1

From Markets to Social Learning

Mapping the Dynamics of Design, Use, and Early Evolution of New Technology

Several disciplines have generated research and theory that provide insight for managing relations between designers and users in developing new technology. The list grows significantly shorter, however, when the aim is, as for us here in this chapter, to find frameworks that would provide integrative yet also usefully nuanced insight on matters comprising developer–user relations. The inquiry into the integrative theories of developer–user relations is organized as follows. We first examine two long-standing strands of research, which specifically focus on the engagement of users in innovation: “participatory design movement” and “user-innovation research.” Both these strands of research are key to understanding the users’ direct involvement and innovativeness in technology development, yet they remain somewhat narrow for the scope of issues the present volume is concerned with. We hence turn to B.-Å. Lundvall’s “learning economy,” which is a commonly used point of departure in innovation studies and policy. While we broadly agree with the learning economy’s ideas, we come to find Lundvall’s framework paradoxical; it raises interaction and learning between producers and users to the fore, yet fails to address the substantial variations and dynamics in how these play out. To address these key issues we turn to the social learning in technological innovation (SLTI) framework, which addresses these matters more fully. At the end we spell out an agenda how the present volume seeks to take the SLTI further.

PUTTING USERS’ INNOVATIVENESS ON THE MAP: PARTICIPATORY DESIGN AND USER-INNOVATION RESEARCH

The participatory design movement (PD) has been in many respects a forerunner in the co-design of novel technologies with end users and implicated users. Emerging out of the realization that workers and trade unions were not able to negotiate good design of work in the way they had been able to negotiate pay bargains, early PD was primarily concerned with satisfactory work life as a source of well-being and productivity. Workers’ participation in technology design was seen as a means to counter negative effects (reductions of workforce, de-skilling, and reduction of the quality of working life) that management-deployed technologies could introduce (Bjerknes et al. 1987; Bansler 1989).

The interests of management and different groups of workers were regarded to be adversarial, per se (Ehn 1993; Bansler 1989), resulting in an array of measures to balance the situation. Efforts were made to come to an agreement with management about the project, and its objectives and long-term maintenance. Designers aligned themselves purposefully with the users and took it upon themselves to acquire an in-depth understanding of the work practices involved (Bødker et al. 1987; Törpel et al. 2009; Bjerknes and Bratteteig 1987). All the affected worker groups were to be represented in the design process and emphasis was laid on ensuring that all the participants had an opportunity to express their points of view. Specific tools and arrangements were developed to provide the workers with means to understand the design process and have a true impact on it. The idea was that these tools would have to be relevant to workers’ actual experiences and allow them to comment on the details of the design and envision how they would influence the work (Ehn 1993; Schuler and Namioka 1993). Implicitly, the emphasis was laid on ensuring democratic processes within the design project, even though the prime threats were seen to arise from the society-wide political asymmetries.

Since the 1970s and 1980s PD has proliferated beyond its original contexts. The borders between participatory and other collaborative design projects (e.g., in open source software development and user-centered design) have become increasingly blurred. Methods and procedures originating from PD have become commonplace tools for the mainstream software design and industry, including major techniques such as collaborative prototyping, use of ethnographic methods for design, prefilled joint inquiry forms, “soft” work and system modeling, et cetera. This development coincided with workplace-specific information systems giving way to increasingly generic and packaged products developed for wider clientele, rise of PD-oriented projects done by companies as well as vaning of trade union power and their interest in new technology (Voss et al. 2009a).

In the midst of these changes, the collective resource approach and most of its descendants (for reviews see Bansler 1989; Kensing and Blomberg 1998; Hirschheim and Klein 1989) remained focused on articulating how technology should be developed more democratically and how this could be realized in development projects, rather than mapping out all the empirical issues involved in development–use relations. In regards to this latter concern the most formidable integrative frameworks around participatory design movement appear to be those that combine its accumulated insights with research in science and technology studies (e.g., Suchman et al. 1999; Suchman 2002; Voss et al. 2009a; Hartswood et al. 2002). Out of these, we shall discuss in detail in the following the SLTI framework (Sorensen 1996; Williams et al. 2005), which broadens the extant participatory and user-centered design frameworks to better account for the increasingly multifaceted and dynamic constellations and practices that comprise developer–user relations.

The case is somewhat similar with the pioneering line of research on user-innovation led by Eric von Hippel and others. Since the mid-1970s it has focused on verifying the amount of inventions made by users, identifying the users that are likely to innovate, why and where users innovate, and the makeup of user-innovation communities. In striking contrast to the assumptions in the traditional linear model of innovation, 19 to 36 percent of users of industrial products (von Hippel 1988; Herstatt and von Hippel 1992; Morrison et al. 2000; von Hippel 2005) and 10 to 38 percent of consumer products (Luthje and Herstatt 2004; Franke and Shah 2003; Luthje et al. 2005) have been shown to develop or significantly modify products. The approach is best known for its work in identifying and working with lead-users, users that are most likely to be ahead of market trends and innovate products that appeal to the rest of the user-base and their work on open source and other user-innovation communities and various innovation toolkits to facilitate shifting inventive activities to users (Luthje and Herstatt 2004; von Hippel 1988, 2001; von Hippel and Katz 2002; Luthje et al. 2005). In affinity to PD this research has shown that corporate R&D labs are by no means the only, necessary, or in many domains even the primary sources of invention (von Hippel 2005).

This line of research has also examined information asymmetries between developers and users, characteristics of “user-innovation niches” and effects of “sticky information,” information that is difficult to detach from its domain of origin, in the interchange and learning between manufacturers and users both after the market launch and in problem identification (Luthje and Herstatt 2004; Tyre and von Hippel 1997; von Hippel 2005; Lettl et al. 2006). In so doing, the research has moved beyond inventions by users, and, as one of the latest steps, inquired into the pathways traversed when user-innovations are transformed into commercial products, and the effects user-innovation has on industry development in the longer haul (Baldwin et al. 2006; Hienerth 2006). However, this research tradition offers an empirical and theoretical framework for studying and understanding user-driven innovation, rather than provides an integrative framework to the range of issues that comprise the relevant behaviors in development–use relations. Put in other words, both PD and “user-innovation research” have focused on perhaps the most interesting and radical forms of user involvement in innovation, rather than seeking to extensively cover the constituents, relations, and dynamic interplay that comprise the developer–user nexus, including the cases where users’ influence to development is restricted to phases after the initial market launch of new technology (Voss et al. 2009a).

Where then to turn? We could, of course, ask: isn’t the underlying theoretical framework in user-innovation research economics and in the early PD Marxist political economy? In that case, shouldn’t economics be regarded as discipline that provides, or at least should provide an encompassing framework for the range of issues in how production and consumption relate? As this position is widely held, particularly among economists, let us move to the debate and frameworks for producer–user relations within economics.

INTEGRATIVE FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPMENT–USE RELATIONS: FROM THE INVISIBLE HAND TO ORGANIZED MARKETS …

While economics is the one discipline focused on the question of how supply and demand relate, its traditional means of analysis, data-sets, and models become less obvious when the focus is shifted from relatively stable classes of products and relatively stabilized patterns of consumption to products that are just emerging (Freeman 1994; Rosenberg 1982; Fagerberg 2003). Such products often do not as yet have a clear market or direct competitors, but instead try to establish a new category of goods amongst potential buyers and users and regulators (Green 1993; Callon et al. 2002). When perspective is further shifted from production and purchase to designing and using—elongating both ends of market relation so as to include what gets to be produced and why something gets purchased—the scope of appropriate questions and thus the appropriate framework become further complicated. Indeed, a persisting feature of innovation studies and institutional economics is the critique of neoclassical economics on its difficulties in dealing with technological change and the associated economic growth (Freeman 1994; Fagerberg 2003). Here B.-Å. Lundvall’s argumentation largely converges with our view.

Lundvall asserts that in standard microeconomics:

Both producers and users would thus operate under extreme uncertainty without the qualitative information about the preferences and needs of users or the values that a new product would offer in practice.

For an opportunistic actor involved in an innovative quest it appears rather post-festum to accept that demand becomes visible once the new product is in the market, and the good will find its correct price and volume of production. Nonetheless, there is a range of preparations and precautions one meets in standard editions on marketing and entrepreneurship that comply with assuming that only a black box of “markets” exists as a mediating mechanism between actors in the supply and demand side of a given line of products (Proctor 2000; Kotler and Armstrong 2004; Malhotra and Birks 2003). Yet high uncertainty over the fate of novelties would arguably favor incremental product variations as well as favor products that can be scaled to large series in case they meet up with high demand; not least to compensate for the likely array of failures. We can debate if in such a view it makes sense at all to develop products for relatively small niche markets or to complex user practices requiring in-depth qualitative information on user’s needs and preferences (which is the case with most health technologies), but it is clear that actors involved with this kind of an innovative quest would receive little support in terms of how to proceed with it.

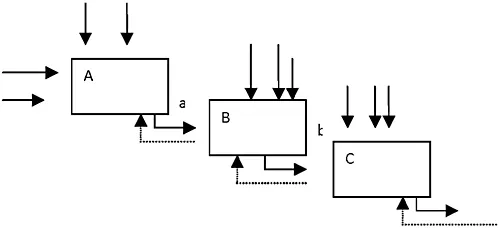

Indeed, Lundvall’s own work on producer–user interaction reveals that in many sectors producers and users do not leave themselves at the mercy of markets, but, instead, develop sustained relations that allow the exchange of qualitative information related to user’s needs and technological possibilities. The resultant form of producer–user relation has been characterized as “organized markets,” where a producer develops sustained a relationship with one or several selected user organizations and vice versa (Lundvall 1985, 1988). The minimal unit of an organized market can be depicted in a stylized manner as two dyads of producers and users as in Figure 1.1.

In such niche markets innovations targeted to external users (product innovations) are frequent (Pavitt 1984), implying that in-depth information sharing does not lead to integrating the user or producer into a hierarchical relationship. Diversification of skills, for instance, to medical electronics and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, is also a substantial reason for nonintegration. Organizations have to make considerable investments to build and sustain competitive skills, knowledge, machinery, marketing, and delivery mechanisms. This reduces their opportunistic desire to expand their business up- or downstream, even in a case when a particular innovation makes such moves potentially profitable (Freeman 1994). Integrating two levels of production would also make the actor compete directly with other users, turning into a less preferable business partner for them (Lundvall 1985). Organized markets also lower producers’ marketing costs and, for users, lessen transaction costs in finding suitable and reliable resource providers. They also lessen further agency costs: (a) costs incurred to monitor the agent to ensure that it (or he or she) follows the interests of the principal, (b) the cost incurred by the agent to commit itself not to act against the principal’s interest (the “bonding cost”), and (c) costs associated with an outcome that does not fully serve the interests of the user (von Hippel 2005, 6, 46–52). These findings are particularly relevant for health technologies, which tend to be used in highly specialized contexts and by highly specialized people.

The result of these considerations is, in Lundvall’s words, a “focus upon a process of learning, permanently changing amount and kind of information at the disposal of actors … we shall focus upon the systemic interdependence between formally independent economic subjects” (Lundvall 1988, 350; emphasis in original). The most examined kind of learning Lundvall refers to is “learning-by-doing,” which was originally offered to explain why the cost o...