eBook - ePub

Leading and Managing Teaching Assistants

A Practical Guide for School Leaders, Managers, Teachers and Higher-Level Teaching Assistants

- 226 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Leading and Managing Teaching Assistants

A Practical Guide for School Leaders, Managers, Teachers and Higher-Level Teaching Assistants

About this book

There are more than 200,000 teaching assistants(TAs) in the UK. This comprehensive, practical book deals with how to make use of them effectively. Written by a recognised authority on TAs the book investigates

- the roles of leadership and management

- the various roles of TAs and what distinguishes them from other support staff

- the whole-school learning environment

- Auditing the needs of the school and the needs of the TAs

- good practice in appointing and developing TAs – technicalities, examples and proforma.

- using a TA in the classroom - guidance for teachers

- leading a team of TAs.

This supportive and stimulating book is complemented with practical and effective strategies for managing TAs. TAs can contribute to higher standards for pupils, better curriculum delivery, improved work-life balance and effectiveness for teachers and support for whole school policies.

Including examples of good practice, real-life accounts, research evidence, sources of help and suggestions for further reading, this book provides all the guidance a manager will need to help them make the best use of their TAs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Leading and Managing Teaching Assistants by Anne Watkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Teachers or instructors of children and young people have always had their assistants. The Greeks, teaching in the open air did. The Victorians are well documented for using the older pupils as pupil teachers. During the 1960s, the teacher unions were struggling, first to ensure that all teachers were qualified, and then to gain graduate status for qualified teachers. Largely because of this, ‘unqualified’ ancillaries were derided as usurping the teachers’ place. However, many schools employed welfare assistants to help with first aid, caring tasks and menial classroom tasks such as paper cutting or paint pot washing. The early 1990s saw the beginnings of serious research into staff supporting in the classroom, and women were seen as a possible ‘Mum’s army’ to support those teaching children under eight years old. The first qualifications for assistants started to appear, although many concentrated on provisions in the early years of education.

Following the general election of 1997, government initiatives have ensured an exponential growth of the number of teaching assistants (TAs) in schools. By 2000 a five-pronged strategy was developed with money and projects behind their words:

- recruitment money was distributed to schools via Local Education Authorities (LEAs);

- induction materials were prepared to be rolled out to school via the LEAs;

- a career ladder for TAs was developed with the writing of National Occupational Standards (NOS) at levels 2 and 3 leading to nationally recognised qualifications;

- advice on management was published which is still a seminal text recommended by the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) and the Training and Development Agency (TDA); and

- pathways to teaching were made easier with workplace routes.

There must now be well over 200,000 people employed in this capacity, if government statistics quote 150,000+ full-time equivalents (FTEs). There are very few schools without TAs yet few TAs have full-time contracts. More people cannot just be tacked on to an existing group without consideration of their conditions of service and the impact on the leadership and management of the school. It was recognised some years ago that: ‘The substantial increase in the number of teaching assistants in schools and the corresponding increase in our expectations of what they do, not surprisingly has made the management of teaching assistants more complex’ (Ofsted 2002: 18). Even now some TAs are still not fully included into whole-school activities

Since local management of schools was introduced in the late 1980s, heads have been able to staff their schools according to need rather than take the allocations handed to them by their local authority (LA). Many schools have stayed with the traditional one teacher per class of 30 in primary, and one teacher for 20 to 30 in secondary, with fewer in practical classes, specialised sixth form or special educational needs (SEN) groupings.

With the establishment of the national curriculum (NC), there has been even more emphasis on year grouping in primary schools; nationally produced schemes of work reinforce this. The Literacy and Numeracy Strategies (LNS) of the last ten years have reinforced this structure bringing an almost wholesale return to class teaching in primary schools. Parental pressure also supports the concept and seems to influence headteachers and governors more in their staffing structure than any other issue. The NC and its associated testing culture and published league tables has even brought about the demise of the middle school systems in some authorities. It is believed that this year grouping structure has raised standards. Class-based staffing and the consequent financing of such a straitjacketing concept has dominated many schools, to the detriment of allowing pupil needs, people potential and initiative possibilities to be thought through effectively.

The LNS undoubtedly brought about needed changes in lesson planning and execution for some teachers and a considerable increase in the use of TAs for curriculum work as distinct from their SEN, welfare and more menial roles. This was not only to support individuals or small groups with extraction or catch-up agendas, but also to support groups in whole classes.

The major initiative that has affected the employment of TAs in the last 20 years, one that has affected secondary schools and primary in equal measure, is that of inclusion. This has also accelerated in the last ten years.

Complaints about teacher workload, reported in some depth in a Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC) report (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2001), the introduction of the LNS dependent on additional adult support and an increasing emphasis on the inclusion of pupils with SEN in mainstream schools led to the ideas of Workforce Remodelling (WR) introduced to schools in 2003. WR was an attempt to encourage schools to think more innovatively about their staff, especially their support staff, in managing the needs of the curriculum and pupils and coping with the ever increasing initiatives. The proposals were outlined in documents headed ‘Time for standards: reforming the school workforce’ (DfES 2002). The unions, with one exception, signed up to an agreement for implementation (ATL et al. 2003). Part of the agenda of the WR was to utilise staff most effectively to increase standards. A lot of guidance was published to support schools, a three-year funded project with local and national advisers accompanied the proposals.

Schools have been encouraged to consider the employment of support staff by looking at their staffing structure and management as a more holistic exercise. Historically, most schools had used rather ad hoc employment strategies to appoint assistants. The idea was to take a fresh look at the needs of the school, the pupils, the curriculum and their local circumstances to decide what combination of teachers and support staff best fitted these needs. The TDA has become the disseminator of all the WR material since the project’s completion. Their website states:

The remodelling change process enables and encourages schools and their partners to:

- identify and agree where change is necessary

- facilitate a vision of the future shared across the whole-school and stakeholder communities

- collaborate internally and externally, with other schools, organisations and agencies, in an effective and productive way

- create and implement plans for ‘tailored change in an atmosphere of consensus

- embed an inclusive and proactive culture of long term progress, and improve standards for staff, stakeholders and pupils.

(TDA 2007b)

A new status, that of higher level TAs (HLTAs) has also been introduced to enable experienced TAs, who did not wish to be teachers, yet are of high calibre, to be recognised. Foundation degrees, work-based routes to teaching and apprenticeships have all added to a scene of complex employment structure possibilities for TAs. A national pay and conditions structure for TAs is at last being considered (TES 2007a). The TDA now has overall responsibility for TA matters, enabling joined-up thinking to take place at government level. Previously, the Teacher Training Agency (TTA) was responsible for teachers and the Employers Organisation (EO) for support staff as local government employees.

Three years later, when earmarked standards funds have been exhausted for WR, it is suggested that whole-school budgets should be sufficient to enable managers to fund staffing according to their local needs, not those of government or historical perceptions. However, this is not so evident at school level. Also, employment of TAs is not just a matter of structure. It is evident from personal observation, discussion with advisers across the country and assessing and moderating the HLTA applications, that there is still considerable misunderstanding of the potential of TAs, their best use and deployment and how the day-to-day matters of school life can best be facilitated for the good of the pupils and the TAs themselves. TAs of all descriptions and levels raise serious issues, most of which could be resolved by better management practice, whole-school vision and a sense of collegiate responsibility for the learning, health and welfare of the pupils within a school.

There are further government initiatives coming on stream which will influence schools’ use of TAs. The Every Child Matters (ECM) agenda permeates everything from the schools’ inspection framework to all the local agencies concerned with children. Extended schools, where school buildings and communities encompass far more than educating children from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., personalised learning, assessment for learning, are just a few of the buzzwords echoing round staffrooms along with major changes in the 14 to 19 agenda and the imminent revision of the NC.

Maggie Miller’s story exemplifies how the changes in the national scene have brought about change in her personal life and the potential growth of TAs’ usefulness given supportive management.

_______________

School example

Maggie left school with five ‘O’ levels and an ‘OA’ level and went to work in a bank, then a computer firm and then for her husband’s firm, only leaving at the birth of her son. She then took what is a common route, first becoming a school volunteer in her son’s school, later becoming employed as a special needs welfare helper. She then went back to college, and after teaching adults basic literacy skills for a while, went back to a part-time post in a junior school. She is now the TA team coordinator, leading a team of 11 TAs, as well as being the behaviour support coordinator. She liaises with both the head and the SEN coordinator (SENCO), and also with teachers, social workers and parents, and runs weekly meetings for the TAs. Her team leadership role includes performance management and her now HLTA role includes covering for teacher absence and planning, preparation and assessment (PPA) time. She undertakes other school administrative tasks and a lunchtime information and communication technology (ICT) club. She has her National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) assessor’s award and so can assess in-house TAs at level 3 NVQ where they wish to achieve it.

A further Cambridge University course in counselling skills has brought her in touch with a much wider group of educationalists. She now has the expertise and confidence to address conferences and run workshops. She has developed a county-wide role as TA consultant for Hertfordshire LA, including profiling the training needs of TAs using the NAPTA/Pearson Educational tools.

_______________

The potential of appropriate leadership and management

TAs’ development is a process during which adults who have outward-going, caring personalities, a commitment to education and are prepared to develop and undergo training of a variety of kinds can provide responsive, sensitive and knowledgeable aides to the teaching and learning process. WR was an opportunity to rethink, but it also opened up further problems for leaders and managers to deal with, such as the support that TAs need to fulfil a larger role. Also, what teachers might need to work effectively with the additional adults. The issue of dealing with yet more staff was not new.

Why bother? In this instance, we believe there are good reasons, both educational and financial for bothering. We believe it is time to look again at the traditional patterns of staffing in schools. Over the years, teachers’ roles have become unnecessarily rigid… We think there is much scope yet to be explored and we are sure that there will be benefits not only to associate staff and their teacher colleagues able to focus more properly on pedagogy, but also to individual pupils and to the school as a whole. It is right they should be staffed by colleagues from a variety of backgrounds, bringing appropriate skills to the corporate life of the institution.

(Mortimore et al. 1994: 222)

It is a common experience with training institutions and LAs that unfunded courses for senior staff about managing TAs collapse from lack of support. Whether this is because of other priorities or a sense that managers know all they need to know is impossible to say. If you have read this far, you are clearly not one of those who feel they know all about the subject, and you are willing to think about your practice. Managers and leaders are not just ‘those at the top’. Teachers lead and manage TAs, but still have very little guidance despite this becoming part of the standards for Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) in 2001. With the acceptance of HLTA status in schools, job evaluation and various grades with concomitant job descriptions (JDs), TAs themselves have also become managers and leaders of teams of TAs.

THINKING POINTS

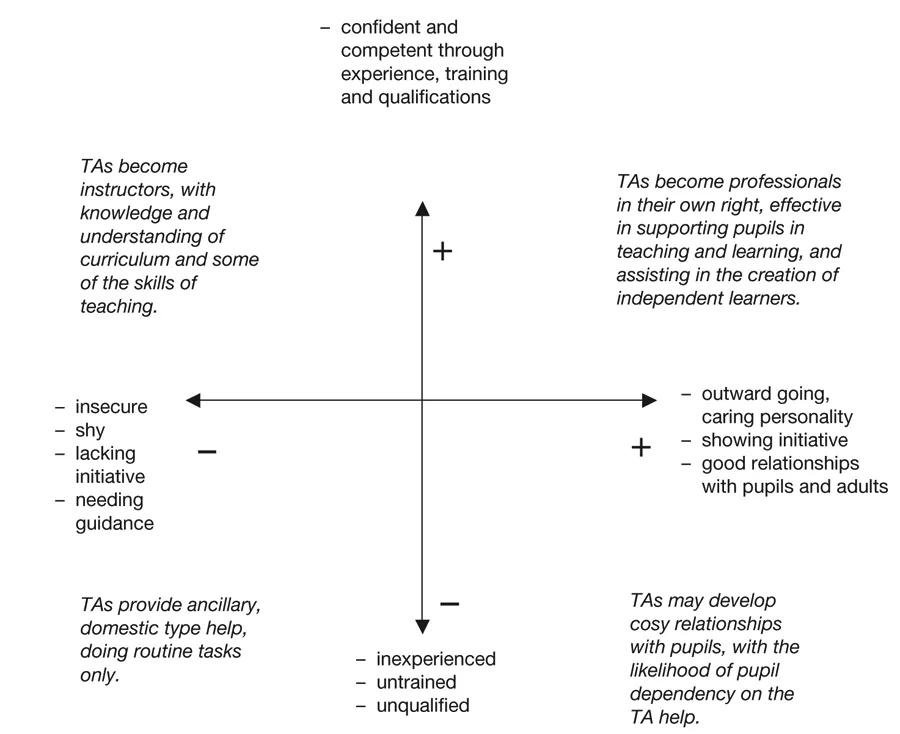

How well do you know your team of TAs? Figure 1.1 shows how training and personality can combine to produce a professional TA. Consider your TA team and try to place them on the diagram as a series of crosses. Hopefully they are well into the upper right hand quartile?

Figure 1.1 Looking at the TAs by themselves (Watkinson 2003: 166)

The usefulness of a TA is only as good as their management and deployment. It is up to you, the leaders and managers to maximise the use you make of the skills, knowledge and understanding developed by TAs that will create support for pupils, teachers and the school to provide a consistent high standard of professional practice and improve standards for staff and pupils. Whatever your rationale for employing them, you want them, as with any resource, to be effective. A simple list of factors for effective working by teaching assistants was given in Lee’s survey in 2002. The presence of this book seems to indicate that there is still a need for leaders and managers to consider some of these. To start you off you could check what you have in place against this list:

- clarity of role

- accurate and updated job description

- thorough induction and support structures

- clear line management ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Leadership and management

- 3 Managing people

- 4 Why employ TAs?

- 5 The whole-school learning environment

- 6 Looking at the needs of the school and of the TAs

- 7 Performance review

- 8 Professional development for and of TAs

- 9 Good practice in appointing and developing TAs

- 10 Empowering TAs to support the learning process

- 11 Concluding thoughts

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Bibliography