Vienna Fin-de-siècle: Between Artistic City Planning and Unlimited Metropolis

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani

In May 1889 in one of Vienna’s publishing houses an inconspicuous little book with an elaborate title appeared, Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerichen Grundsätzen (City Planning According to its Artistic Principles). The book had an even more complex subtitle, Ein Betrag zur Lösung Modernster Fragen der Architektur und monumentalen Plastik unter besondered Beziehung auf Wien (Contribution for solving the modern questions of architecture and monumental art with special reference to Vienna).1 The author was Camillo Sitte, architect, and, at the time of the publication, director of the State School of Applied Arts in Vienna. He explained in his own introductory remarks why he undertook the writing of the manuscript:

It seemed appropriate, then, to examine a number of lovely old squares and whole urban layouts – seeking out the bases of their beauty, in the hope that if properly understood these would constitute a compilation of principles which, when followed, would lead to similar admirable effects. In keeping with this intention, the present work is to be neither a history of town planning nor a polemical tract, but instead will offer study materials and theoretical deductions for the expert. It will form a part of our vast intellectual edifice of practical aesthetics; for the professional city planner, it may prove to be a useful contribution to that fund of experience and rules on which he depends in drawing up his plans for the parcelling of land.2

Coming after an already long and prestigious career, Der Städtebau almost appeared like an isolated outburst, even though a second volume should have followed, Der StädteBau nach seinen wirtschaftlichen und sozialen Grundsätzen (City Planning by taking into account its economic and social principles). Indeed, the book was hardly based on his previous writings (of which only two were incidentally dealing with city building), but rather on prior impressions and experiences. Sitte processed these long delayed considerations almost in an explosion-like manner; the entire book was planned and written in about seventeen nights.

The small book ran quickly out of stock. The publishing house started printing many new editions and translations of this first bestseller of the theory of city planning.3 Meanwhile the author of the manuscript was hardly the sovereign protagonist of the architectural and city planning culture, which we could surmise him to be after the immense success of his book. Sitte’s architectural designs moved in line with the general historicism that dominated architectural practice at the turn of the century in Vienna, and they were by no means better than average. If anything his urban planning projects were considerable, but outside Vienna. From the 1890’s, thanks to the reputation he earned for his book, Sitte was commissioned to develop a series of planning schemes for small and medium cities in Bohemia and Moravia. In addition he lectured frequently and wrote sedulously for daily newspapers and technical magazines.

City architecture for the lost flâneur

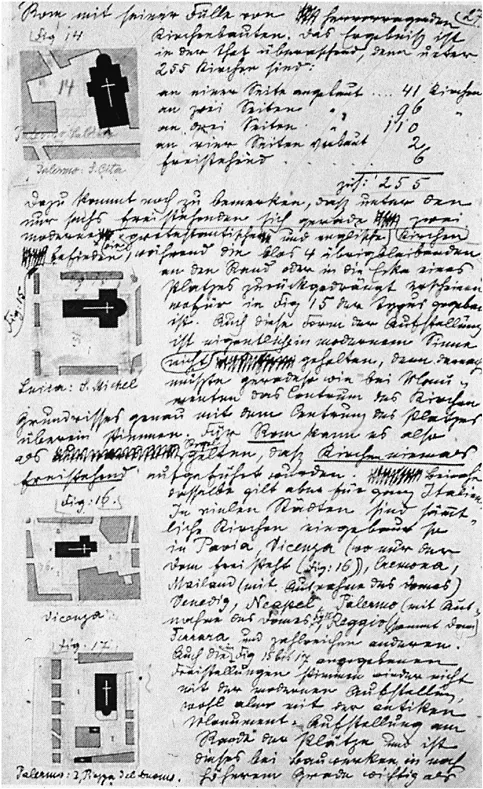

Der Städtebau goes about the exploration of the past in order to derive maxims for the present. In fact, Sitte’s book is divided in two sections: one analytic and one synthetic. In the first section, “beautiful” city structures from Western Europe and above all from Italy were carefully studied. The author obviously knew almost all of them, because they were the destinations of prolonged and repeated study trips. Sitte always proceeded with the same method: he arrived at the city, was driven from the railway station to the main square, asked for the hotel with the best restaurant, the best bookstore, and the best watchtower. He ascended the tower and from there analyzed the ground plan of the city, which he later sketched in an abridged version during dinner. In contrast, in the second section, he went on to criticize contemporary city planning methods in consideration of the “lessons of the old masters,” and he issued suggestions for their improvement.

The fact that most of Sitte’s selected exemplars came from the Middle Ages did not make him a neo-medievalist, like John Ruskin was two generations before him. Besides squares or series of squares like those of Siena or Lucca, the author analyzed spatial situations of cities from the Renaissance and Baroque eras, and even from the nineteenth century. The idealization and imitation of a certain epoch was not suggested; the concept was rather to “distil” or refine the universal, historically invariable rules of composition for urban planning that could and must serve the present.

Sitte’s contemporaries Heinrich Wölfflin and Alois Riegl shared a similar approach on the role of history. The two influential art historians also searched for principles valid for all styles and epochs. Thereby they admittedly (and inevitably) assumed the perspective of their epoch, that one would find in the past what is dear to the heart. In a similar way, the allegedly objective method of work used by Sitte proved to have remarkably headstrong results – though the premises with which he supported his examinations were downright subjective. The Viennese culture historian, painter, architect and city building theoretician felt uncomfortable in large, undivided places and in wide, axial placed streets with unobstructed views. He needed narrow, confined, homey spaces, and limited sights; otherwise he felt pushed, like the protection-seeking figures in Edvard Munch’s paintings, against the walls of the streets and squares. His ideal of urban beauty was late-impressionist: constantly changing scenes were put together in sequences, almost kaleidoscopically. These scenarios were always related to the spectator and his changing location – but also his changing mood and state of mind. They coalesced into a picturesque experience of movement in space.

Sitte readied himself to fathom the past with these unambiguous preferences and idiosyncrasies – supposedly in order to learn from it, but, in truth, he wanted it to confirm his theory. With the help of his scientific analysis his system was clear from the beginning: it was based upon the concept of constructions optically connected, narrow and winding streets with new views, confined squares with long-running closed walls, asymmetrically arranged monuments and clear centres, to which other groups of spaces or sequences of spaces should be attached.

Sitte looked for all of these aspects in historical exemplars, but he selected the history accordingly. His study trips led him exclusively to places, where he felt comfortable. He studied exclusively the urban situations, which gave him such well-being. In a way, these became more psychological than art historical. Again and again, an ominous observer was called to witness. What does he or she see? Does he or she like what they see? What does he or she feel? A flâneur was appointed judge of the beauty of the city, but he is not the flâneur of Charles Baudelaire, who gets lost in the perspectival space of the grandiose Parisian boulevards and passages, or Edgar Allan Poe’s Man of the Crowd who is merged in the unmanageable big-city-crowd at the heart of London.4 It is a flâneur, who could rather be a modern descendant of Joseph von Eichendorff – solitariness loving, quiet and shy, always focused on security and a bordered picturesque panoramic view.5 It is, obviously, none other than Camillo Sitte himself.

This did not make Sitte a worldly dreamer. It was clear to him that “modern living as well as modern building techniques no longer permit the faithful imitations of old cityscapes, a fact which cannot be overlooked without falling prey to barren fantasies.”6 He unsparingly described the changed circumstances:

The life of the common people has for centuries been steadily withdrawing from public squares, and especially so in recent times. Owing to this, a substantial part of the erstwhile significance of squares has been lost, and it becomes quite understandable why the appreciation of beautiful plaza design has decreased so markedly among the broad mass of citizenry. Life in former times was, after all, decidedly more favourable to an artistic development of city building than is our mathematically precise modern life, in which the human being himself becomes a machine. … Above all, the cities are growing with giant dimensions that disrupt the older artistic forms. The larger the city, the bigger and wider the streets and squares become, the higher and bulkier are all buildings, until their dimensions, what with their numerous floors and interminable rows of windows, can hardly be more organized any more in an artistically effective manner. […] As this cannot be altered, the city planner must, like the architect, invent a scale appropriate for the modern city of millions.7

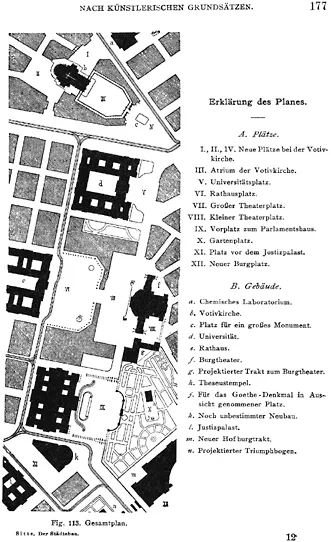

2.2 Camillo Sitte. Project for the reconfiguration of the Ringstraße

Source: From Camillo Sitte, Der Städtebau nach seinen Künstlerischen Grundsätzen, Vienna, 1889

Unquestionably, Camillo Sitte’s text was incredibly rich and full of perspectives on urban design and interpretations of historic urban places in light of the contemporary trends in early city planning. Yet, Sitte’s statements related to “the modern city of millions” and many other considerations on the practical requirements of modern planning have mostly been overlooked or simply ignored both by his detractors and his admirers. For over a century, readers and critics of the book have searched and drawn ideas and excerpts to reinforce their own a-priori positions – positive or negative – rather than understand the entire theory and attempt to give it a specific form. Sitte himself was more a theoretician than a full-fledged practitioner; his burgeoning urbanistic career was quickly interrupted by his untimely death. Had he lived longer, it is unlikely that he would have given us a comprehensive image of his “modern city of millions,” as he appeared content operating as a pragmatic designer whose work would reflect the specifics of history, site, and context.

On the contrary, his great rival, Otto Wagner, boldly addressed the daunting challenge to design the modern city of millions. The rationality and geometry of his utopian drawings of Vienna as a City of Unlimited Growth became a synonym of modernity like Le ...