![]()

Part I

Clinical chapters

This book is divided broadly into two parts: clinical psychoanalytic chapters, and chapters deriving from the application of psychoanalysis to social and cultural phenomena. This division reflects the influence of two disciplines: social anthropology (my first discipline), and the discipline I have worked in for most of my life—psychoanalysis. In the early 1980s I was fortunate enough to combine PhD fieldwork in social anthropology with my interest in the psychoanalysis of severe disturbance by joining an unusual team working at the Maudsley Hospital in London. These psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, led by Henri Rey, Murray Jackson, and Robert Cawley, together with a group of nurses and psychotherapists, developed an experimental inpatient unit for the treatment of psychosis using psychoanalytic knowledge as the basis of the psychiatric treatment model. The work was effective and was recorded in the book Unimaginable Storms: A Search for Meaning in Psychosis (Karnac Books, 1994). A résumé of the work is given at the end of this book, taken from the introduction and conclusion to Unimaginable Storms.

Unquestionably, the striking feature for me of this treatment model was the capacity of the team to arrive at an understanding of the unconscious meaning of the individual patient’s illness in the context of the person’s life history, personality development, internal object world, and current relationships with staff. The therapeutic benefit of this knowledge, conveyed within the analytic relationship and in various other forms by the staff, opened up new opportunities for patients. Time and again I recall being surprised by the extent to which the analysts and patients were able to converse in such depth and with such honesty. It seemed to me that what appeared at the outset to be a potential for serious misunderstanding, conflicts, impasses, and bizarre behavior by the patients, slowly and gradually gave way to a focused, sane discussion between two rational adults about what it felt like to have gone mad. How such a conversation can occur is, I suggest, an important question for the practice of psychiatry. It is a form of highly personal engagement, based on elucidation of a mutually agreed, truthful understanding of the nature of the individual’s internal world, which is capable of contributing to the healing of even the most serious of disturbances. Today, I believe this to be an even more important question for psychiatry, as we have undergone a cultural change in attitudes towards mental illness during recent years. This trend has led us away from the enduring therapeutic benefit of self-knowledge and a capacity to engage deeply in human relationships, and towards wholesale reliance on psychopharmacology and short-term treatments. These contemporary methods, while helpful for some individuals, perhaps most in the area of the containment of symptoms, too often have the side-effect of colluding with the core psychological premise of much psychotic thinking as a result of the scant attention paid to the need for human relatedness, without which none of us feels human and truly alive. This premise is: Human relationships have proved to be a source of disaster and unimaginable suffering. I have fallen out of their orbit and need to be reconnected to them if life is ever to have meaning again. I fear that this is impossible as I have become so removed from people.

It is not difficult to discern from such a state of mind that the amount of work required for the patient to reestablish trust in other people, and thereby in oneself, is considerable. It is, in fact, a Herculean undertaking for patient and analyst, and may take years to accomplish, not weeks or months. Such commitment to the recovery of psychotic individuals, and the patience required on both sides, is no longer fashionable. This does not mean that patients accept this situation. A regular occurrence, at least in my consulting room, is a situation in which a chronically ill individual conveys awareness of his or her plight and indicates that they are willing to try to do whatever is necessary to alleviate their despair. In their honesty and urgency, they underscore Freud’s observation that their troubles lie on the surface, and today we know that they are amenable to intervention, despite their crippling complexity. Their misfortunate is that fewer and fewer psychoanalysts are being trained to work analytically with them, so the prospect of receiving the understanding and help they need to recover their humanity is reduced.

In the following pages, I discuss some ideas and ways of working that I have learned during the complex process of trying to understand individuals who are suffering crippling psychotic anxieties. Most of this work has been undertaken in private analytic practice, but a proportion of it has taken place in the British National Health Service and as a clinical consultant to two institutions providing residential psychoanalytic treatment: Boyer House in San Rafael, California (now closed), and Arbours Crisis Centre in London.

![]()

Chapter 1

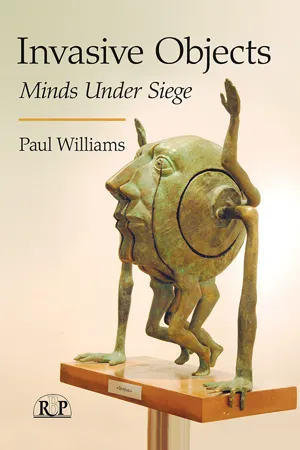

Incorporation of an invasive object1

I shall try to sketch out a way in which symbolic functioning appears to be undermined in certain cases of severe disturbance. The failure I shall discuss reflects a developmental crisis, features of which became apparent to me during the analyses of three patients, two of whom I shall discuss here. Each of the patients, though very different in important respects and brought up in dissimilar circumstances, suffered serious narcissistic disturbances. A characteristic the patients shared was the experience of having incorporated an object with random, invasive tendencies, which at times could lead them to the brink of, or into, psychosis. By “incorporation of an invasive object,” I wish to convey a primitive, violent introjection of aspects of an object that creates the experience of inundation by the object that can give rise to serious disturbance in the nascent personality. This form of pathological “proto-identification” takes place in early infancy and is consequent upon precocious interaction between infant and object, including, critically, failure of containment and maternal alpha-function (Bion, 1970).

Under normal circumstances, incorporation is the earliest mode of relating in which the infant feels himself to be at one with the other and is unaware of separation between the two personalities (Fenichel, 1945; Searles, 1951; Sterba, 1957). This experience decreases if development proceeds relatively unimpeded. If development is impeded, the experience can persist, leading to an equation between relatedness and engulfment, in which one personality is felt to be devouring the other (Searles, 1951, p. 39). The impulse to unite incorporatively with the other as a defense against separation anxiety has been widely discussed.2 All note how physical experiences are a characteristic of processes of incorporation, in contrast to the fantasy dimension of introjection into the ego, which assumed importance in Klein’s (1935) thinking and which she discusses in the context of incorporative activity and the genesis of psychosis.

The patients I shall describe manifested incorporative self-states in the form of both bodily and psychological symptoms. I shall suggest that they underwent traumatic disruption to the psyche-soma at a time when their sense of self was barely formed and the psyche-soma had yet to undergo differentiation. A primitive introject appears to have been installed in their minds and their experience of their bodies that was held by them to belong to their own self-representational system. Contradictorily, at the same time, this introjected presence was experienced as a concrete presence of a disturbing “foreign body” inside them.

The experience of something that is not a part of the self, yet is confused with the self, can create not only psychic conflict, but also incompatible or “heterogeneous” states of mind (Quinodoz, 2001). “Heterogeneity” is denoted as the product of a “heterogeneous constitution of the ego” (Green, 1993). This description reflects Bion’s (1967) observation that “there is a psychotic personality concealed by neurosis as the psychotic personality is screened by psychosis in the psychotic, that has to be laid bare and dealt with” (p. 63).

Heterogeneous patients present for help because they suffer from their heterogeneity, unlike the majority (Quinodoz, 2001). This heterogeneous quality is implicated in the vulnerability and intrapsychic confusion of the patients I shall describe and seems to have affected not only the way in which these patients related, but also how their thinking developed.

Clinical Example 1: James

James, 27, entered analysis after a series of failed relationships culminating in depressive attacks with suicidal ideation. He possessed an unusually high IQ and was capable of abstract levels of thought beyond his years, and of grasping the nub of ideas and arguments. There was a paranoid tinge to many of his observations and his attention to others’ motivation seemed compulsive. James was quintessentially a self-made man. He had failed at school but as an adult had become successful in business. His father, an addict, died in his 40s of a drug overdose. James was a replacement child; a previous son had died, apparently unmourned, 10 months before James’s birth, his mother having been advised by her doctor to get pregnant again straight away. James’s mother seems to have been an unstable woman consumed by hatred and grievances. He said his parents fought continuously during the marriage over affairs each accused the other of having. He recalled as a child sitting in horror in his pajamas on the stairs while his parents brawled. He left home at 16 and remained unreconciled to them. He saw his mother again once when she was unconscious on her deathbed in hospital.

I was struck from the outset by the speed with which James seemed to reach the meaning of his fantasies and dreams. He would get there before me, with impressive intuitions, yet without making me feel excluded. He strove to be a “model” analysand. It became apparent that he needed to control the analysis, subtly and diplomatically, and that he suffered intense anxieties when he did not feel in control. He revealed that his controls were, in fantasy, controls over my thoughts. Why he needed to control my thoughts was not clear to him or me. His dream life provided evidence of a serious disturbance of the self. He dreamed repeatedly that he had murdered someone. The body, a male, lay buried under a road; it was a secret, but the police were piecing together clues and were on his trail. He developed insomnia to avoid the nightmares. James’s compliant, controlling behavior decreased as he became more depressed and nihilistic during the second year of analysis. In one session he lay contemplating suicide and said, with piercing dejection, “I came into analysis for consolation. I knew nothing could ever come of my life.”

I was affected by his comment, which was said with no trace of defensiveness, and my response—an intense sadness—persisted after the session. I realized that I had been struck by, to paraphrase Marion Milner, a “thought too big for its concept.”3 I wondered whether analysis-as-consolation masked, for James, the site of an experience of annihilation anxiety. This phenomenon, which has been referred to as “a memorial space for psychic death” (Grand, 2000), denotes unspeakable, traumatic events that are felt to always be present, yet must remain absent. Metabolization through language is the means we possess of approaching such catastrophe, yet this is disbarred, as language is experienced as unable to approximate the scale of the events involved.

I shall pass to a period in the third year during which James decided he wanted to quit analysis and his suicidal feelings took a psychotic turn. He had become disillusioned and was prone to long, angry silences. “Is this all there is?” he would complain bitterly, following stretches of withdrawal. He could be abusive, accusing me of keeping him in analysis to maintain the vain illusion that I could help him. If he felt I might be close to understanding what he was feeling, he would lash out contemptuously—for example, “This [analysis] is hypocrisy. It deceives, it lies, it’s wanking. It’s a middle-class fix. You haven’t got the first idea about me or what people like me go through.” He told me he felt burned out, disgusted by himself, and hopeless. The nightmare of having killed someone preoccupied him, including during the day, making it increasingly difficult for him to function in his work. As his condition worsened, I became anxious for his safety, as he was immersed in what appeared to be a developing transference psychosis. This situation continued for some weeks. I talked with him about his profound disillusion with me and the unmanageable feelings of despair and rage this engendered.

An event occurred in which James communicated his despair in a way that I felt revealed his having incorporated an object characterized specifically by invasiveness. James had spent most of this particular Wednesday session in tormented distraction at his inability to control his feelings of disdain towards his female partner, who he was afraid would leave him. He described unpleasant scenes between them that left him confused and suicidal. The idea that there might be no change possible appalled him. He twisted and turned on the couch, as though in bodily pain. I told him how afraid I thought he was of becoming more and more like his parents, at home and here with me, and how feelings of growing fear, resentment, and hatred of his partner and me pushed him into a terrible sense of failure. Feeling trapped in hate and fear, like his parents, destroyed his power and hope, turning him into a needy, hopeless child who he hated. The only way out he could imagine, in the absence of anyone to help him, was to kill himself, but even this didn’t work as he still didn’t have anyone who understood what he was going through. James’s writhing stopped and his body relaxed. He appeared to be relieved at having his confusion and fear acknowledged. However, he became more restless and what appeared to be a more thoughtful silence turned out to be not the case at all. He slowly and purposefully got off the couch, stared at me—or rather through me—and shouted with unbridled hatred, “Keep your platitudes to yourself, you stupid fucking moron.”

This outburst of violent, narcissistic rage seemed also to embody a psychotic effort to try to rid himself of an alien presence or state of mind, of which I appeared to have been the incarnation. He fell silent, walked unsteadily round the room, became distracted, and eventually sat on the edge of the couch, trembling. I felt assaulted by the attack—fear and anger welled up inside me. I could not think of anything appropriate to say, only a wish to protect myself. I felt stripped of a capacity to contain the situation. James sat for some time holding his head in his hands. I recall the session ended with me asking him whether he felt able to manage getting home. The next day James was in a distressed, confused state.

I don’t understand. I can’t remember it clearly … it is like a fog … something just came over me. I don’t know how to explain it … I’m sorry. I feel a bit like it now, kind of stunned. My head feels full … there is so much going on that I can’t think and my legs feel like lead … like my body wants to collapse. I don’t quite know where I am in this. I don’t know why I should scream at you like that …

He continued in this bewildered, anxious way that seemed to combine guilt about what he felt he had done to me and confused feelings of dread and relief at having lost control of himself. I said to him that, although he felt a need to apologize, what was striking to me was that he had allowed me to see some of his deepest feelings, including those about me, without camouflage, something that I doubted he had done often, if ever, in his life. He said,

I don’t think I had any choice; it doesn’t feel like I did … it wasn’t taking a risk. Something exploded. It was anger but there’s something not right about that … it’s not the whole feeling. Something in me could have killed you. I wasn’t thinking this when it happened but it makes me think that something in me wanted to smash and smash you and shut you up so I didn’t have to listen any more, eve...