![]()

1

Just Starting Out

Background and Important Information

So you have decided you might want to be a performing singer/songwriter?

You may have been impressed by someone you heard on American Idol who said she wrote the song that she performed, or perhaps you have sung in church for years and been encouraged to go out and present your music to a wider audience, or maybe those gigs at the local tavern have been so much fun you want to turn it into a living and a lifestyle.

Whatever the case may be, it is a challenging yet potentially very rewarding life. It is fiercely competitive; if you are looking for great financial rewards, the chances of that are unpredictable. The great rewards of a career as a performing singer/songwriter lie in the experiences you will have and the friends you will make pursuing that goal in your life, as well as in the joy of creativity and seeing yourself grow as an artist.

However, there are ways you can increase your chances of being able to make a living as a songwriter/performer, if that is what you decide to do. There are also lessons to be learned from the artists and other persons interviewed in this book that should give you the confidence you need to move on to the next level, whatever that means for you.

Rather than trying to be a compendium of music theory, specific rhyming patterns, or formulas for writing the next hit song, this book is meant to be a portrait of the lifestyle of being a performing singer/songwriter, including commentary by artists who have and are still doing it in a successful manner, and some ideas on how you can get to that point. This is not a book that portrays the brief trajectory of pop music stars, but rather how some artists have succeeded in carving out a fulfilling career in an art form they believe in.

Some of these people have been successful in making their careers financially secure, and others have chosen to carve a less lucrative but just as rewarding path.

Becoming a songwriter, performer, or both is never a rational business decision. That is not to say it cannot be a profitable lifestyle, but the outcome is difficult to predict, no matter how talented you are.

There are many different ways to pursue this multifaceted, complicated business. In this chapter, I portray three different styles of being a singer/songwriter—but bear in mind there are many other ways to mix and match lifestyles and turn your avocation or passion for songs into either a career or an enjoyable sideline activity in your life.

Steve Gillette has some excellent words of advice in his book Song-writing and the Creative Process, advice that echoes my own feelings on this task that has the ability to touch so many lives:

There are many good reasons and creative activity that cannot be justified in terms of the top forty charts. If as songwriters we can connect with the immense energy and emotional truth in the heart of each of us waiting to be expressed and acknowledged, there is no limit to what a song can accomplish.

At the bottom of every bit of experience, advice, and instruction in this book, I hope that is what we are all striving for as songwriters.

Different Kinds of Composers

Full-Time New York/Nashville/Los Angeles Nonperforming Songwriters

This category is probably the smallest numerically. Some of the recognizable names in this division would be Harlan Howard, the well-known country songwriter, with dozens of #1 country hits; the late Cindy Walker, who wrote many of the songs that became hits for groups such as the Sons of the Pioneers and Gene Autry; and Diane Warren, who is probably the most successful nonperforming singer/songwriter today, with songs recorded by the Jefferson Airplane, Bon Jovi, and many other top groups.

This is the category that many music fans, housewives, and amateur singer/songwriters are convinced will bring them great riches. It is not a precise science by any means, and placing songs has more to do with music business connections and timing and less to do with the merit of the composition.

Placing a song with a music publisher in hopes of eventually having it land on a major artist’s album is indeed a long shot. There are many books that describe in depth how to go about this and give you the requirements that publishers request when you submit material, who is accepting songs, what kind of songs are being reviewed, and so forth. Some of these books are listed in the Biblography and Musician Resources section at the end of this book, and are well worth researching for specific information.

If you are an unpublished songwriter, the best single tool to help you is the annual guide Songwriter’s Market. It contains a large list of publishers, including some of their credits, addresses, phone numbers, e-mails, and so on. Every publisher in the book has agreed to accept unsolicited material or specifically state they will not accept such material. Any complaint against a publisher is investigated by the editors of the book; if they receive more than two complaints, they drop the publisher from next year’s book. We talk more extensively about this publication in later chapters, and complete information on it is available in the bibliography.

Here are a couple of useful hints that will help you to use the book; they mostly involve using common sense. If you see a rap music publisher in northern Idaho, you should be particularly careful in reviewing his credits. How much of a rap business exists there? Another no–no is to spot a publisher whose credits are all with the same record company, one that you have never heard of. Chances are that this publisher owns the record company, and these are not commercial records but glorified publishers’ demos.

It is a good idea to check to see that anyone mentioned in the listing still works at the company. You can search for the company on the Internet, send an e-mail, or make a phone call. Nothing marks you as an amateur faster than writing to someone who left a company months or years ago.

Use every resource and tool you can access, because there are hundreds of nonperforming songwriters in Nashville, Los Angeles, and New York, working subsistence jobs and ceaselessly barraging publishers and producers with material. These writers are very committed to succeeding and are cultivating music business connections and making contacts on a daily basis. Even so, only a tiny percentage of them will place songs with a major-label artist.

For the lucky few who do, the songwriting mechanical royalty (album sales), as of 2006, is 9.1 cents per unit, or 1.75 cents per minute, whichever amount is greater.

Airplay royalties are dependent upon rules that are constantly being renegotiated by the professional rights organizations (the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers [ASCAP], Broadcast Music Incorporated [BMI], the Society of European Songwriters, Artists, and Composers [SESAC], the Composers, Authors, and Publishers Association of Canada [CAPAC], and others). As a general rule, a crossover hit (a song that is on the top of the charts in more than one category of music) can net the songwriter/publisher $250,000 or more. Many of these kinds of songs become even more valuable over a long period of time as they are used for other purposes such as ad campaigns, movie scores, and other media.

These outlets can bring in an income of more than a million dollars for a single song. Future uses and airplay of a song can bring in considerable money for many years.

Songs are administered and placed by publishing companies, which generally take half of the proceeds for their trouble. Publishing contracts with writers are as varied in their terms as the number of songs that are written, but that 50 percent figure is a general rule of thumb, split between the publisher and composer.

Publishing companies and producers are the key to placing songs with major-label artists. Most of the recording artists who are not songwriters themselves rely very heavily on the judgment of their producers to choose songs. Again, more often than not, those songs recommended by their producers will be placed due to some personal connection with the writer that has been made.

Some publishers even have staff songwriters. These writers are given a monthly stipend, and for that sum they are expected to turn out a dozen or so acceptable songs per year for the publishing company that has them on staff. The stipend is deducted from any eventual royalty that the songs generate.

So you can see that if you are competing in the world of the non-performing songwriter, the competition will be substantial. This is not to say it cannot be done, but it is best to approach the challenge with a sense of realism and knowledge of the odds.

Most performing singer/songwriters, including myself, have hoped that at various times in our lives, particularly when raising a family, we could take a little time off of the road and let our songs do the work for us. “Mailbox money” is the term I first heard for those kinds of pleasant postal surprises.

Eliza Gilkyson says of that time in her life,

If I had achieved any success in pitching my songs, I might have just worked as a songwriter. I would have loved to have done that when I was raising my kids. I never had the contacts. I still don’t know how to get the songs to people. I still don’t have music business friends; I have lots of musician friends. I’m not really part of the music business scene; I never have been. The way songs get placed with other artists, from what I’ve seen over the years, comes from knowing and creating connections. I never wanted to live in Nashville. I am not good at targeting people as marks for me to work, to try to get my needs met.

I believe that is true for most songwriters; we are not necessarily the best people to pitch our own work, and we generally do not have the connections it takes to get a song placed.

Finding an established publisher who believes in your songs and is willing to take them on is the best way to place them with recording artists. You need a demo recording of your songs so that the publisher can evaluate your work.

If you are not an accomplished performer yourself, you are going to have to pay to have a demo that represents your songs in the best light possible. Expect to spend $1000 up to many thousands of dollars to have a good 4-song demo produced of your original material. You can, of course, have it done by friends for less—but bear in mind that you truly get what you pay for in recording. I will talk more about the recording process in a later chapter, but if you are serious about performing and getting your songs heard by other artists and publishers, you need to do a respectable recording of them as soon as you are able to do so.

Part-Time Composers with Day Jobs, Dreams, and a Few Gigs

If the first category in the chapter would be the smallest numerically, part-time composers and performers would definitely be the largest, and a group that nearly every singer/songwriter/performer has belonged to at some point in his or her life.

Let me stress that this book highlights a few techniques that songwriters such as Gordon Lightfoot, Eliza Gilkyson, Harry Manx, I, and others have used to make our way in the music business. However, there is not a right or wrong way, but rather a thousand different styles of doing this decidedly quirky vocation.

Most all of us have had to do other professions while moving in the direction of being able to pursue music full time. If we are lucky, we learn something about ourselves and become familiar with time-management tools that will serve us well in our career in music.

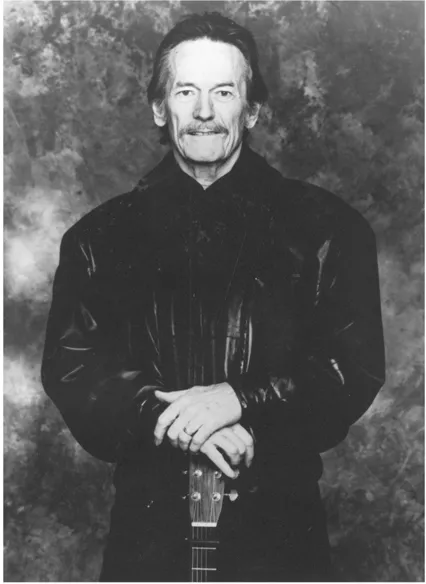

Gordon Lightfoot (see Figure 1.1) worked as a bank teller, a music copyist, a singer/dancer on a television variety show, and drove his dad’s laundry truck in the small Ontario town where he grew up. Eliza Gilkyson talks about some of her part-time jobs while she was writing songs, doing gigs, and raising a family:

Figure 1.1 Gordon Lightfoot. Courtesy of Gordon Lightfoot and Early Morning Productions.

I answered telephones for an answering service from 10 P.M. at night until 6 A.M. in the morning. I had to feed my kids dinner, put them to bed, then drive over and answer phones until dawn, then come home and send the kids off to school.

I was a gal Friday to my sister who was trying to help me figure out a way to support myself when I moved out to California. I was her assistant; she was a vice president at Warner Brothers in those days. I would work three or four hours a day a few days a week doing that.

I carried rugs in Boston, drove a taxicab in St. Louis, and did a little telemarketing in Omaha, Nebraska. We all do what we need to do to pay the bills, buy that better instrument, pay for that next recording, and hopefully move to the next level. In my experience in this business, few artists are given a free ride, and the ones who are don’t seem to have the fire in their belly that you need to take the risks and do the hard work that is needed to succeed.

The best kinds of day jobs when you are moving forward as a singer/songwriter seem to be the ones that are associated somehow with your craft of music. These are also jobs that can keep y...