1

MAYA CIVILIZATION IN PERSPECTIVE

The ancient Maya inspire awe and fascination in each of us today as they did to the first explorers more than two centuries ago, because of their cities buried in the tropical jungle and because so much about them is unknown. Two basic questions about them are: Where did they come from? And why did they disappear? The answers remain shrouded in an aura of mystery. This book explores their earliest beginnings with the hope that knowledge of how they built their civilization will also give us clues to what caused them to decline.

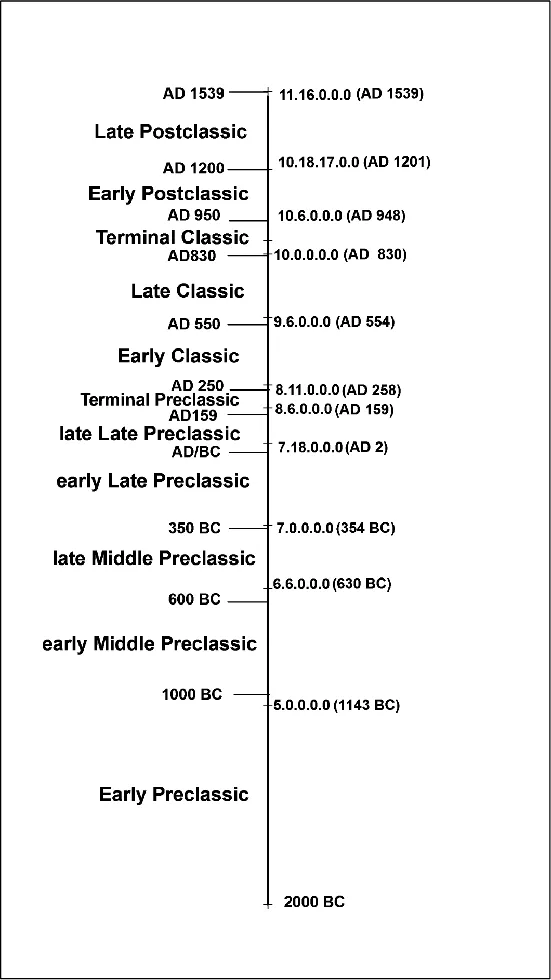

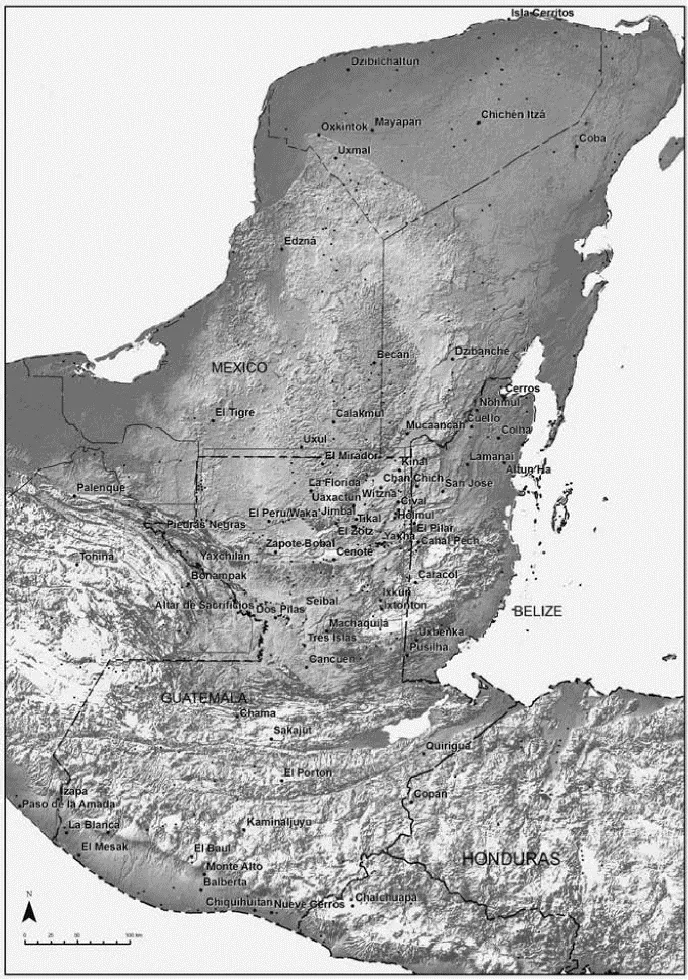

Contrary to common perception, we know quite a bit about the great Classic Maya civilization, thanks to over 100 years of archaeological excavations and more recent hieroglyphic decipherments. We refer to the “Classic Maya” as the people who built Tikal and many other great cities deep in the jungles of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras during the first millennium AD. We use the term “Classic” to distinguish them from their predecessors, the Formative or Preclassic Maya of the first millennium BC, and from their successors, the Postclassic Maya who thrived until the arrival of Europeans in the 15th century.

But these ancestors are, of course, one and the same people as the present-day Maya who still inhabit the Yucatan Peninsula, and walk the streets of Guatemala City, Chichicastenango, San Cristobal de Las Casas, Merida and countless villages. The Maya are at a fundamental level a people united by one culture that underwent various transformations through time. Though now fragmented by more than 31 Maya languages1 (Sergio Romero, personal communication, 2010), all share the worldview and agrarian way of life of their ancestors while becoming increasingly integrated in western culture.

Today, researchers no longer consider the terms Preclassic, Classic and Postclassic as stages of cultural evolution or devolution, but simply as arbitrary time divisions that are too engrained in our scholarly literature to be changed. As this book will demonstrate, far from being a primitive ancestor of the more evolved Classic period, the Preclassic period produced the first amalgamation of complex social norms, interactions, and production of material representations of the sort we normally associate with the greatest civilizations in world history. The Preclassic period also witnessed the demise of this first incarnation of Maya civilization.

In the same way that ancient and modern Maya conceived of their own lives as existing in one of several cycles of creation, so many archaeologists today are replacing a linear evolutionary perspective of ancient culture—one that privileged progress, complex institutions and hierarchy—with another that focuses on cycles of aggregation and fragmentation of communities. From this new point of view, the making of culture is no longer seen as a process of emerging governmental institutions which can be reconstructed through their material correlates, but as a process of place-making, as the emergence of traditions of specific people tied to specific places (Pauketat 2007). In this perspective, communities were created in the process of place-making, including the construction of monumental buildings. Forms of government developed from this process, not vice versa.

To explore the period before the Classic most meaningfully, however, we should briefly review the Classic Maya themselves, and recent scholarship which has revised our knowledge. Thanks mainly to the decipherment of epigraphic inscriptions, we know much more today than even 20 years ago about Classic Maya civilization. We have gone from discussing abstract processes of cultural interaction (trade, migration, warfare) to delving into the history of kingdoms and the deeds of their rulers. But the general public still associates the Maya mainly with the towering pyramids of a mysterious culture. One ruined city, Tikal, figures prominently in western pop culture as the Rebel Alliance’s spaceship base in the Star Wars IV film. With Chichén Itzá, the great city of the north, Tulum, the stunning coastal center and the beautifully sculpted Copan in Honduras, Tikal is one of the archaeological sites that today receive the greatest number of visitors from every corner of the globe. The images and narratives promoted everywhere by tour guides, brochures and scholarly books are typically the same:

• The Maya as great astronomers.

• The Maya as mathematicians and architects.

• The mysterious calendar and its prophecies—2012 and the end of the world recently the most popular.

• The mysterious Maya collapse.

• Their formidably complex hieroglyphic writing, which was baffling until deciphered by some of the most ingenious scholars of our time.

• Most of all, the Classic Maya fascinate us for having tamed the inhospitable jungle and built a thriving civilization with what today we consider very limited resources.

An overview of Classic Maya research

An overview of what we know about the Classic Maya includes the two main sources of evidence: archaeology and epigraphy. The year 2009 marked an important milestone in Maya archaeology—the hundredth anniversary of the first archaeological excavation of a Maya site. This was the Peabody Museum of Harvard University’s expedition to Holmul, Peten, Guatemala, led by a young graduate student, Raymond E. Merwin (Merwin and Vaillant 1932). In the following expedition, Merwin and his mentor, Alfred Tozzer, completed the work begun at Tikal by two earlier European explorers, Alfred Maudslay (Maudslay 1889–1902) and Teobert Maler (Maler 1911; Tozzer 1911). Following these pioneering efforts, each generation of Maya archaeologists excavated new sites in the harsh jungles of Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. With each generation, the database increased by orders of magnitude allowing more complex research questions to be posed.

When seen in historical perspective, the older archaeological sample appears to be biased towards certain kinds of site. Typically, the largest sites in the Lowlands were targeted, neglecting medium-sized and small settlements. Also, many more centers with inscriptions were excavated than those without, leaving a whole section of ancient Maya society and its geography unexplored. Much of the research conducted since the 1960s has attempted to correct this imbalance, but more sites with inscriptions than not continue to be targeted by archaeologists. At the same time, the deciphering of hieroglyphs spurred a wave of new excavations at royal capitals rich in inscriptions. Filling gaps in Maya history became a major priority.

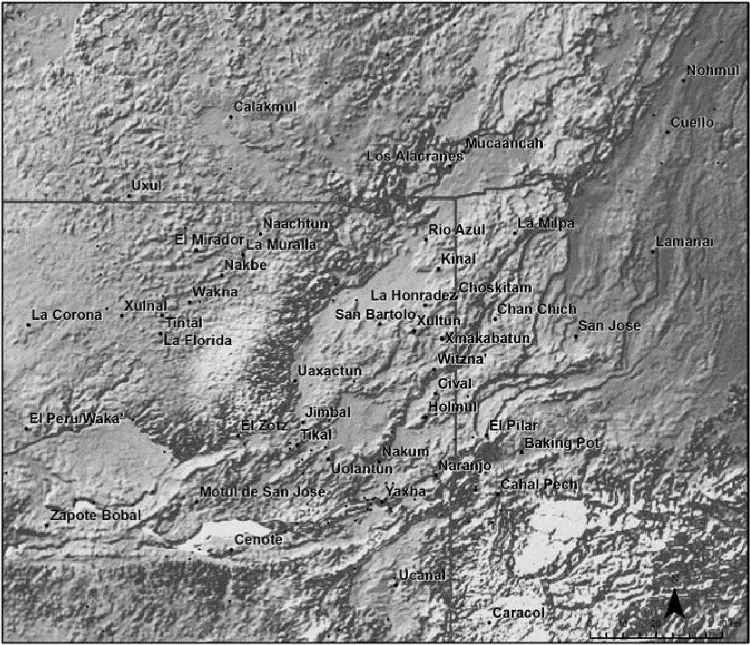

The history of Maya archaeology deserves a more detailed look, beginning with the sponsoring by the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW) of large-scale digs at Maya sites between 1915 and 1958.2 The first large-scale Lowland excavation project at Chichén Itzá was led by Sylvanus G. Morley from 1923 to 1940. Chichén Itzá was chosen because of its accessibility, wonderful art and architecture, and also because of the wealth of artifacts dredged from its cenote3 in 1904 by an amateur American archaeologist, Edward H. Thompson. The second great Lowland Maya dig was led by A. Ledyard Smith at Uaxactun from 1926 to 1937. Compared to Chichén Itzá, this was an infinitely more difficult site to work. In the heart of the remote Peten forest, it could be reached only by several days’ mule-train travel. It was selected because the earliest carved inscription was found there in 1916 (Stela 9). The goal was to explore the beginnings of Maya civilization “in its purest state” (Morley 1943: 205). A Guatemalan archaeologist, Juan Antonio Valdés, resumed excavations at Uaxactun in 1983–1985. The Highlands of Guatemala and Honduras were the focus of CIW excavations in the 1930s and 1940s at Kaminaljuyú and Copan (Kidder et al. 1946; Morley 1943; Stromsvik 1946). The CIW’s final project investigated the last phase of Maya civilization, just prior to the Spanish conquest, at Mayapan in the Mexican state of Yucatan (Pollock et al. 1962).

Following the CIW model, the University of Pennsylvania carried out excavations and restorations at Tikal from 1955 to 1970, first under Ed Shook, then under William R. Coe (Hammond 1982). In the 1980s Guatemala sponsored its own excavations, led by Juan Pedro Laporte. Presently, Guatemalan-led excavations at Tikal are uncovering its greatest pyramid, Temple IV. On invitation by the Honduran government, Harvard planned a long-term project at Copan (Willey et al. 1975) that lasted until 1996. In Mexico, large-scale projects were carried out at Dzibilchaltun (Andrews and Andrews 1980), Palenque (Ruz Lhuillier 1955), Cobá (Folan et al. 1983) and more recently at Calakmul (Willey et al. 1975; Folan et al. 2001; Carrasco 1996), Oxkintok (Rivera Dorado 1987) and Ek Balam (Bey et al. 1998), to name just a few.

As is evident from this summary, Maya archaeology in the southern Lowlands, at least, was until recently site-based. That is, ceremonial centers, along with their temples, palaces, plazas and tombs, have been the focus of investigation more than other aspects of Maya landscape and society. This historically understandable bias of Maya archaeology has not gone unremarked

by the many researchers who have tried to gather a more complete picture of the ancient Maya and their cultural trajectory. As early as 1953, Gordon Willey introduced “total-coverage survey” as one method to document settlement and human–environment relations (Willey 1953). Such an approach, however, was suited to the open landscapes of northern Yucatan, the Belize River Valley and Highland Mexico but could find little application deep in the jungles of the southern Lowlands. A more suitable method, the transect survey, was first introduced by CIW’s Ricketson at Uaxactun (Ricketson and Ricketson 1937) and was later perfected by Dennis Puleston (Puleston 1983) at Tikal for the Penn project. Narrow bands of forest were mapped in each cardinal direction in order to get a measure of housing density from the site’s center to the periphery. But even this was a single-site-centered approach. Later Anabel Ford (1986) carried out the first “inter-site transect mapping” of a 30-kilometer strip of settlement between Tikal and Yaxha.

Today, with the help of Global Positioning System technology, we can expand our surveys from charting sites and linear tran...