![]()

PART I

COGNITIVE

DEVELOPMENT

Cognitive development is the development of knowledge and inference. In adolescence and beyond this includes the development of advanced forms and levels of thinking, reasoning, and rationality. We begin with Piaget’s conception of cognitive maturity as formal operations. From there we proceed to diverse aspects and conceptions of advanced cognition and development. As we will see, current research and theory are consistent with Piaget’s conception of cognitive development as a rational process with rational outcomes but challenge his depiction of cognitive development as a single universal sequence of general structures leading to a highest, and thus final, stage.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Piaget’s Theory of

Formal Operations

To be formal, deduction must detach itself from reality and take up its stand upon the plane of the purely possible.

—Jean Piaget

(1928/1972b, p. 71)

Developmental psychologists are quick to talk about matters such as emotional development, social development, personality development, and cognitive development. Because most people share the notion that children develop toward maturity, such terminology may be uncritically accepted. As discussed in the Introduction, however, psychological maturity is a more problematical notion than physical maturity. This raises questions about what we mean by psychological development.

Caution is in order, for example, regarding any claim that certain emotions are better than others. But what, then, is meant by emotional development? Similarly, on what basis are some social interactions, personalities, or thoughts deemed more advanced or mature than others? Are we deluding ourselves when we refer to social development, personality development, and cognitive development?

Although such questions are reasonable and important, I believe the issues they raise can be satisfactorily addressed. In this chapter, focusing on cognitive development, I present the theory of Jean Piaget, who believed that cognition is indeed a developmental phenomenon (Müller, Carpendale, & Smith, 2009). Piaget attempted to demonstrate that over the course of childhood and early adolescence, individuals actively construct qualitatively new structures of knowledge and reasoning and that the most fundamental such changes are progressive in the sense that later cognitive structures represent higher levels of rationality than earlier ones.

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Imagine a small pet store in which there are 10 animals for sale—6 dogs and 4 cats. If asked whether there are more dogs or cats in the store, you would immediately respond that there are more dogs. Suppose, however, you are asked whether there are more dogs or more cats in a pet store you have never seen on the next block. You would indicate that, without more information, you simply don’t know.

Suppose now you are asked whether there are more dogs or more animals in the original store. This might seem a peculiar question. After clarifying that you have understood it correctly, however, you would respond that there are more animals. If asked whether there are more dogs or animals in the store on the next block, you would indicate that it has at least as many animals as dogs. You would not need any additional information about the other store to reach this conclusion: Knowing that dogs are animals, it follows as a matter of logical necessity that any pet store must have at least as many animals as dogs.

Imagine that a preschool child is brought into the original pet store and is asked the same questions. It might turn out that she is unfamiliar with dogs or cats or that she has trouble telling them apart. It is also possible that the numbers involved here exceed her counting skills. Alternatively, she might come from a cultural background where dogs and cats are not classified together as animals. For a variety of reasons of this sort, a child might fail to provide satisfactory answers to the questions you had been asked. This would provide little basis for questioning her rationality, however. We would simply note that for reasons relating to her individual or cultural background, she has not learned certain things that are eventually learned by all normal individuals in our culture.

Suppose, however, that the child is indeed familiar with dogs and cats, is able to distinguish and count them, and understands that all dogs and cats are animals. When asked whether there are more dogs or cats, she responds correctly that there are more dogs. When asked about the store on the next block, she responds correctly that without going there to see, she cannot know whether it has more dogs or cats.

You then ask whether there are more dogs or animals in the store she is in, repeating the question to make sure she understands it. She responds that there are more dogs. You ask why, and she notes that there are six dogs and only four cats. When you ask about the store on the next block, she responds that without further information, she cannot know whether it has more dogs or animals. Just to be sure, you ask whether dogs are animals. “Of course,” she says.

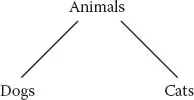

What is going on here? A plausible account is that the child does not understand the nature and logic of hierarchical classification. She knows that dogs are animals and that cats are animals, but she does not fully grasp that any given dog is simultaneously a member of the class of dogs and of the class of animals (see Figure 1.1). Thus she does not realize that in any situation, the class of animals must have at least as many members as the class of dogs. When asked to compare dogs with animals (two different levels in the class hierarchy), she ends up comparing dogs with cats (which are at the same level in the class hierarchy) and concludes there are more dogs. In other words, she is not ignorant of relevant facts about dogs, cats, and animals, and she is not deficient in particular arithmetic skills. What she apparently lacks is abstract conceptual knowledge about the nature of hierarchical classes.

Figure 1.1 Hierarchical classification.

Logical understandings of this sort were the main focus of interest for the renowned Swiss developmentalist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). In numerous studies over many decades, Piaget and his collaborators found that preschool children routinely show patterns of reasoning qualitatively different from those of older children and adults. Moreover, the later forms of reasoning and understanding were demonstrably more coherent and adaptive. Piaget did not deny that children learn new facts and skills as they grow older and that there is thus a quantitative growth of knowledge. He suggested, however, that qualitative shifts in the nature of reasoning are more fundamental. It is these that represent progress toward higher levels of rationality. What accounts for such changes, he wondered.

One possibility is that sophisticated cognitive structures are learned from one’s environment. There is no evidence, however, that logical knowledge of the sort Piaget studied is taught to young children or that direct teaching of logical facts or procedures has much effect on their thinking. An empiricist view has difficulty accounting for the relatively early and universal attainment of basic logical conceptions.

Another possibility is that the rational basis for cognition is innate, emerging as a result of genetic programming. But there is no evidence that we inherit genes for logic and little reason to believe that genes containing the sorts of logical understandings just discussed could be generated by the process of evolution. A nativist view turns out to be no more plausible than an empiricist view.

Constructivism

On the basis of such considerations, Piaget suggested that rational cognition is constructed in the course of interaction with the environment (Campbell & Bickhard, 1986; Moshman, 1994, 1998; Müller et al., 2009). Although this does not rule out a substantial degree of genetic and environmental influence, it emphasizes the active role of the individual in creating his or her own knowledge.

One might wonder, however, why individual construction would enhance rationality. If we all construct our own cognitive structures, why doesn’t each of us end up with a unique form of cognition, no more or less justifiable than anyone else’s? Why does individual construction lead to higher levels, and universal forms, of rationality?

Equilibration

Piaget suggested that rationality, which he construed largely as a matter of logical coherence, resides in corresponding forms of psychological equilibrium. People relate to their environments by assimilating aspects of those environments to their cognitive structures. If their current structures are adequate, they can accommodate to the matter at hand. If this cannot be done, however, the individual may experience a state of disequilibrium. New cognitive structures must be constructed to resolve the problem and restore equilibrium. Piaget (1985) referred to this process as equilibration.

Consider, for example, the child in the pet store. When asked to compare dogs with cats, she assimilates this request to her cognitive schemes of grouping and counting. Accommodating to the specifics of the situation, she concludes that there are more dogs. When asked to compare dogs with animals, however, she makes the same assimilation. Grouping the dogs together leaves the cats, whereupon she compares dogs with cats and concludes that there are more dogs. Not realizing that she has failed to answer the intended question, she may remain in equilibrium.

Suppose, however, that you now ask her to divide the dogs from the animals. And perhaps you throw in a few questions encouraging her to explain and justify what she is doing. In the course of the resulting interchange, she may realize that the dogs fit in both categories. This may create a sense of disequilibrium, leading her to vaguely recognize a problem with her approach to the matter. Reflecting on the nature of her classification activities, she may construct a more logically coherent scheme of hierarchical classification that will enable her to make sense of the situation and restore equilibrium.

Notice that the new classification scheme is constructed in the course of interaction with the physical and social environment but is not internalized from that environment. Thus it is neither innate nor (in the usual sense) acquired.

Notice also that the new equilibrium derives from a more advanced cognitive structure that in some sense transcends the child’s earlier ones. Equilibration, in other words, leads not just to different structures but to better ones. Thus Piaget’s conception of construction via equilibration suggests that cognitive changes, rather than being arbitrary and idiosyncratic, show a natural tendency to move in the direction of greater rationality. Piagetian constructivism is a form of what I later refer to as rational constructivism.

Research since the 1970s has refuted a number of Piaget’s specific interpretations and hypotheses and has raised serious questions about various aspects of his account of development (Karmiloff-Smith, 1992; Moshman, 1998). There is substantial agreement, however, with his most general claim: Children actively construct increasingly rational forms of cognition, thus it is meaningful to speak of cognitive development.

The question for adolescent psychology is whether such development continues into adolescence. Piaget’s own view was that early adolescence marks the emergence of the final stage of cognitive development—formal operations.

Piaget’s Theory of Formal Operations

The child of age 9 or 10, in Piaget’s theory, has attained and consolidated a stage of cognition known as concrete operations (Inhelder & Piaget, 1964). The concrete thinker, according to Piaget, is a logical and systematic thinker who can transcend misleading appearances by coordinating multiple aspects of a situation. She or he understands the logic of classes, relations, and numbers and routinely makes proper inferences on the basis of coherent conceptual frameworks. Research since the 1960s has substantially confirmed this picture of early rationality, suggesting that, if anything, children show various forms of sophisticated reasoning and understanding even earlier than Piaget indicated (Case, 1998; DeLoache, Miller, & Pierroutsakos, 1998; Flavell, Green, & Flavell, 2002; Gelman & Williams, 1998; Karmiloff-Smith, 1992; Wellman & Gelman, 1998).

Piaget believed, however, that adolescents construct a cognitive structure that incorporates and extends concrete operations. He referred to this more advanced form of rationality as formal operations and suggested, on the basis of research by his colleague Bärbel Inhelder, that it begins to develop at approximately age 11 or 12 and is complete and consolidated by about age 14 or 15 (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). Central to his conception of formal operations is the cognitive role of possibilities.

Reality as a Subset of Possibilities

Children begin considering possibilities at very early ages (Piaget, 1987). The imaginative play of the preschool child, for example, explores a variety of possible characters, roles, and social interactions. For children, however (in Piaget’s view), possibilities are always relatively direct extensions of reality. The real world lies at the center of intellectual activity. Possibilities are conceived and evaluated in relation to that reality.

For the formal operational thinker, on the other hand, possibilities take on a life of their own. They are purposely and systematically formulated as a routine part of cognition. Reality is understood and evaluated as the realization of a particular possibility.

Consider, for example, gender role arrangements. In every culture, children learn what are deemed proper roles for males and females. In a culture where women in medicine are expected to be nurses, not physicians, for example, a young child might think about a girl becoming a surgeon but would evaluate this possibility with respect to the actual gender role arrangements of the culture and likely see it as amusing, bizarre, or inappropriate.

A formal operational thinker, on the other hand, would be able to imagine a wide variety of gender role arrangements. The actual arrangements of his or her society, then, would come to be seen as the realization of one of many pos...