1 Introduction

Ethnolinguistic Diversity in Language and Literacy Education

Marcia Farr, Lisya Seloni, and Juyoung Song

Introduction: Defining Terms

In an increasingly globalized world, different peoples, languages, ideas, cultural practices, and material goods can be found far from their traditional homes. In fact, many places in the world now have relatively low percentages of indigenous populations. Although some scholars trace globalization processes back many centuries (Frank, 1996), the ethnolinguistic diversity we focus on in this book can be traced to the European colonization of the Americas and, more recently, to migration during the twentieth century. In the United States, this multiplicity of peoples and languages has spread from large cities, which have been diverse since their very beginnings (see, for example, Farr, 2007), to small towns and rural counties throughout the country.

The term ethnolinguistic minimally refers to all the speech codes, or the languages and dialects, spoken by the various groups of people who either are indigenous to, or have migrated to (from colonial times on), the contemporary United States. Current ethnolinguistic diversity in the U.S. includes many, if not all, of the languages of the world, various varieties (or dialects) of those languages, and Creole languages formed from mixing two or more languages. English, for example, now has many international varieties, as well as dialects within those varieties (Crystal, 2003). Moreover, English-based Creoles emerged (as new languages) when English came into contact with indigenous languages, combining an English lexicon with the indigenous grammar (Nichols, 2004). Such Creoles in the U.S. include Gullah (in South Carolina), Hawaiian Creole, and, more recently, other varieties such as Jamaican Creole, Nigerian Pidgin English, and Sierra Leone Krio. English-based Creoles are similar to global “nativized” varieties of English like Indian English in that all of these “new Englishes” emerged through the colonial spread of English and its contact with other languages (Mufwene, 2000; Winford, 1997, 1998). Even some vernacular dialects, such as African American Vernacular English, are theorized (by some but not all scholars) to have evolved from former Creoles, such as Gullah (Green, 2002), and thus from the spread of English from England to the American continent in contact with the West African languages which the African slaves spoke (Green, 2002; Rickford & Rickford, 2000).

Creole languages, like all languages, also have their own variations, from basolects (the varieties that are most vernacular and “of the people”) to mesolects (middle-range varieties) to acrolects (varieties that are closest to the standard language). For example, Jamaican Creole is not one uniform language, but a range of variations relatively distant from or close to Jamaican Standard English. Thus variation is everywhere: all languages have dialects and even so-called Standard languages exist more at the level of abstraction than reality. Standard U.S. English, for example, is perhaps defined most easily by the absence of socially marked vernacular features (such as multiple negatives, the use of ain’t), than by what features characterize it, since it too varies across speakers, contexts, and modes (speech, print, electronic media). Out of this wide range of variation, we focus in this book on vernacular varieties of English; varieties of Spanish; Chinese, Korean, and Japanese; and Caribbean Creole English.

Linguistic codes, however, do not exist in a vacuum; rather, they are always used in, and draw meaning from, particular cultural contexts. One cannot communicate simply by knowing the grammar and lexicon of a language; one must also understand the cultural context in order to communicate meaning. Consequently, we use the phrase ethnolinguistic diversity to refer not only to the linguistic codes used by various populations, but also to the cultural meanings embedded in those codes. Cultural meanings are inevitably embedded not only in linguistic codes, of course, but also in social structure, and social structure implicates such aspects of identity as race/ethnicity, gender, and social class. Since these terms are rife with conflict and debate, we briefly discuss here how they can be understood in this book.

First, we draw from the term ethnicity rather than race for the term ethnolinguistic, since language diversity has nothing to do with race (and everything to do with society and culture). Children learn the languages, and particular varieties of those languages, within the families and communities in which they are socialized, not according to the so-called “racial” group to which they belong. Race itself, of course, is a social, not a biological, construct; there is more genetic variation within one “racial” group, for example, than across such groups (see http://www.aaanet.org/resources/A-Public-Education-Program.cfm for clarification about what “race” is and is not). Thus the capacity for language is shared across the human race, but particular varieties of language emerge in different places among different groups of speakers according to local social and cultural constraints. Key to this understanding of language variation is the notion of identity: using a particular variety of a language indicates, and even constructs on-the-spot, specific identities, and people may choose (consciously or unconsciously) between varieties and/or languages to construct varying identities depending on the context. For example, a child may learn to use a vernacular English (or Spanish, Chinese, etc.) at home, but a more standard English (or Spanish, Chinese, etc.) at school or church. For bilingual populations, a particular variety of a heritage language (e.g., Mexican rural Spanish) may be used at home within the family, and a more formal variety of a second language (e.g., “standard” U.S. English) may be used at school (and vernacular varieties of the second language also are often learned and used in yet other contexts).

Vernacular, of course, refers to a local variety of a language in a particular region (as opposed to varieties that are considered more “cultured,” literary, or formal, i.e., the “normal spoken form of a language” (http://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/vernacular). Thus vernacular refers to language (or another aspect of society) that is local, or “of the folk.” This term is now preferred over the traditional term dialect, since the latter has accumulated some low-status connotations (Adger, Wolfram & Christian, 2007). The term vernacular brings up another aspect of linguistic diversity treated in this book: that of socioeconomic status or class. Vernacular speech varieties are most often associated with working-class speakers, although many non-working-class speakers also use a vernacular variety, as well as other, more formal varieties, as already noted (see, for example, Rickford & Rickford, 2000). Although the notion of socioeconomic class is treated in traditional sociolinguistic studies as a stable aspect of a person’s identity (based on occupation, income, education, and other measurable variables), some recent research has treated this notion more critically. Rickford (1986) critiques the use of such static class labels, arguing that they might not even be relevant local categories for some communities, and that this is a matter to be determined ethnographically. Eckert (2000) builds on this critique by arguing that vernacular varieties can be viewed instead as resources people use to express a local identity in opposition to other identities. Thus someone may choose to express a (valued) working-class identity in particular contexts for particular reasons.

Gender is a third aspect of identity that intersects in complex ways with other aspects such as ethnicity, class, and age. Here we use the notion of gender as distinct from biological sex, as “the meanings that a particular society gives to the physical or biological traits that differentiate males and females. These meanings provide members of a society with ideas about how to act, what to believe, and how to make sense of their experiences” (Mascia-Lees & Johnson Black, 2000, p. 1).

Moreover, there are multiple “femininities” and “masculinities” in different communities and cultures (Stern, 1995), in spite of the fact that many (although not all) societies insist on only two categories, male and female. In reality, however, as already noted for social class, people use gendered linguistic features as resources to express varying identities in particular contexts for particular reasons (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2003). In addition, as with the discussion of social class, gender is an aspect of identity that cannot be applied as a static label; instead, the particular meanings of gender must be determined ethnographically for different communities, and even for different parts of the same community.

Thus far we have defined important terms as aspects of identity tied to ethnolinguistic diversity. Although such diversity is evident in many settings, a particularly salient one is the public school. In the next section we consider ethnolinguistic diversity in the U.S. generally and in U.S. schools, focusing on important issues that emerge at the intersection of such diversity with language and literacy education.

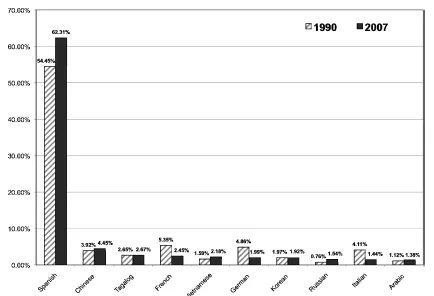

Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Schooling

A basic premise of this book is that research-based understandings of the ethnolinguistic diversity among students are crucial to effective language and literacy education. Although English is clearly the dominant language in the U.S., the presence of other languages is notable: over 55 million people (20 percent of those aged 5 and older) speak a language other than English in the U.S., which is one out of every five people (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007). This figure has increased by almost 2 percent since 2000 and by 6 percent since 1990 (for more statistics, see Wiley & de Klerk in this volume). Among these other languages, Spanish (including Spanish creoles) is the most common language—it is spoken by 34,547,077 people (62 percent of all speakers of other languages and 12 percent of the U.S. population over 5 years of age). Spanish is followed by Chinese (2,464,572 or 4 percent), Tagalog (1,480,429 or 3 percent), French, (1,355,805 or 2 percent), and Vietnamese (1,207,004 or 2 percent). Figure 1.1 shows the ten most widely spoken languages other than English in the U.S.

As can be seen in Figure 1.1, Spanish is by far the most widely spoken language (other than English) in the U.S., and the number of Spanish speakers has increased since 1990. Speakers of Asian and Pacific languages such as Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Korean also increased, totaling 3 percent of the U.S. population 5 and older in 2007. In contrast, speakers of European languages such as Italian, German, and French, decreased since 1990, yet in 2007 still were spoken by 4 percent of the U.S. population 5 and older.

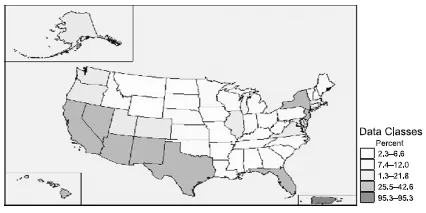

Geographically, speakers of languages other than English are spread throughout the nation, although they are most concentrated in particular regions and in metropolitan areas. The map in Figure 1.2 shows the state-level percentages of people over 5 speaking a language other than English at home in 2007.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of Ten Most Widely Spoken Languages other than English in 2007 and Their Changes between 2007 and 1990.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau (1990) and U.S. Census Bureau (2007).

As can be seen in Figure 1.2, states in the South and West regions of the U.S. generally have higher percentages than those in the East or Midwest regions. Particular states in the East and Midwest, however, also show high percentages. The state of California has the highest percentage (43%), indicating that almost one out of two people speak a language other than English. Other states with more than 20 percent who speak another language include (in descending order) New Mexico (36%), New York (29%), Arizona (29%), New Jersey (28%), Nevada (27%), Florida (26%), Hawaii (26%), Illinois (22%), Rhode Island (21%), and Massachusetts (20%).

It is important to point out, however, that in 2007, more than half of the people (56 percent) who reported speaking another language also reported that they speak English “very well,” and an additional 20 percent that they speak English “well.” This means that over two thirds (76 percent) of those who speak a non-English language are bilingual and have good English skills. This figure is even higher among younger age groups: 92 percent of 5–17-year-olds who speak a non-English language also speak English either very well or well. Only 8 percent of these children and adolescents answered that they do not have good English skills or have no English skills at all. Out of the total number of 5–17-year-olds in the U.S. (53,237,254), however, only 8 percent (10,918,344) are bilingual; the rest speak only English. The number of older bilinguals is larger: 20 percent of those 18–64 (39,237,930) speak a language other than English, and 73 percent of these bilingual adults speak English well or very well. We can infer from the discrepancy between the percentage of child and adolescent bilinguals vs. adult bilinguals that English continues to be the dominant U.S. language and that many younger speakers are likely to become English-dominant, even if they retain some ability in a non-English language. The most striking conclusion from all these figures, however, is that English is not even close to being challenged as the dominant and primary language of the U.S., in spite of public fears to the contrary (see Wiley & de Klerk’s chapter for more discussion of such fears).

Figure 1.2 Percentage of People (5 Years and Over) Who Speak a Language other than English at Home in 2007.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2007).

Given the unchallenged status of English in the U.S., what is underdiscussed yet critical for education is how to assist the children and adolescents in K–12 schools who speak heritage languages and have little or no facility in English. In addition, it is important to address the needs of bilingual populations in school (those who speak both a heritage language and English)—currently one out of a dozen children nationally—in terms of how to accommodate their cultural and linguistic characteristics in supporting the development of both languages (and literacies). Meeting these students’ needs begins with research-based understandings of their heritage cultures and the roles of their native languages (and varieties of those languages) in their academic and personal lives. Such an understanding is urgent as schooling only in academic English can lead to identity conflicts and even to leaving school. In fact, those students who speak vernacular varieties of English or languages other than English drop out of school at disproportionately high rates, indicating a relationship between students’ language backgrounds, performance scores in school, and dropout rates (see McCarty et al.’s chapter for Native American students and Charity Hudley’s for African American students). Statistics from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, 2008) show that for 2005–2006 high school dropout rates are highest for American Indians/ Alaska Natives (6.9% of the total students in this ethnic group), followed by African Americans (6.3%), Hispanics (5.8%), Whites (2.6%), and Asian/Pacific Islanders (2.4%). The discrepancies in these figures illustrate the importance of ensuring that children who speak devalued dialects and languages are assessed fairly and at the same time have access to learning opportunities through necessary and relevant support.

Language and Literacy Ideologies

The problematic situation for linguistic minorities in U.S. school systems clearly goes beyond language-related issues (e.g., a policy that bases school funding on local taxes, which results in a dramatically unequal allocation of resources for schools). Language differences, and particularly language ideologies about such differences, nevertheless play a crucial role in the differential achievement of various populations. We argue that a large part of this problem is that educational policies are formed on the basis of “conventional wisdom” informed by language and literacy ideologies, rather than by research-based knowledge. We use the term language [and literacy] ideology to mean widely-shared beliefs about language and literacy that organize social relations. These ideologies are particularly damaging because they seem to be “commonsense” notions about, for example, what is good, bad, elegant, or impoverished language, simultaneously placing the speakers of such labeled language into hierarchical social relations (Woolard, 1998). Speakers whose language is deemed prestigious are placed higher in social status than those whose language is deemed inadequate or full of “error.” Thus although all dialects of English have been shown scientifically to be fully formed, systematic, and adequate, even elegant, linguistic systems, dominant language ideology in the U.S., expressed in “conventional wisdom,” devalues vernacular dialects (of all languages) by considering them sloppy or badly-formed. We explore three such ideologies here: the ideology of language standardization, the ideology of language purism, and the ideology of monolingualism, showing how each of these ideologies contradicts research results regarding actual linguistic realities.

First, what is referred to as “standard” English exists more as an abstract concept than as an actual (spoken) variety of English. As already noted, it is defined more easily by what it lacks (e.g., socially stigmatized phonological or syntactic features) than by the presence of particular features. Moreover, the concept of a standard is viable only when applied to written, not spoken, language (Milroy & Milroy, 2003). The standardization of (written) English occurred over several centuries in England, beginning with the advent of print in the fifteenth century, becoming the established official language by about 1700, and continuing to adopt fine points of usage (e.g., different from rather than different than) as defined by the lexicographer Samuel Johnson and various published grammarians. All these eighteenth-century efforts at codification, however, impacted only the written language: although the notion of a standard was adhered to in writing, people continued to use various dialects for daily speech (as they still do). A significant outcome of the eighteenth-century codification efforts, however, was an ideology of standardization, that is, a belief in a superior uniform standard language that was accepted by virtually all speakers (Milroy and Milroy, 2003; Agha, 2003). This language ideology continues today, in both the U.S. and England, in spite of the documented reality of many “Englishes,” both global and local.

A second ideology, language purism, is closely related to the ideology of standardization. Not only is there a widespread belief in the existence of a uniform standard, but this standard is believed to be superior to all other varieties, both cognitively and linguistically. This belief persists despite the fact that numerous linguistic studies have shown clearly that all varieties in use are complex and regularly patterned linguistic systems, and that none of them are superior or inferior to any other....