revival of British imperialism after a comparative lull for three quarters of a century and its focus especially on the continent of Africa (Chapter 15). A variety of reasons have been given for this, including economic rivalries, complications in European diplomacy and the expression of strategic interest. There was also a change in party perceptions: the Conservatives were transformed under Disraeli into the party of Empire. Gladstone, although unenthusiastic in principle, found himself drawn in by local crises. By the end of the century there was, on the one hand, a broad inter-party consensus and, on the other, differences within parties, especially between Liberal Imperialists like Rosebery and little Englanders like Lloyd George.

Dramatic events in the Empire had some impact on the twists and changes in party politics at home. Between 1885 and 1905 the Conservative party dominated the political scene (Chapter 16), winning three out of the four general elections of this period. This was due partly to internal crisis within the Liberal party, especially the split over Home Rule for Ireland, and partly to the growing support for the Conservatives brought about by an effective party organisation and by Lord Salisbury’s leadership. All of this, however, was changed by the traumatic experience of the Boer War, which shattered Conservative dominance and set the charges for the Liberal landslide of 1906.

The next eight years saw a government which was prepared to commit itself to a more intensive programme of legislation than had ever been seen before (Chapter 17). Edwardian Liberalism, under Campbell-Bannerman, Lloyd George and Asquith, aimed at extending the role of the state to secure social reform; this reversed the more traditional emphasis on ‘self-help’ which had been a feature of Gladstonian Liberalism. In the process, Asquith came into direct confrontation with the Conservative-dominated House of Lords. But although the Liberals won this particular contest, the years 1911–14 saw a slowing of their reforming impetus because of their preoccupation with three further crises, which proved even more destabilising: the opposition of the suffragettes, a resurgence of particularly violent industrial unrest, and the revival of the Irish question. By 1914 the future of Liberal power was very much at issue. A potential threat had also emerged from the left – in the form of a new Labour party (Chapter 18). At first Labour MPs had been elected, during the 1870s and 1880s within the Liberal party as so-called ‘Lib-Labs’. In 1900, however, a new party was established, comprising several Labour groups. But although Labour had separated from the Liberal party, having to some extent grown out of it, it was not yet strong enough to compete with it. Hence, in 1903 an electoral pact was drawn up between the two parties, and Labour managed to exert at least some influence on the domestic policies of Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith. By 1914, however, it had become clear that such co-operation was wearing extremely thin. But what could the next stage be? Direct competition would damage both, to the benefit of the Conservatives.

Another theme of the period is the transformation of Britain’s relations with the other powers of Europe between 1895 and 1914 (Chapter 19). During the latter half of the 1890s Britain experienced self-imposed isolation in international diplomacy; although contemporaries referred to this as ‘splendid’ isolation, it is a term which has attracted much controversy. After the turn of the century, this isolation was gradually undermined by a series of agreements although, again, there are disagreements as to whether these meant that Britain was deliberately refocusing her attention away from the Empire and back towards Eur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- 1 An introduction to British political history 1815–1914

- 2 Britain and the threat of revolution 1789–1832

- 3 Tory rule 1812–30

- 4 The foreign policy of Castlereagh and Canning

- 5 The 1832 Reform Act

- 6 Whig reforms in the 1830s

- 7 Sir Robert Peel as party leader and national statesman

- 8 Chartism

- 9 The Corn Laws and their repeal

- 10 Palmerston’s foreign and domestic policies

- 11 Parliamentary reform: 1867 and beyond

- 12 Disraeli and the Conservative party

- 13 Gladstone, Liberalism and Ireland

- 14 The foreign policy of Disraeli and Gladstone

- 15 British imperialism and the Scramble for Africa

- 16 Conservative ascendancy 1885–1905

- 17 Liberal domestic policies 1905–14

- 18 The rise of the Labour party before 1914

- 19 From splendid isolation to war: British foreign policy 1895–1914

- 20 Government policy and the economy 1815–1914

- 21 Government policy towards social problems 1815–1914

- 22 Britain and Ireland 1800–1921

- 23 Primary sources for British political history 1815–1914

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index