![]()

1

Dynamical Systems:

It is about Time!

Bennett I. Bertenthal

University of Chicago

What is a dynamical system? In simple terms, it is a means to describe the temporal unfolding of a system. It is concerned with two fundamental concepts, change and time. For example, a psychological process, such as memory or cognitive development, unfolds by progressing through a series of discrete states that occur over time. Every dynamical model has time as a variable, although it is often represented implicitly (Ward, 2002). In more formal terms, a simple dynamical model is a differential equation, such as the following simple linear one dx/dt = at. A somewhat more complex model involves feedback, dx/dt = ax − bx,2 which provides a mechanism by which the system can self–organize. (In this latter example, −bx2 is a negative term and will decrease the rate of change of x at an accelerating rate as x gets larger.) Mathematics is the language of dynamical systems, which is both a strength and a weakness for the psychological sciences.

Although the study of dynamical systems has had a long and venerable history in the physical sciences (Abraham, Abraham, & Shaw, 1992), it has yet to have a major impact in the psychological sciences. This seems somewhat paradoxical given that psychologists are interested in a wide range of phenomena that change over time, including learning, memory, thinking, and development. How can we explain this failure to explicitly incorporate dynamical systems in the study of these phenomena? The crux of the problem is that dynamical systems theory is couched in mathematical terms. This is true for both the conceptual foundations as well as for the analytic techniques. Accordingly, many of the key concepts are inaccessible to the average psychological scientist, and the same is true for quantitative techniques that have been proposed specifically for addressing psychological questions. One of the principle goals of this book is to familiarize readers with these techniques, and hopefully present them in a manner that will make them accessible to a much larger contingent of psychological researchers.

Given the theme of this book, you may be wondering why I was given the assignment of writing this introductory chapter. I am not an expert in dynamical modeling, nor do I have a great deal of experience with modeling in general. I am not a quantitative psychologist, and I have a limited background with differential and difference equations, which are the staples of dynamical systems. Nevertheless, my interests in the development of behavior have instilled in me an appreciation for the importance of studying the emergence of new behaviors over time and the myriad of factors that contribute to these changes. These changes over time, which involve the formation of new patterns, represent one of the central themes in dynamical systems. I have also been fortunate to work with a number of graduate and postdoctoral students who helped me navigate through the jargon and the mathematics to learn about the basic concepts and analytic tools. This knowledge has led me to a much more sophisticated appreciation of the dynamics of behavior, and has provisioned me with new tools for studying behavior and development. In this chapter, I provide a very selective review of some key concepts in dynamical systems that help to broaden our understanding of human behavior. This review is organized into four sections: Statical versus dynamical models, Time scales of human behavior, Nonlinear analyses, and Behavioral variability.

1.1 | STATICAL VERSUS DYNAMICAL MODELS |

By definition, motion perception involves a dynamical system in which the state of the stimulus display is continuously changing. Paradoxically, it was commonly believed for much of the 20th century that that motion or event perception was processed as a series of static images. Once these images were sequentially encoded, an inferential process was applied to decide whether these images represented the same object moving in space and time or whether these images corresponded to different objects in different locations. The problem with this interpretation is that it began with a statical model of visual perception, which was unable to explain how the perception of structure–from–motion was not present in any static image, but emerged only from structural changes that were perceived over time.

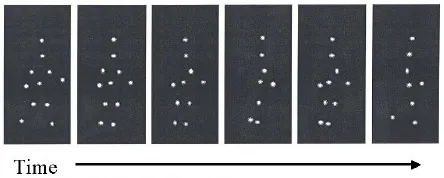

A compelling example of this effect was first demonstrated by Johansson (1973) who showed moving point–light displays of people walking to observers. These displays consisted of 13 point–lights corresponding to the head, shoulders, elbows, arms, hips, knees, and ankles of a person walking. When these displays are shown as a static image, they are typically not recognized or recognized very slowly as a person walking. By contrast, moving versions of these displays are recognized quickly and unequivocably as a person walking. Figure 1.1 simulates this effect by showing a series of six sequential frames from a moving point–light display of a person walking. The point to emphasize is that the structure of this stimulus display is not present in any single image, but rather is an emergent property of the transforming optical array. If the structure is indeed an emergent property of the motion information, then it would seem that the static images are insufficient for explaining the percept.

Figure 1.1: Six sequentially sampled frames depicting a point–light walker at different phases of the gait cycle.

This conclusion was anticipated by Gibson (1966), who rejected the view that visual perception is based on a statical model and argued persuasively for the primacy of motion in visual perception. In essence, his position was that visual information in the optic array is changing continuously through both self– and object–motion, and thus it seemed reasonable to assume that we had evolved to perceive motion information directly. This theoretical perspective led eventually to a significant reinterpretation regarding how we perceive the visual world, and it is much more common today to study the perception of the changing optic array as opposed to the perception of a static image.

Aside from the field of motion perception, the vast majority of psychological research is still primarily oriented toward statical models of behavior. In general, a statical model assumes that the relevant state of the modeled system remains constant, and thus focuses exclusively on the current relations between the state variables (Ward, 2002). For example, human memory has been modeled over the past 150 years as a static system consisting initially of two general systems of memory, short term and long term, and later expanded to include episodic and semantic memory systems. In spite of each of these systems differing in terms of their temporal dynamics, little attention is given to how these memories develop over time. The majority of the research has focused on the output or the product of the system. For example, research reveals that we remember more items in working memory when we rehearse them or store them categorically. Ironically, most of these models emphasize their relationships between variables independent of time, even though memory is inherently a temporal process. Likewise, learning is a time–critical process, as new knowledge and skills are organized over time, but we tend to focus on the products or outcomes of this process. What is lacking in these and other domains is a way of modeling how the behavior changes over time.

In order to avoid any confusion, let me emphasize that my intent is not to dismiss or minimize the importance of what I have referred to as statical models. Analysis of any fundamental process first requires identification and categorization in order to establish the meaning and reliability of the observed phenomena (Rapoport, 1972). For example, the study of cognitive development has involved repeated efforts to understand what children know and don't know about concepts at different ages. This knowledge is a prerequisite to trying to understand how these concepts develop (Flavell, 1971; Siegler & Alibali, 2005). Without statical models of behavior, it is doubtful that scientists could agree on the variables that should be studied (cf. Ward, 2002). Still, studying the changes in these variables and how they evolve over time is necessary for obtaining a more complete understanding of behavior. It would thus be misleading to suggest that either model is sufficient for understanding human behavior, because these models are complementary and not contradictory.

The challenge for the investigator is to know the strengths and limitations of both models. As a case in point, Bob Freedland and I were interested in studying the transition in human infants from belly crawling to hands–and–knees crawling (Freedland & Bertenthal, 1994). At the time of this study, it was commonly reported in the literature that hands–and–knees crawling involved moving only one limb at a time akin to the interlimb pattern produced by a horse when walking. Interestingly, the majority of evidence for this report was not based on empirical data, but rather was based on applying a static model for explaining how the infant remained balanced while supporting the trunk off the ground. In essence, this model stipulates that a minimum of three limbs is required to keep the center of mass of the body over the polygon of support formed by the limbs in order to maintain a balanced system and to avoid tipping (Raibert, 1986). The problem with this logic is that it was based on the wrong model. Animals sometimes use three legs to balance when they move slowly, but they usually move faster and more flexibly by employing a dynamically balanced system (Alexander, 1992). During dynamic balance, quadrupeds support themselves with only two limbs during portions of the gait cycle. The same is true for human infants who tend to not move one limb at a time while crawling, but instead move diagonally opposed limbs simultaneously and 180° out of phase with the other pair of limbs. Freedland and I confirmed this prediction with motion analyses of the infant's crawling pattern, but it is debatable whether we would have collected the requisite data if we had assumed that crawling conformed to a statical as opposed to a dynamical model.

1.2 | TIME SCALES OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR |

Why is so little attention devoted to the dynamics of behavior? My sense is that the temporal dimension is often obscured by the time scale at which a behavior is studied. For example, we think of social behaviors as learned over an extended period of time, but once acquired, these behaviors function automatically in a seemingly fixed way. Of course, these behaviors are all dynamically assembled each time they're executed, but the assembly often takes place at a faster time scale than our sampling rate. It is thus essential to consider in our modeling that human behaviors operate at multiple time scales, and that these time scales are hierarchically related.

An excellent framework for thinking about the relation between these time scales was proposed by Alan Newell (1990). In this framework, intelligent systems are built up from multiple levels of systems in hierarchical fashion (see Table 1.1). Each system is a collection of elements or components that are linked together and interact, thus producing behavior. As one moves up the hierarchy of system levels, size increases and speed decreases. Expansion occurs in time as well. It was estimated that each new level would be about a factor of 10 bigger than the next lower level.

Table 1.1: Time Scale of Human Action

Scale

(sec) | Time Units | System | World

(theory) |

107

106

105 | months

weeks

days | | Social Band |

104

103

102 | hours

10 min

minutes | Task

Task

Task | Rational Band |

101

100

10−1 | 10 sec

1 sec

100 ms | Unit task

Operations

Deliberate act | Cognitive Band |

10−2

10−3

10−4 | 10 ms

1 ms

100 µs | Neural circuit

Neuron

Organelle | Biological Band |

Let's examine these levels in a little more detail. In the biological band, we are dealing with neuronal processes in the brain. Information is coded by neural activity that lasts approximately 1ms for individual neurons, and 10ms for neural circuits. From this timing information, it is possible to establish real–time constraints on cognition as a function of neural activity. For example, there are approximately available 100 neural operations per second of cognitive activity. A simple sentence, such as “Please pass the salt,” or your reaction to it will take approximately 1sec. By contrast, rapid transit chess (10s per move) requires multiple cognitive operations (encode opponent's move, understand consequences, decide on a move and make it), and thus it takes longer than a single cognitive operation. This task would be impossible for humans if it took more than a few seconds to engage in each of the necessary cognitive operations. For similar reasons, we would predict that humans could not play 1 sec chess in an intelligent fashion.

As can be seen in Table 1.1, it is possible for humans to cognitively process information at rates faster than 1sec, and these rates are often assessed in reaction time experiments. It is possible...