eBook - ePub

On the Town in New York

The Landmark History of Eating, Drinking, and Entertainments from the American Revolution to the Food Revolution

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On the Town in New York

The Landmark History of Eating, Drinking, and Entertainments from the American Revolution to the Food Revolution

About this book

This delightful, vividly detailed book takes you out on the town in New York from the American Revolution to today's Food Revolution. Michael and Ariane Batterberry, founders of Food and Wine magazine, detail a magnificent journey through the streets of New York, exploring the customs in eating, drinking and entertainment of both high and low culture. They take you into the dives of the Tenderloin and to the elaborate banquets of the Gilded Age. Whether they are talking about a saloon or the famous Astor House, they provide the most fascinating details from New York's richly diverse culinary history. First published in 1973 when New York seemed to be a city in decline, the original edition of On the Town in New York saw very little hope in the city's culinary future. Who could have known that New York was on the brink of a Food Revolution and a total reinvention of the American dining experience? Conceived to redress that miscalculation and to celebrate the thriving growth of dining out in New York, this anniversary edition of On the Town in New York contains a new afterward that picks up where the Batterberrys left off. All of the wonderful details of the original edition remain. We still find the vivid picture of the reception for Lafayette in 1824, the interesting birth of the cafeteria, as well as the description of an 1897 costume ball that cost $350,000. Even the recipe for the Algonquin's Famous Apple Pie is here for the traditionalists. What's new is the interesting tale of how New York came to be the restaurant capital of the world at a time when no one thought it possible. The Batterberrys combine their keen sense of New York's social history with their insider's knowledge of how the food and beverage industry reconceptualized itself to take advantage of the changing social fabric following the turbulent 60s. Here we find details of how the changing role of women, the influx of new immigrant communities, and the focus on nouvelle cuisine combined in unique ways to create a thriving dining industry rich in talent and celebrity. Delicious and irrisistable, this social history of New York will please anyone whose tasted the specialties of Chinatown, had a steak at Keen's or basked in the luxuries of the Rainbow Room.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On the Town in New York by Michael Batterberry,Ariane Batterberry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

1776-1800

Little Birds are choking

Baronets with bun,

Taught to fire a gun:

Taught, I say, to splinter

Salmon in the winter—

Merely for the fun.

Baronets with bun,

Taught to fire a gun:

Taught, I say, to splinter

Salmon in the winter—

Merely for the fun.

Lewis Carroll

There is nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced, as by a good tavern or inn.

SAMUEL JOHNSON

American history books do little to describe the plight of New York City during the Revolution for the simple reason that it was an enemy base. Washington prepared to defend Manhattan early in January of 1776, and within a month fully a quarter of the panicked residents had fled. By August, Staten Island and New York harbor were in the clutches of a monster army of thirty-two thousand redcoats under the command of two brothers, Admiral the Right Honorable Richard, Lord Vincent Howe, of the Kingdom of Ireland, more commonly known as "Black Dick," and General William Howe, who, but for his dark eyes, so closely resembled Washington that he could be mistaken for him at a distance. Washington's eighteen thousand inadequately trained troops were no match for this, the largest expeditionary force in British history, and in September the British were able to land unimpeded at Kip's Bay as the last of the revolutionaries retreated to Harlem and then to Westchester. For the duration of the war such patriots as there were in the vicinity lurked in the north, descending into New York for an occasional raid.

The British marched into a ghost town of about four thousand buildings, a thousand of which were swept away within a month by a mysterious fire. But soon the city took on the character of a wartime capital as the deserted houses became crammed with soldiers, officers and their families, and refugee Tories of all classes from all thirteen colonies.

Meanwhile captured revolutionaries, the only men of patriotic persuasion on Manhattan, were crushed into squalid jails or rotting prison ships anchored in the East River. New York settled down to seven years of something like the life of an eighteenth-century siege town, with the horrors of crowded quarters, black markets, disease, and cold, offset by the glamor of military assemblies, dress uniforms, and the general suspense of war.

The Tory tavernkeepers, those who had remained behind or emigrated to the city, made a fortune serving the heavy-drinking English. And it is important to remember that taverns were the local hotels, restaurants, and meeting houses of the eighteenth century. As competition became heated, a flurry of freshly painted shingles went up throughout the city, bearing such staunchly partisan legends as The Sign of Lord Cornwallis, The King's Arms, and The Prince of Wales. More impressed by the boom than by protestations of loyalty, the authorities proclaimed in Rivington's Royal Gazette on January 8, 1780, that "many evils daily arise from unlimited numbers of Taverns and Publick Houses within the City and its Precincts" and restricted licenses to two hundred, any of which would be immediately withdrawn "from such as shall be known to harbor any riotous or disorderly companies."

The more astute tavernkeepers, far from soliciting the company of the riotous and disorderly, posted advertisements for such entertainments as would theoretically appeal to tasteful young bloods straight from London.

John Kenzie, proprietor of Ranelagh Gardens, formerly of the Mason's Arms, offers dinners on the shortest notice, breakfast, relishes, etc. all the forenoon; tea, coffee, etc., all the afternoon; a band of music to attend every Saturday evening ... the best wines that can possibly be had in this city . . . and being a veteran in this Most Gracious Majesty's service, he shall hope for the Smiles, Protection, and Encouragement of the gentlemen of the army and navy as well as the Respectable Public. N.B. In the superb Garden there is the most elegant boxes [sic] prepared for the reception of the Ladies, and the most perfect enjoyment of the evening Air.

Precisely how superb Mr. Kenzie's Garden was is a matter for conjecture—almost every tree on Manhattan Island had long since been chopped down for firewood.

Despite the detached frivolity of New York wartime society, privation in the occupied city was appalling. For two winters the Hudson actually froze over. Shantytowns sprang up in the burnt-out sections, but even they could not house the destitute. Many of the Royalist refugees escaped to New York virtually penniless; the tavernkeepers rallied to their aid by organizing lotteries and playing host to theatrical benefits performed by British officers. No aid, however, was given to the American prisoners of war, who were freed in 1777 for lack of rations. Many were so debilitated by malnutrition that they fell dead in the streets of New York before they could reach the vessels that were to transport them to New Jersey. At one point potatoes sold for a guinea a bushel, and biscuits of oatmeal containing as little nourishment as ground straw were served to the British troops. Only the very rich could afford the black-market prices of produce brought in from outlying farms.

Taverns had food to offer at a healthy price, and their supply of drink was frequently and lavishly replenished by privateers and Tory traders. But what there was could not have been prepared in the style most British demanded, for Mr. Ephraim Smith "of London" announced that he would reopen his tavern in Water Street "at the desire of many gentlemen of the Royal Army and Navy to be a Steak and Chop House in the London Stile, much wanted in the City. The best of wines, punch, and draft porter, with steaks, chops and cutlets will be served every day from one o'clock til four." For some enigmatic reason Smith's good intentions mush have backfired. His landlord advertised within the year: "House to rent—No Tavern keeper need apply."

The senior sycophant of the Tory tavernkeepers, a Mr. Looseley, was proprietor of the King's Head tavern in Brooklyn Heights. A fatuous, fawning egomaniac, with unquenchable aplomb, he published his own Royalist Gazette, a conglomeration of loyalist editorials and advertisements for his tavern, in which he characteristically referred to himself in the third person. Looseley would tolerate no nonsense on the part of Washington and his men. On September 20,1780, he proclaimed in his paper: "The anniversary of the Coronation of our ever good and gracious King will be celebrated at Looseley's, 22nd instant. It is expected that no rebel will approach nearer than Flatbush Wood." When prose could no longer contain his fervor, he expressed himself in verse:

On June 20 a dinner exactly British, after which there is no doubt but that the song of "Oh! the Roast Beef of Olde England" will be sung with harmony and glee.

This notice gives to all who covet

Baiting the hull and dearly love it,

Tomorrow's very afternoon

At three or rather not so soon

A bull of magnitude and spirit

Will dare the dog's presuming merit.

Baiting the hull and dearly love it,

Tomorrow's very afternoon

At three or rather not so soon

A bull of magnitude and spirit

Will dare the dog's presuming merit.

Taurus is steel to the backbone

And canine cunning does disown

True British blood runs through his veins

And barking number he disdains

Sooner than knavish dogs shall rule

He'll prove himself a true John Bull.

And canine cunning does disown

True British blood runs through his veins

And barking number he disdains

Sooner than knavish dogs shall rule

He'll prove himself a true John Bull.

On May 29, 1782, he wrote: "On this Day firm reestablishment being given to Monarchy—Tyranny and its Republic are no more. Looseley the Boniface of Brooklyn Hall, will produce a dinner at three o'clock fit for a conquering Sovereign." An exceptional invitation considering the fact that Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown seven months before. Reality caught up with Looseley soon enough. On November 23, 1782, the following advertisement appeared, not in the Royalist Gazette: "Auction Sale at Looseley's Inn, Brooklyn Ferry. Paintings, Pictures, Pier Glasses, an organ, billiard table, twenty globe lamps, flag staff, etc. The Landlord intends for Nova Scotia immediately."

As the Peace of Paris was negotiated, many a Tory tavernkeeper joined Looseley in his flight north, while still others were "intending for England" or "intending for the Indies." The Boniface of Brooklyn Hall, in fact, dragged out his last days as the proprietor of an unsuccessful hotel at Port Roseway.

In May of 1783 Washington and Sir Guy Carlton made the final arrangements for the evacuation of the British Army and safe conduct for any remaining Tories. On November 25 the triumphant Americans marched down Broadway.

New Yorkers, who have always hated missing a party, rushed back to their ravaged city for a week-long victory celebration. Sam

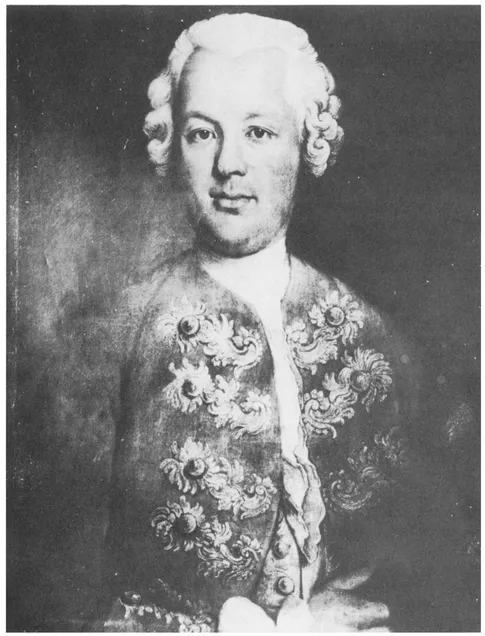

Sam Fraunces. Courtesy of the Sons of the Revolution.

Fraunces was asked by Governor Clinton to organize the first public dinner for Washington immediately following the march.

Fraunces, as Sam Francis styled himself after the Revolution, was a mulatto born in the French West Indies, and had served as proprietor of a New York tavern, the Mason's Arms, before 1763. In that year he became master of the establishment that made him famous, known before the war as the Queen's Head and situated in what had been the DeLancey mansion on the corner of Broad and Pearl streets. A dapper figure, he was, like most noted professional hosts, a connoisseur, an extrovert, and an autocrat. Above all, he was a sworn revolutionary. The Revolution itself was fomented in the urban "public houses" of the colonies, and it was at the Queen's Head that the Sons of Liberty and the Vigilance Committee met in 1774 to protest the landing of British tea and to lay plans for dumping it.

According to a popular Revolutionary poem by Philip Freneau, new York's foremost tavernkeeper had been among the first in the city to taste the wrath of the British:

Scarce a broadside was ended

'til another began again—

By Jove! It was nothing but

Fire away Flanagan!

At first we supposed it

was only a sham,

Til he drove a round-shot

thru the roof of Black Sam.

The town by their flashes

was fairly enlightened

The women miscarry'd, the beaus

were all frightened. . . .

'til another began again—

By Jove! It was nothing but

Fire away Flanagan!

At first we supposed it

was only a sham,

Til he drove a round-shot

thru the roof of Black Sam.

The town by their flashes

was fairly enlightened

The women miscarry'd, the beaus

were all frightened. . . .

Fraunces was kept a virtual prisoner on his own premises by the British during their occupation of New York, but managed to present a façade of such unruffled geniality that he was able to continue his anti-Royalist activities. For secretly aiding prisoners of war he was later awarded two thousand dollars by Congress "in consideration for singular services" and was appointed Steward to the President by Washington himself.

There is a tale that Frances' daughter, Phoebe, had afforded her country services no less singular than her father's. Unlucky Phoebe was serving as housekeeper at Washington's Richmond Hill headquarters when she fell in love with a young soldier named Thomas Hickey, a member of the commander's Personal Guard. Just before lunch one day she came upon her lover sprinkling poison over a dish of spring peas, a particular favorite of Washington's. Sworn to silence, Phoebe did as she was ordered and bore the dish to the dining table. But at the crucial moment honor prevailed and she snatched the lethal peas from beneath the general's nose and pitched them out the window. There, in the garden, they were pecked at by a neighbor's chickens, every one of which promptly fell dead, and the notorious "Hickey Plot" was exposed. Sam Fraunces' pride in his daughter's heroism must have been cold comfort to Phoebe when on June 28, 1776, Thomas Hickey was hanged at the corner of Bowery Lane and Grand streets, the first man to be executed for treason by the United States Army.

It could be said that in many ways the triumphal dinner organized by Fraunces in honor of General Washington was a climactic one. Paneled walls and pewter gleamed in the firelight and waiters in long white aprons scurried between the trestled tables refilling glasses and tankards as the company rose to the toast, "May a close Union of the States guard the Temple they have erected to Liberty." But the truly death-defying revel of the week took place on December 2, and was given, not surprisingly, by the French ambassador. His one hundred and twenty guests succeeded in dispatching one hundred and thirty-five bottles of Madeira, thirty-six bottles of port, sixty bottles of English beer, thirty bowls of punch, sixty wineglasses, and eight glass decanters. No further festivities were recorded for the next forty-eight hours.

On the morning of December 4, Washington's officers were told that their commander would leave the city for Mount Vernon that same day. At noon they hurried through the rain to Fraunces' Tavern, where Washington had arranged to meet them in the Long Room. After proposing a toast to his men, Washington embraced each of them in turn. Among those present were Generals Knox, Steuben, Schuyler, Gates, Putnam, Kosciuszko, and Hamilton, Governor Clinton, Major Fish, and Colonel Tallmadge, in whose Memories is an eye-witness report of the meeting:

Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I have never before witnessed, and I hope may never be called upon to witness again. . . .

But the time of separation had come, and waving his hand to his griev–ing children around him, he left the room and passing through a corps of light infantry, who were paraded to receive him, he walked silently on to Whitehall, where a barge was in waiting.

We all followed in mournful silence to the wharf, where a prodigious crowd had assembled to witness the departure of the man who, under God, had been the great agent in establishing the glory and independence of these United States.

As soon as he was seated, the barge put off into the river, and when out in the stream, our great and beloved General waved his hat, and bid us a silent adieu.

In 1784, New York City became the temporary capital of the country. Its ten thousand residents were apparently not discouraged by the shambles that lay about them and immediately launched an energetic program for general reconstruction. Within the next four years the population doubled and the rush was on. Boom towns always attract a surrealistic swarm of immigrants from within their own country and abroad. Western Europe was politically restless, and the ranks of local merchants, financiers, and speculators were promptly invaded by their foreign counterparts. The Chamber of Commerce and the New York Insurance Company reopened their doors; the first independent bank was founded, and customs were drastically reorganized. A temporary crisis arose when Caribbean trade was cut off not only by Britain but by France and Spain as well. Undaunted, New Yorkers dispatched the Empress of China to Canton and welcomed her back a year later laden with tea and silk, signaling the start of the great China Trade.

The entire population of New York in 1784 could have gone to work daily in today's Pan-American Building. The city boasted four thousand houses set on about one square mile of land below Chambers Street, and business was conducted in a leisurely fashion at home or in a local tavern. But by 1800 the population had taken a leap to sixty thousand, and the city's boundaries expanded to Worth Street on Broadway, Harrison Street on the North River, and Rutgers Street on the East River. Artists and engravers of the period depicted New York as a sort of citified New England port town, serene and immaculate—a wonderland of green gardens, schooner masts, and graceful colonial architecture. But diarists saw it for what it was, a confusing paradox of luxury and squalor.

In writing his memoirs in the nineteenth century, one local resident recalled: "N. Y, was a dull and dirty town in 1789. It was a city without a bath, without a furnace, with bedrooms which in winter lay within the Arctic zone, with no ice during the torrid summers, without an omnibus, without a moustache, without a match, without a latch key." In May 1788, the Grand Jury had reported the streets to be dirty and many of them impassable. Pigs were the only scavengers. All wood delivered to stores or houses (there was no coal) was sawed and split on the street after delivery. Street lamps had been introduced in 1762; but they were few and poor, apt t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter I 1776-1800

- Chapter II 1800-1830

- Chapter III 1830-1860

- Chapter IV 1860-1914

- Chapter V 1914-1940

- Chapter VI 1940-1973

- Afterword The Coming of the American Food Revolution: 1973 to the Present

- Bibliography

- References

- Index