![]()

1 | From Orderly to Complexity Science |

The end of our foundation is the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things: and the enlarging of the bounds of human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible.

(Francis Bacon, The New Atlantis 1627)

What is the complexity paradigm? How and when did it emerge? Is it a hot new academic fad like globalisation or the end of history, or is it something more profound? To begin to answer these questions we need to jump back a few centuries and briefly discuss the emergence of what is commonly labelled the ‘Newtonian’ or ‘linear’ paradigm. For reasons that will become clear, we have called it ‘the paradigm of order’.

The Paradigm of Order

Although it has been said thousands of times before, it bears repeating that the Enlightenment was an astounding time for Europe. Relatively stagnant and weak and intellectually repressed by the Church during the so-called Dark Ages, intellectual energies released by the Renaissance came to fruition in the Enlightenment. During this time, Europe was reborn and became the centre of an intellectual, technical and economic transformation. It had an enormous impact on the way life is viewed at all levels from the mundane to the profound. Science was liberated from centuries of control by religious stipulations and blind trust in ancient philosophies. Rene Descartes (1596–1650) and, slightly later, Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727) set the scene. The former advocated rationalism while the latter unearthed a wondrous collection of fundamental physical laws. A flood of other discoveries in diverse fields such as magnetism, electricity, astronomy and chemistry soon followed, injecting a heightened sense of confidence in the power of reason to tackle any situation. The growing sense of human achievement led the famous author and scientist Alexander Pope to poeticise, ‘Nature, and Nature’s laws lay hid in night. God said Let Newton be! And all was light’.1 Later, the eighteenth century French scientist and author of Celestial Mechanics, Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749–1827), carried the underlying determinism of the Newtonian framework to its logical conclusion by arguing that ‘if at one time, we knew the positions and motion of all the particles in the universe, then we could calculate their behaviour at any other time, in the past or future.’

The subsequent phenomenal success of the industrial revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which was based on this new scientific approach, heightened confidence in the power of human reason to tackle any physical situation. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century many scientists believed that few surprises remained to be discovered. For the American Nobel Laureate, Albert Michelson (1852–1931), ‘the future truths of Physical Science are to be looked for in the sixth place of decimals’ (Horgan 1996: 19),2 implying that physicists were now only filling in the small cracks in human knowledge. More fundamentally, the assumption and expectation was that over time the orderly nature of all phenomena would eventually be revealed to the human mind. Science became the search for hidden order. The universe and everything in it is a magnificent clockwork mechanism.

By and large, that vision of the universe survived well into the twentieth century. In 1996 John Horgan, a senior writer at Scientific American, published a bestselling book entitled The End of Science which argued that since science was linear and all the major discoveries had been made, then real science had come to an end. All that was left was ‘ironic science’ which ‘does not make any significant contributions to knowledge itself. Ironic science is thus less akin to science in the traditional sense than to literary criticism – or to philosophy’ (Horgan 1996: 31).

Similarly, the eminent biologist and Pulitzer prize winner, Edward O. Wilson argued in his bestselling book Consilience (1998) that all science should be unified in a fundamentally linear framework based on physics:

The central idea of the consilience world view is that all tangible phenomena, from the birth of stars to the workings of social institutions, are based on material processes that are ultimately reducible, however long and tortuous the sequences, to the laws of physics.

(Wilson 1998: 291)

The orderly view of the world prospered not only in sciences, but in the fundamental nature of Western social and political life.

To simplify drastically, the paradigm of order was founded on four golden rules:

- Order: given causes lead to known effects at all times and places.

- Reductionism: the behaviour of a system could be understood, clockwork fashion, by observing the behaviour of its parts. There are no hidden surprises; the whole is the sum of the parts, no more and no less.

- Predictability: once global behaviour is defined, the future course of events could be predicted by application of the appropriate inputs to the model.

- Determinism: processes flow along orderly and predictable paths that have clear beginnings and rational ends.

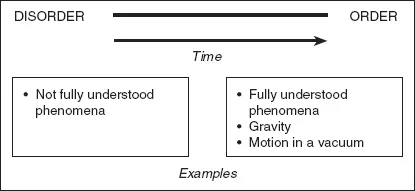

Figure 1.1 Phenomena in the paradigm of order.

From these golden rules a simple picture of reality emerged.

- Over time as human knowledge increases, phenomena will shift from the disorderly to the orderly side.

- Knowledge equals order. Hence, greater knowledge equals greater order.

- With greater knowledge/order humans can increasingly predict and control more and more phenomena, including human phenomena and systems.

- There is an endpoint to phenomena and hence knowledge.

The orderly paradigm worked remarkably well and was conspicuous by incredible leaps in technological, scientific and industrial achievements. Science became orderly and hierarchical with clear divisions that manifested themselves in the departmentalised evolution of modern universities. Not surprisingly, success in these areas had a profound effect on attitudes in all sectors of human activity, spreading well beyond the disciplines covered by the original discoveries.

Spreading Ripples of Doubt

Certainty and predictability for all, the hallmarks of an orderly frame of mind, were too good to last. Fissures had existed for some time, even Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens in the seventeenth century couldn’t agree on something as fundamental as the nature of light (whether it is a particle or a wave). These difficulties bubbled under the surface of acceptable scientific discourse and the expanding university arenas. They were often seen as unimportant phenomena that would be resolved by the next wave of emerging fundamental laws. However, by the early twentieth century they could no longer be ignored. The physicist Henri Poincaré (1854–1912) was one of the first to voice disquiet about some contemporary scientific beliefs. He advanced ideas that predated chaos theory by some seventy years (Coveney and Highfield 1995: 169). Later, Einstein’s (1879–1955) theory of relativity, Neils Bohr’s (1885–1962) contribution to quantum mechanics, Erwin Schrödinger’s (1887–1961) quantum measurement problem, Werner Heisenberg’s (1901–76) Uncertainty Principle and Paul A.M. Dirac’s (1902–84) work on quantum field theory all played a decisive role in pushing conventional wisdom beyond the Newtonian limits that had enclosed it centuries before. These scientists, all Nobel Laureates, set in motion a process that eventually transformed attitudes in many other disciplines.3

The new discoveries did not disprove Newton. Essentially, they revealed that not all phenomena were orderly, reducible, predictable and/or deterministic. For example, no matter how hard classical physicists tried they could not fit the dualistic nature of light as both a wave and a particle into the orderly classical system. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, which shows that one can either know the momentum or position of a sub-atomic particle, but not both at the same time, presents an obvious problem for the orderly paradigm. Or, the paradox of Schrödinger’s Cat experiment, which demonstrated the distinctive nature of quantum probability and again broke the fundamental boundaries of the former order. What this meant was that even at the most fundamental level some phenomena do conform to the classical framework and others do not. With this, the boundaries of the classical paradigm were cast asunder. Gravity continued to function and linear mechanics continued to work, but it could no longer claim to be universally applicable to all physical phenomena. It had to live alongside phenomena and theories that were essentially probabilistic. They did not conform to the four golden rules associated with linearity: order, reductionism, predictability and determinism. Causes and effects are not linked, the whole is not simply the sum of the parts; emergent properties often appear seemingly out of the blue, taking the system apart does not reveal much about its global behaviour, and the related processes do not steer the systems to inevitable and distinct ends.

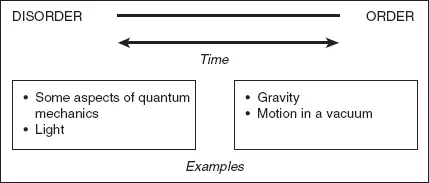

Given these non-linear phenomena and non-adherence to the golden rules of order, new expectations were necessary for this expanding paradigm:

- Over time human knowledge may increase, but phenomena will not necessarily shift from the disorderly to the orderly.

- Knowledge does not always equal order. Greater knowledge may mean the increasing recognition of the limits of order/knowledge.

- Greater knowledge does not necessarily impart greater prediction and control. Greater knowledge may indicate increasing limitations to prediction and control.

- There is no universal structure/endpoint to phenomena/knowledge.

Figure 1.2 Phenomena in the paradigm disorder and order.

It is important to note that the shift in scientific analysis from utter certainty to considerations of probability was not accepted lightly. Schrödinger had originally designed his cat experiment as a way of eliminating the duality problem! The sea change radiated slowly outwards from quantum mechanics’ domain of subatomic particles. Naturally, there was a wide schism between the exclusive niches occupied by leading particle physicists and mathematicians on the one hand, and the rest of the scientific community on the other. High specialisation meant that even scholars involved in the same discipline were not immediately aware of discoveries being made by their colleagues. Moreover, the language of science itself became almost unintelligible beyond a select circle of specialists. In any case, their intriguing speculations were not thought at first to be of everyday concern. Nevertheless, uncertainty was eventually recognised as an inevitable feature of some situations. In effect, the envelope of orderly science was expanded to embrace complex phenomena, also known as complex systems, to those already in place.

Complex Systems in the Physical World

Once the door was open to probability and uncertainty, a new wave of scientists began studying phenomena that had previously been ignored or considered secondary or uninteresting, aspects that the Nobel prize winner Ernst Rutherford disparagingly called ‘stamp-collecting’ activities (Briks 1962: 108).4 Weather patterns, fluid dynamics and Boolean networks were just three of the areas that saw the growing acceptance of non-linear complex phenomena and systems. For example, one of the earliest people to conceptualise and model a complex system was an American meteorologist, Edward Lorenz (see Gleick 1987). Lorenz developed a computer programme for modelling weather systems in 1961. However, to his dismay due to a slight discrepancy in his initial programme, the programme produced wildly divergent patterns. How was this possible? From an orderly framework, small differences in initial conditions should only lead to small differences in outcomes. But, in Lorenz’s programme, small discrepancies experienced positive feedback and reinforced themselves in chaotic ways producing radically divergent outcomes. Lorenz called this the ‘butterfly effect’, arguing that given the appropriate circumstances a butterfly flapping its wings in China could eventually lead to a tornado in the USA. Cause did not lead to effec...