1 What is the Internet and what is governance?

The chapter introduces the concept of the Internet as it has emerged, based on technology and how it might be defined. It then looks at what governance, as contrasted with government, would mean, again in current usage.

To be able to discuss Internet governance, we need to know what each term means. This is a significant question, because although the WSIS defined “Internet governance,” there is no agreed definition of what the Internet is, nor what governance implies. When the Internet is defined, the aspects that can be regulated can also be defined. When governance is defined, the limits of regulation will also be set out.

In communication theory, a communication consists of five parts: a sender, a message, a channel, a receiver and a feedback mechanism. At its simplest, for a traditional telephone conversation to take place, you (the sender) have a telephone into which you speak (the message) that carries your voice over either a fixed line or wireless (the channel) to the phone of another person (the receiver) who can reply (feedback). Of course, it is more complex than that. Your telephone has to be connected to a network that is run by a telephone company through either wires into your home or office or through a wireless transmission tower. That network has to be connected to the network that your receiver is on. Often the receiver’s network is supplied by a different company. It could even be a company in a different country, in which case there would have to be international standards to permit the call to go through. This would include such issues as the technical standards (which kinds of telephone numbers would be allowed) and financial arrangements (since the cost of the call is charged to the sender, how is the company providing services to the receiver of the call going to collect for its services). Internet mavens refer to this process as Plain Old Telephone Service (POTS).

Communication over the Internet is similar to POTS, but different in critical ways. It is a network of networks (which is where the term Internet comes from). There are senders (anyone using a computer to connect with the network), there are messages, in the form of e-mails or requests for information, there are channels including those made available by companies or institutions like universities—called Internet service providers (or ISPs) that connect the individual to the larger network of networks. There are channels, usually large fiber-optic cables called pipes, over which messages flow and there are recipients who are connected to the Internet though their own ISPs.

Here the similarities end. Unlike POTS, the Internet is borderless.

What is the Internet?

Although telephone switching systems have matured to the point that hundreds of millions of connections a day can be set up and maintained by the network, their essential characteristic remains a continuous fulltime pathway between two points at any one time.1

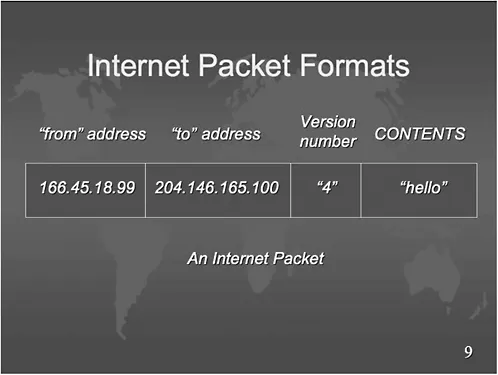

The Internet is based on a technology called packet switching. Packet switching represents a significantly different communications model. It is based on the ability to place content in digital form, which simply means that content can be coded into binary numbers (1 or 0), which is how computers store information. In packet switching, the content of communication, once put into digital form, is divided into small, well defined groups of coded data, each with an identifying numerical address. Anything that can be digitized can be sent as a packet. To the Internet, a packet is a packet is a packet, whether it carries numbers, words, digitized sounds or digitized pictures. It became possible, and the U.S. Defense Department’s Arpanet actualized the possibility (see Chapter 3), to send an unlimited number of packets over the same circuit with different addresses. Routers, rather than switches, became the key to delivering the packets to the intended destination. Figure 1.1 shows the packet format.2

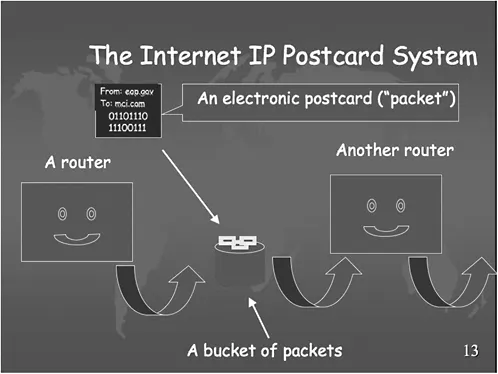

Controlled by software and microprocessors, the router inspects the address of a packet and sends it on its way on a full-time circuit to another router to an eventual end point. As the network technology evolved into the TCP/IP network that undergirds the Internet, the designers reserved 32 bits for the packet address (to be superseded by 128 bits in Internet Protocol version 6 [Ipv6]) which are represented in decimal notation in a format xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx, where each group of x’s can range from 0 to 255. Figure 1.2 shows how the packets are routed.

The Internet Protocol, an agreement on a standard for setting up packets, is one key part of the Internet. A second key part is the addressing system, the management of which was the first governance issue.

Figure 1.1 Internet packet formats.

Figure 1.2 The Internet IP Postcard system.

The innovation of a Domain Name System (DNS) in 1984, prior to the creation of the Web in 1988–89, provided synonyms for the somewhat inscrutable digit strings of the actual address. The actual addresses of the packets remained the digit strings but they were replaceable by more or less scrutable alphabetic equivalents stored on a DNS server file which permitted the lookup of the alphabetic name from a numerical address and vice versa. Thus was born the web site name, a new entity and a new property right in a new and legally ambiguous sphere.

By comparison, the telephone system addressing system started in the simplest possible fashion with Sally asking an operator to connect her to Harry. Under the direction of the Bell System-affiliated companies and by agreement with the non-Bell operating companies, the present U.S. ten-digit area code–exchange–line number system evolved over decades into a national standard. By contrast, the Internet addressing scheme was designed from its day of creation by engineers and scientists as a logical and comprehensive construct to meet their needs for low-cost data communication. The integrity of the scheme was guaranteed by its sponsorship by the U.S. Department of Defense and by later private sector successors.

The alphabetic names associated with numeric addresses were divided into domains, a limited typology of alpha addresses that enabled the routers to do their lookups efficiently. To find the numeric twin of the Internet address of “UN.ORG,” for instance, the router need not search through every entry in its address table, just the addresses ending in “.ORG.” These suffixes as the first level of searching and selecting are known as top level domains: the original set included .COM, .MIL, .ORG, .GOV and .NET, corresponding to net addresses for entities in commercial, military, non-profit, government and network administration endeavors.

Internet addresses are conceptually very different from telephone numbers. In the U.S.A., Canada and the Caribbean, most area codes (technically NPAs—National Planning Areas) denote a geographic place with boundaries identifiable with governmental jurisdictions: nations, states, cities. The exchange part of the phone number is traditionally associated with a specific place with a street address, the central office, from which the wires emerge to connect the telephone user over the “last mile” to the network. The place-centered nature of the phone system numbering plan is beginning to break down with the rise of wireless cellular systems, the widespread use of ghostly 800 and 888 numbers which may be answered here one minute and there the next. Nonetheless, jurisdiction can be established in all cases. Internationally, the country code, city code numbering system links phone number to place to the jurisdiction.

Internet addresses have no fixed location. They are purely conceptual. There is no central office. The routers which direct packets to the packet address at rates between 100,000 and 500,000 a second can know only the next logical point in a routing table and which outbound circuit is available to carry the packet. Packets are free to traverse the globe on countless circuits to geographically indeterminate end points. The technology provides assurance that the packets are reassembled in the right order and are very likely not corrupted by data errors.

A further distinguishing factor in net addresses is that neither the sender nor the receiver of a packet is a paying customer for the packet. Telephony requires two paying customers to complete a call, each of whom is paying for the privilege and each of whom has at a minimum a billing address and usually a street address in a city, a state/province and country. The Internet senders and receivers are inherently tied neither by the billing process, since they do not pay for the specific message nor the technology to place the message, since the packets can go by various channels.

The technical underpinnings of novel realities have led to major policy debates that are far from resolved. From inside the Internet, names for addresses are structured but purely arbitrary, the technology is indifferent to content, and the sender/receiver dyad is unlocatable in a conventional spatial sense.

The packets containing content are coded in the sender’s computer by e-mail programs, or by web-authoring programs. The computer is then connected to a local network by the Internet Service Provider through what are called servers—computers that have software to store and route data. In my case, when I am working from home, my computer is connected to Syracuse University’s computer facilities by my telephone company (although it could also be by my television cable company or even my electrical utility). The ISP’s routers send the packets toward the address that is their destination (and if the address is wrong, will send an error message). Usually this will be over the large fiber-optic cable networks called “pipes” that are owned by private companies. The packets will follow a path of least resistance and not all packets will follow the same path. This is one reason that the Internet is so efficient. Eventually (and this can be a very fast eventually since the packets go at approximately the speed of light), the packets arrive at the server managing the receiver’s address. In my case, e-mails sent to me at my Syracuse University address (syr.edu) will arrive at my mailbox, be joined together into a single message and I will be able to download them to my own computer and read the content.

How fast the content gets to me depends on a couple of factors. It depends on the speed of my computer, which has to decode the digital files into something I can read (through application software like Apple Mail, Microsoft Mail or the open source Mozilla Thunderbird for e-mail, or a web browser software like Mozilla Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer or Netscape). It also depends on the speed of my connection to my ISP. If I am at the University, I can connect via an Ethernet Local Area Network (LAN), if I am at home, it is via a telephone fiber-optic cable or a coaxial cable from the television cable company. The speed with which packets can be sent over these lines is called “bandwidth.”

Some content like e-mail requires very little bandwidth, because the number of packets is small. Other content, like digitalized movies, has massive numbers of packets and takes a long time to download. The content that a person can obtain depends in large measure on the bandwidth available and as the Internet has matured, this has increased.

So, what can we say that the Internet is? As can be seen, the simple question has a complicated answer. We can say simply that it is a communication channel or medium and as such a piece of the communication process. It is a network of networks, starting with the network of which a sender is a part, continuing to larger networks that link smaller ones, and finishing with the network of which the receiver is part. The networks connect because of agreed protocols. Most of these are technical pieces of engineering software that are agreed by technicians. As institutions, the Internet is made up of individuals who get services from institutions (companies, universities, government offices) who get services from other institutions who may invest in infrastructure or technological development.

In seeking to provide a useful definition, Milton Mueller, Hans Klein and I proposed a concise definition of the Internet:3

The Internet is the global data communication capability realized by the interconnection of public and private telecommunication networks using Internet Protocol (IP), Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), and the other protocols required to implement IP internetworking on a global scale, such as DNS and packet routing protocols.

For most things, the Internet operates automatically. Once you have written an e-mail and given the address of the recipient, the rest is taken care of by the protocols and the machines they run on.

So why do we worry about governance of this system? If we didn’t have to worry about either the content of messages being sent over the system, or the cost of running or joining the Internet, only a very simple form of management would be needed. There would only have to be a mechanism to agree on the protocols that make the networks link to each other and there would have to be some means of maintaining order in the addressing system. In fact, as we will see in more detail in Chapter 3, this was how the Internet was originally run. A group of engineers and scientists would get together periodically through an ad hoc body that called itself the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) to agree on the content of protocols. One individual, Professor Jon Postel of the computer center at the University of Southern California, ran a directory that contained all of the addresses being used.

This ideal state only lasted a very short time, because a large number of policy issues intruded on the Internet, many of which did not directly relate to the engineering architecture of the system, but all of which were either causes or consequences of issues with the technology.

One way to look at policy is to use the component parts of communication: (a) a sender, (b) a message, (c) a channel or medium, (d) a receiver, and (e) feedback. Each component has its own policy issues and stakeholders. Table 1.1 shows some of these issues, both at the national and international levels and the stakeholders concerned with them.

It is no coincidence that the first two universal international organizations were concerned with communications: the Universal Postal Union and what was then named the International Telegraph Union (see Chapter 2 for details). Without some regulatory mechanism, communication flows over national borders could not be assured. Both institutions have endured (with the IT...