C

CADET NURSE CORPS

If the name of this program sometimes was confused, its objective was not: often called the “Student Nurse Corps” or variations of those words, it clearly aimed to recruit more nurses—and in the context of the time, that meant young women. Only women belonged to the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) or the Navy Nurse Corps (NNC), both of which had been established early in the twentieth century. Unlike male military members who were trained after their enlistment, women who joined the ANC or NNC had to first earn their nursing degree at their own expense.

In December, 1941, ANC members were caught in the Japanese invasion of the Philippines; these nurses worked themselves to literal exhaustion in Bataan and Corregidor, and some ended up as prisoners of war. The tragedy made it clear that the nation was desperately short of skilled nurses, and one of their responses was the Cadet Nurse Corps. It existed under the aegis of the U.S. Public Health Service, which belonged bureaucratically to the Surgeon General. Its leadership also worked closely with the Red Cross, the American Nurse Association, and high school educators to attract more young women into the profession.

The need was great. Several months before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Public Health Service reported some ten thousand vacancies for hospital nurses—not including the many non-hospital positions that nurses fill. Health officials wanted fifty-five thousand new nursing students in 1942, and in 1943, when the Cadet Nurse Corps finally began, the recruitment quota was raised to sixty-five thousand.

There were good reasons why the nation faced a nursing shortage: in addition to the millions of casualties that the war would bring, many things about the profession—and especially public perception of it—needed reform. In the decade prior to the war, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, relatively few women could afford to go to nursing school, and the nation had done virtually nothing to correct that.

Worse, many upper-class people still regarded public health in general as something that applied only to the poor: wealthy families did not send their loved ones to hospitals; instead, the doctor came to the home, where private nurses carried out his orders—as well as performing the menial tasks that nursing involves. Many opinion makers thus regarded nurses as only slightly more qualified than the average household servant.

Nursing schools did an unfortunate amount to reinforce this view. Schools almost always operated in conjunction with a hospital, where students lived and worked under strict supervision. Hospitals routinely exploited these students, requiring them to spend a great deal of time changing bedpans, serving meals, and doing other menial chores on the wards instead of being in a classroom to study anatomy, physiology, etc. Their free time was limited, and discipline often was harsh.

As the economy improved with the beginning of the war, young women began to have alternatives to this self-sacrificing life. They saw that they could earn more in a defense plant doing jobs formerly done by men, and their non-working time was free of restrictions. Societal gender rules were changing and young women no longer had to pay tuition to a nursing school for the “privilege” of providing free labor to a hospital.

The Public Health Service and other interested parties thus had a greater task than merely advertising for women to go into nursing: they also had to change public attitudes and reform the habits of hospitals and nursing schools. Young women only could be attracted to nursing schools if the profession was seen as truly modern science, and the creation of that image called for a new organization. Thus the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps was born.

The war’s greatest occupational shortage was nurses, who were assumed to be young women. Courtesy of Library of Congress

Like many other ideas related to nursing, it was primarily the brainchild of Representative Frances Bolton of Ohio. The need for nurses was so clear and Bolton’s plans for addressing the need were so well thought out that not a single member of Congress voted against the Bolton Act, which passed both houses and was signed by the president in May of 1943.

The Public Health Service was ready with advertising that—like almost everything else during World War II—emphasized an official uniform. That of the Cadet Nurse Corps looked much traditional nurses: it featured a white skirt and cap at a time in which, except for military parade occasions, the Army Nurse Corps had switched from white to dark fabric and from skirts to pants. The student uniform, however, was designed not so much for working practicality as to reassure parents and to inspire historic patriotism.

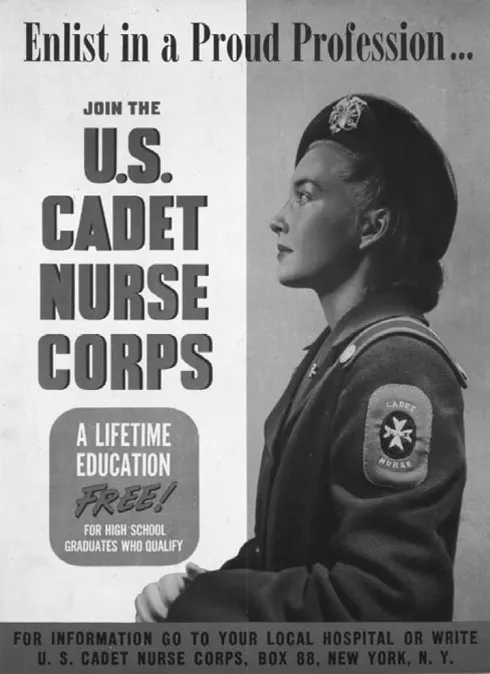

Recruiting posters depicted young women in these uniforms with text messages such “A Lifetime Education Free for High School Graduates who Qualify—U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps.” Another, which was issued by the Office of War Information in 1944, not only reinforced the self-interested message above, but went further to imply that a young woman must hurry or lose her chance. It read, “Join the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps—Only 5, 416 Opportunities to Enlist this Month—A Lifetime Education in a Proud Profession.” Recruitment nonetheless continued as the war wound down in 1945: then the Veterans Administration issued posters depicting nurses caring for young men in VA hospitals, some of whom would have to live permanently with their injuries.

Washington officials in charge of the corps also coordinated closely with state departments of education. They used the Department of Education’s periodical, Education for Victory, to make school administrators, guidance counselors, and teachers aware of the issues. They sent speakers to talk to teenage girls about nursing school, organized events to encourage enrollment, and even reached out to minorities, including Japanese Americans. Ultimately, some 120,000 women benefited from the Bolton Act, many of whom also donned the uniform of the Cadet Nurse Corps. The program indeed was historic: never before had the federal government invested so much to encourage education expressly designed for female students.

See also: African-American women; American Nurses’ Association; Army Nurse Corps; Bataan; Bolton Bill; Corregidor; Japanese-American women; Navy Nurse Corps; nurses; Red Cross; uniforms

References and further reading

Aynes, Edith A. From Nightingale to Eagle: An Army Nurse’s History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1973.

“Cooperate in Meeting Nurse Shortage,” Education for Victory, May 15, l943.

Haupt, Alma C. “Bottlenecks in Our War Nursing Program,” American Journal of Public Health, June 1943.

“Nursing is War Work With a Future,” Education for Victory, April 15, 1943.

“Nursesto-Be and the Victory Corps,” Education for Victory, January 15, 1943.

Robinson, Thelma M. Nisei Cadet Nurse of World War II. Boulder, CO: Black Swan Mill Press, 2005.

Robinson, Thelma M., and Paulie M. Perry. Cadet Nurse Stories: The Call for and Response of Women during World War II. Indianapolis, IN: Nursing Center Press, 2001.

Smith, Edith H. “Educators Look at Nursing,” American Journal of Nursing, June, 1943.

Perry, Lucille “The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps,” American Journal of Nursing, December, 1945.

“Toward Solving the Nursing Problem,” Education for Victory, April 1, 1943.

Zeinert, Karen. Those Incredible Women of World War II. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press, 1994.

CAMP FOLLOWERS

Since the nation began with the American Revolution, this term has been used to denote women who followed men to military camps. Often the intent is tainted with slander, implying that they are prostitutes or at least women of questionable morals. That this should not necessarily be the case is clear when we recall that Martha Washington and other leading ladies of early American history accompanied their men to camp, especially in the winter. Like other women, Washington returned to Mount Vernon to supervise the busy agricultural summer, but she shared her husband’s dark days at Valley Forge.

Despite the fact that the nation’s founders clearly appreciated female presence, military science in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries accepted as dogma that camp followers were a damaging influence. In World War II, as in earlier wars, most officials resisted allowing civilian women anywhere near military posts, whatever their relationship to a soldier might be. Leaders feared, often with justification, that especially drafted men would prioritize their wives or sweethearts ahead of military duty.

Other authority figures reinforced the military’s view. Physician Leslie B. Hohman, for instance, titled one of his monthly columns for Ladies Home Journal, “Don’t Follow Your Husband to Camp.” Most male sociologists, ministers, and so forth also urged women to stay home, rarely considering the possibility that having a wife nearby might stabilize a young man, make him work harder, and keep him away from negative influences.

Because almost all local leaders echoed the military opinion, many residents near military installations treated women who followed their husbands to camp with open hostility. Many such locales already were overcrowded, as, for instance, the Navy placed new training bases on coasts jammed with bustling shipyards. Airfields also were likely to be on the coasts or in the South, where warm weather allowed year-round flying.

Coastal cities were accustomed to newcomers and less hostile, but despite legendary hospitality, many residents of small Southern towns could be decidedly rude to the young Yankee women who suddenly appeared by the hundreds in insular Alabama or South Carolina. This was especially so when local military commanders all but officially declared such women to be a public nuisance.

Nonetheless, hundreds of thousands of women defiantly endured difficult travel and uncomfortable lifestyles so that they could be with their men during what might turn out to be the last months of his life. Some local women, especially those with children in the service, quietly differed from the official advice and empathized with camp followers. Barbara Klaw, for example, followed her husband from their New York City home to Neosha, Missouri: she said that although the male USO head there declared that “Army wives frankly were a bother,” the YWCA workers “strongly defended, brooded over and mothered” the young women. “All day long,” Klaw continued:

girls climbed the steep hill to Neosha’s magnificent U.S.O. club ... We didn’t jam the rooms as soldiers did at night, but we used every facility constantly. By the time my daily shift at the reception desk started at five o’clock, the little meter that recorded the number of people entering the building usually read about 200, few of whom by that time of day had been soldiers.

These women used the ironing boards, sewing machines, and other things not available to them in the rented rooms of Neosha homes that they were lucky to find. In similar towns throughout the nation, young women begged to rent an attic space or a portion of a garage or basement so that they could be near their man. Such rentals rarely came with private bathrooms, and Klaw said that camp followers also depended on the USO for that. During “two hours every morning,” men were banned from the building’s basement showers so that “girls who lived in unequipped homes” could use the facilities.

It is understandable that homes in Missouri’s Ozarks did not yet have modern showers, but many landladies there and elsewhere failed to be hospitable in other ways. There were, of course, exceptions, but most local residents seemed to think that the military’s unwelcome attitude toward camp followers justified hostility and exploitation. They charged unconscionable rent for barely habitable housing, refused to allow cooking or even coffeepots in rooms, forbade the use of the family telephone, and even doled out toilet paper by the sheet.

Nor could young couples expect any real privacy in these rooms during the few hours that they could be together. Soldiers had to be in their barracks at lights-out, and the only time that husbands and wives could spend together was in the evening—when the men often had to study for the next day’s classes. Whether or not a soldier got a weekend pass depended on the whim of his sergeant, and even if he did, gas rationing meant that couples rarely could go anywhere or do anything beyond the limited choice of a small town’s jammed movie theater or overpriced cafe.

Unmarried soldiers also found such stations difficult, as one described these “Armytowns” to New Republic:

There’s only two kinds of girls in Armytown ... soldiers’wives or anybody’s gals . . Every time I come into town I start to ask myself whatinhell I did it for ... Some fellas wandering up and down; a few with their gals—the lucky ones—but mostly they’ve got the paintbrush ready only there’s nothing to paint.

Nothing, too, was the situation with employment, as very few employers were willing to hire a woman they knew soon would move. Although many camp followers had work experience and although there was a genuine national labor shortage, it was extremely difficult for these women to work, especially given the difficulties of wartime transportation. The most likely employment in such places were service jobs—but they often came with a reputation too tainted for the moral code of the place and time: writer Gretta Palmer, for instance, reported that “Travelers Aid was unable to find a room in any respectable home of a large town for a soldier’s wife with a waitress job.”

Unless a couple had parents capable of subsidizing this point in their young lives, camp followers faced a penny-pinching existence on the monthly $50 that most soldiers earned. Ladies Home Journal wrote of the thirty thousand women who accompanied men to San Antonio airfields in 1943. “The days are very empty,” the magazine said of a representative woman, with her unwanted leisure enlivened only by “a radio in her room” and occasional movies. The bus ride to her husband’s base was too complex and expensive for weekday evenings, and she lived only for the weekends when he could visit.

Another of these San Antonio women, “June,” was fortunate enough to find a job, but she faced a complicated fut...