The history of the migration of footballers to Europe and within this continent is not something new (Lanfranchi and Taylor, 2001; Taylor, 2006). From the outset, the worldwide diffusion of football has been the work of a transnational elite expatriated within the context of the expansion of capitalism (Lanfranchi, 2002) and the development of a ‘world economy’ (Wallerstein, 2006). Quotas limiting the presence of foreign players were first introduced in the 1920s as a result of the interwar geopolitical tensions (Poli, 2006a). For several decades, legal constraints have drastically limited expatriate presence in European clubs. Up until 1995, the percentage of expatriates in the five major European leagues1 had never risen above 10 per cent (Poli and Ravanel, 2009).

At the end of the 1980s, regulations were eased and foreign presence started to increase. With the advent of the ‘Bosman’ law, decreed in 1995 by the European Court of Justice (Dubey, 2000), this progression increased markedly. In obliging the federation of EU countries to review their regulations and to free up the circulation of EU players, this ruling has allowed clubs to take advantage of new recruitment possibilities. In just five seasons, between 1995 and 2000, the percentage of expatriates taking part in the big-five leagues has increased from 18.6 per cent to 35.6 per cent. While it has slowed down thereafter, this augmentation has continued without interruption to the present day. During the season 2008/2009, the percentage of expatriates in the five top European leagues has reached a record level of 42.6 per cent (Poli et al., 2009).

The increase of international flows following the liberalisation of the football transfer market takes place as much between EU member countries as it does between non-EU ones. Between 1995 and 2005, the percentage of extra European players in the five principal leagues has gone up from 6.4 per cent to 19.2 per cent. During the 2005/2006 season, extra-European footballers made up half of the total of expatriates, instead of one-third ten seasons previously. The augmentation of non-EU players is due to the fact that they benefit from the places left vacant by citizens of countries that are no longer taken into account by quotas. From this point of view, the ‘Bosman’ ruling has particularly favoured Latin American footballers, a majority of whom are also in possession of EU passports (especially Spanish, Italian or Portuguese).

The strategies for global recruitment elaborated by European clubs reflect the development of a new international division of labour in the ‘production’ of footballers. Powerful transnational transfer networks made up of players’ agents, private investors, club managers and trainers henceforth take charge of the setting up of the relation between supply and demand on a global level (Poli, 2007a, 2008). With this in mind, certain countries such as Brazil and Nigeria have become progressively specialised in the training of footballers and their exportation to Europe or Asia, continents where football generates higher revenues. The increase in international flows and the development of new recruitment strategies form part of the framework of the globalisation of the labour market of sporting personnel (Bale and Maguire, 1994a; Maguire and Stead, 1998; Poli and Ravenel, 2005b). Considered from a transformationist’s perspective (Held et al., 1999), this process implies the functional integration of spaces on a vast geographical scale (Dicken, 2007).

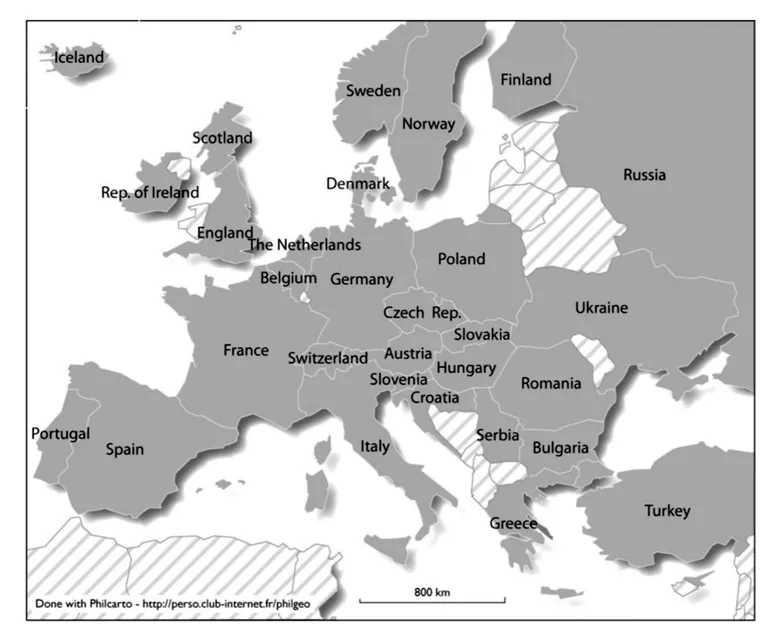

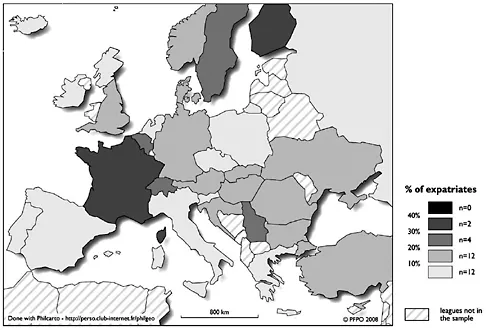

Today Africa and Latin America constitute preferred recruitment areas for European clubs. The objective of this article is to comparatively analyse the presence of players of these two zones of origin within the principal European championships so as to bring out similarities and differences. The data on which we base our analysis comes from a census carried out between September and October 2008 by the Professional Football Players’ Observatory (PFPO)2 based on a sample of 30 top division leagues in countries belonging to Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) (Figure 1.1). This census, undertaken by cross-referencing the data from different sources (official club websites, federations and electronic databases), has allowed the enumeration of 11,015 active footballers3 including information on their origin as well as certain characteristics such as position, height or age. Our goal being to measure the international flows directly linked to football, independently of the nationality of players, the notion of expatriate is preferred to that of foreigner. An expatriate is a footballer playing outside of the country where he grew up in, from where he departed following recruitment by a club abroad.

Spatial logics of international recruitment and diversification of migration routes

In total, the 456 European clubs taken into account by the census employed 3,923 expatriates or 35.6 per cent of the total number of footballers. The Latin American players, numbering 979, represented a quarter of expatriates (25.0 per cent). Less numerous, players recruited in Africa (531) constituted 13.5 per cent of the total number of expatriate footballers (Table 1.1).

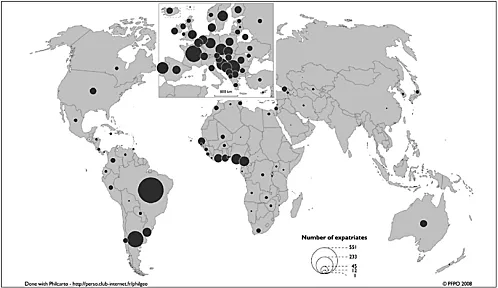

It is interesting to note that, from a geographical point of view, the ‘production’ of players in Africa is concentrated primarily in the western part of the continent (Figure 1.2). On a national level, Brazil is by far the country that exports the greatest number of players to Europe. Numbering 551, Brazilians make up the biggest contingent of expatriate players. Brazil’s role in the training and exportation of players is not limited to Europe. In 2004 alone, the Brazilian Football Confederation recorded the departure of 846 players seeking to capitalise on their talent worldwide, 60 per cent of them elsewhere than in Europe (Théry, 2006).

Table 1.1 Number and percentage of expatriate players by zone of origin

While numerous European countries also export players to other European nations (particularly France), the flows from Asia and North America remain limited. The worldwide geography of football differs in this way from that of international trade where Asia and North America occupy a central position. Conversely, Africa and Latin America, two continents somewhat on the fringes of

major international commercial flows, play an essential role in the worldwide market for footballers.

The process of globalisation is often understood from an aspatial perspective (Massey, 2005) that deems that there are no longer any borders and that the world has become a homogenous space of action for all individuals. This vision had been strongly criticised in that it does not take into account the permanence of social factors linked to history of relations between territories in the geographical configuration of flows. Incidentally, Meyer proposes a connectionist approach and reminds us that ‘people are not moving in a vacuum between supply and demand. They are actors whose movements, constructed through and resulting from collective action, can be traced and described accurately instead of being left to external and elusive macro-determinations.’ Accordingly, for Meyer, migrants are not made up of ‘a volatile population of separate units in a fluid environment but rather a set of connective entities that are always evolving through networks, along sticky branches’ (2001, p. 96).

The importance of networks in the migration of sportsmen has also been highlighted by Maguire and Pearton, for whom

In the case of English football, McGovern (2002) has also insisted upon the permanence of spatial logics inherited from the history of territories in the structuring of flows. In a more recent article, Maguire and Elliott (2008) underline the importance of going beyond the sole analysis of the motivations of sporting migrants, so as to also study the structure and mechanisms of recruitment.

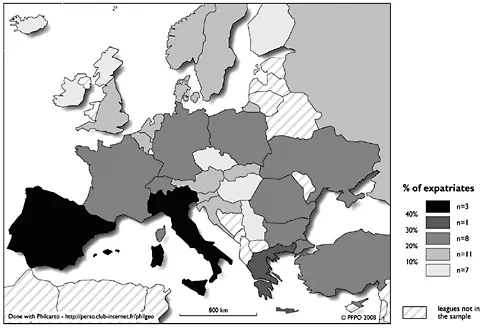

On the basis of these observations, it is not surprising to notice that the presence of Latin Americans among the expatriates in the 30 leagues is quite contrasted. It is particularly strong in Portugal (79.6 per cent), Italy (51.0 per cent) and Spain (47.8 per cent), countries with which relations are historically important. In nine other leagues, Latin American footballers make up more than one-fifth of the expatriates. In contrast, championships such as the Scottish (2.5 per cent) or Irish (1.5 per cent) ones hardly have any. Generally speaking, the percentage of Latin American players decreases relative to a South–North gradient (Figure 1.3).

Though the ratio of players having grown up in Africa also varies according to country, the differences are less important. The country in which they are the most present among expatriates is France (37.0 per cent). Contrary to Latin American players, the championships of Northern Europe such as Finland (35.9 per cent), Sweden (23.5 per cent) or Norway (18.7 per cent) figure among those where the proportion of African footballers is higher than the European average. African players are also relatively numerous in Central Europe (Switzerland,

Belgium) and in certain Eastern European leagues (Serbia, Hungary, Turkey, Romania, Ukraine). In contrast, no African footballer is playing in Iceland. Among the countries where Africans are not numerous we also find Scotland (3.3 per cent) and Ireland (3.0 per cent), which have already stood out in the case of Latin American footballers (Figure 1.4).

The analysis of the distribution of Latin American and African players brings to light a double logic. On the one hand, with the exception of the English championship, where international recruitment is much more orientated towards neighbouring countries, the old colonial powers such as France, Portugal and Spain continue to amply draw from the reservoir of talent of the previously colonised countries (Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Senegal, Mali, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay notably). On the other hand, the migratory routes tend to diversify, which reflects the functional integration of spaces taking place in the context of the globalisation of the footballers’ labour market.

This confirms the analysis carried out by Maguire and Stead (1998a), who have highlighted that ‘sports labour migration is, in part, a reflection of pre-existing social, political and economic power arrangements in sport. It can also be an indicator of, and a factor in, bringing about change’ (p. 60). The tension between continuity and change has been expressed by these authors in terms of ‘centrifugal and centripetal forces’ (p. 72), which are simultaneously at work in the context of the international labour market of footballers.

The diachronic analysis of the concentration of expatriate players according to their origin allows us to measure the relative weight of these two types

of forces in the last few years. The index of dissimilarity4 is an index of segregation that has long been used in the social sciences (Rhein, 1994; Apparicio, 2000; Voas and Williamson, 2000). It measures the proportion of a given population that must change spatial unit so that its distribution between the different units is identical to that of another population. When applied to the case of footballers, this index permits the comparison of the distribution of players having a certain origin in comparison to other expatriates. If all the expatriate players coming from a given country take part in the same championship and if the latter only has players from this origin, the dissimilarity is maximal (index value of 1). Inversely, if players of the same origin are distributed exactly in the same manner between the different championships as those of other origins, the dissimilarity is minimal (index value of 0).

In 2008, Africa constituted the zone of origin for which the distribution within the 30 championships was the most balanced (0.28). The degree of specialisation of the distribution of Latin Americans (0.35) is similar to that of expatriates from Western Europe (0.36) and those from the category ‘Others’ (0.36), which includes North American, Asian and Oceanic footballers. Eastern Europeans, particularly over-represented in the east of the continent due to a logic of proximity, are those who show the greatest dissimilarity (0.42) (Table 1.2).

A comparison with the situation in the 30 leagues in 2002/2003 indicates a reduction in the specificity of the distribution of expatriates according to origin. This result confirms the existence of a process of diversification of migration

Table 1.2 Change in the index of dissimilarity according to zone of origin (2002/2003–2008/2009)

Table 1.3 Change in the index of dissimilarity according to nationality (2002/2003–2008/2009)

channels. With the exception of the category ‘Others’, of which the numbers are few (123 players in 2003), all the zones of origin have seen their index of dissimilarity decrease in 2008. The drop is particularly noticeable for Africans (0.09), even though they already had the least specific distribution in 2003 (0.37). By comparison, the dissimilarity of Latin Americans dropped only half as quickly (0.04).

While the differences in t...