- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

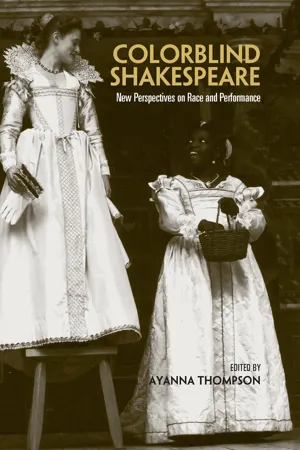

The systematic practice of non-traditional or "colorblind" casting began with Joseph Papp's New York Shakespeare Festival in the 1950s. Although colorblind casting has been practiced for half a century now, it still inspires vehement controversy and debate.

This collection of fourteen original essays explores both the production history of colorblind casting in cultural terms and the theoretical implications of this practice for reading Shakespeare in a contemporary context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Colorblind Shakespeare by Ayanna Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism of Shakespeare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Practicing a Theory/Theorizing

a Practice: An Introduction to

Shakespearean Colorblind Casting

The systematic practice of nontraditional or colorblind casting began with Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival in the 1950s. Although colorblind casting has been practiced for half a century now, it still inspires vehement controversy and debate. The black playwright August Wilson famously decried: “Colorblind casting is an aberrant idea that has never had any validity other than as a tool of the Cultural Imperialists…. It is inconceivable to them that life could be lived and even enriched without knowing Shakespeare” (Wilson, 29). Wilson’s focus on Shakespeare within his argument against colorblind casting relies on several important but unmentioned suppositions about the relationship between England’s most famous playwright and this twentieth-century casting practice. First, the practice of colorblind casting is inextricably enmeshed in the contemporary history of Shakespearean production. Second, the immense and enduring weight of Shakespeare’s cultural legacy has helped to create the perceived need for colorblind casting. And finally, the popular notion that Shakespeare’s plays are “universal” lends itself to the theory that casting agents, directors, actors, and audiences can be “blind” to race, color, and/or ethnicity. These fascinating suppositions, which have been critically neglected, are the focus of Colorblind Shakespeare. This collection explores both the production history of colorblind casting in cultural terms and the theoretical implications of this practice for performing Shakespeare in a contemporary context.

Back in the Day: The History of Colorblind Casting

When the African Theatre in New York, a company comprised of and for ex-slaves and the sons of ex-slaves, put on a production of Richard III in 1821, white critics ridiculed the black actors: “People of colour generally are very imitative, quick in their conceptions and rapid in execution … [and are better suited for] the lighter pursuits requiring no intensity of thought or depth of reflection” (Noah 1821a). Theatre, and in particular the performance of Shakespeare’s language, was deemed too difficult for these uneducated ex-slaves. Transposing his rendition of the black Richard’s first lines, one critic wrote: “Now is de vinter of our discontent made glorus summer by de son of New-York.” The critic then derisively noted, “It was evident that the actor had not followed strictly the text of the author” (Noah 1821b). Another white visitor to the African Theatre intoned that it was “too much for frail flesh and blood to see an absolute negro strut in with much dignity, bellowing forth.” He added that seeing blacks perform in Richard III forced one “to hear the King’s English murdered” (Nielson, 20). Close to 150 years later, in 1963, the same type of criticism could be heard about a multiracial casting of Antony and Cleopatra: “Negro actors often lack even the rudiments of Standard American speech…. It is not only aurally that Negro actors present a problem; they do not look right in parts that historically demand white performers” (John Simon in the Hudson Review, quoted in Epstein, 291). In a fascinating displacement, these critics voiced their objection to the sight of black actors performing Shakespeare through a critique of the actors’ inappropriate mastery of Shakespeare’s language. These passages exemplify how Shakespeare’s language began to represent a powerful cultural capital that these critics felt should be withheld from people of color.

Although Shakespeare is often described as having created “universal” plays with “timeless” themes, the universality and timelessness of the Bard’s works are often tested when actors of color are involved. What is revealed in the quotations above is the fact that Shakespeare has historically been held as a litmus test for civility and culture.1 For example, there are stories of black Americans being denied the right to vote because they could not recite specific lines from Shakespeare. Of course, their poor and illiterate white American counterparts did not have to endure the same literacy tests at the voting booth. The historian Shane White, writing about the early nineteenth century in the United States, argues that “the body of [Shakespeare’s] work became an important part of the linguistic barrier that whites used to hem in the recently freed blacks in northern cities [in America] and thus to continue their subjugation. The great dramatist had rapidly become, for blacks, a suffocating presence” (White, 69). Shakespeare, far from being described as the father of “the human,” as he has been called by one recent critic, was instead the test to limit the freedoms of certain humans.2 The practice of colorblind and nontraditional casting sought to address and redress the appropriation of Shakespeare’s works as a “suffocating presence” for people of color.

Although there were all black troupes (like the African Theatre in New York) and black actors (like James Hewlett and Ira Aldridge) who performed in various Shakespearean productions and Shakespearean monologue performances in the nineteenth century, these performances were never conceived of or advertised as colorblind or nontraditional. Instead, these actors primarily performed Shakespeare’s “black” roles: Aaron the Moor in Titus Andronicus, the Prince of Morocco in The Merchant of Venice, and Othello. If they did take on the popular Shakespearean roles of the nineteenth century — Richard III, Shylock, and King Lear — then they performed in “whiteface.” Far from performing Shakespearean characters as if they represented universal types in which race had no bearing, these nineteenth-century black actors were extremely attentive to their own color.3 For example, Ira Aldridge, the famous black American actor who toured England and Europe throughout the mid-nineteenth century, first made a name for himself in 1825 playing the African prince Oroonoko in The Revolt of Surinam, or a Slave’s Revenge. He eventually became famous for his portrayals of Othello and Aaron the Moor. Although the portraits and daguerreotypes of him performing as Othello and Aaron are widely reprinted and therefore more familiar to twenty-first-century scholars and performers, his fame in the nineteenth century came as much from his whitefaced roles, such as Shylock, Macbeth, and Lear, as from his “black” ones.

Figure 1.1 Ira Aldridge as King Lear. Photo owned by Bakhrushin State Central Theatrical Museum, Moscow.

It was not until the 1940s that black actors began to appear in nonblack roles without the aid of whiteface. For example, the black actor Canada Lee performed as Caliban in Margaret Webster’s 1945 production of The Tempest in New York. Lee is thought to be the first black actor to portray Caliban, and it is believed that his portrayal represents one of the first nonblack Shakespearean roles assigned to a black actor in a mixed cast.4 But not even Lee can be considered a visionary in the forefront of colorblind casting, since one year later, in 1946, he performed as Bosola in The Duchess of Malfi in whiteface. Clearly, then, historically it has been difficult to balance the supposed universality of Shakespeare’s plays and characters with notions of the actual significance of race and color. Universality was not understood as being raceless in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

It was not until the 1940s, as Actor’s Equity and the Dramatist’s Guild were fighting against the segregation of the theatres, that colorblind casting came to the forefront. The desegregation of the theatres forced a discussion about the significance of race in performance. Joseph Papp, who eventually pioneered the systematic practice of colorblind casting in his New York Shakespeare Festival, spoke frankly about the problems of segregated theatres of the 1940s. As a member of the Actor’s Lab in Los Angeles in the 1940s, Papp wrote a letter to the Los Angeles Daily News protesting the columnist Hedda Hopper’s invective against the Lab’s racially mixed social events: “In the best tradition of theatre and democracy, there was no discrimination against fellow human beings. We, as a theatre, are part of the tremendous struggles being waged by Equity and the Dramatist’s Guild against the segregation of the theatres” (quoted in Epstein, 69). A truly integrated theatre that practiced colorblind casting, Papp argued, would necessarily challenge the overdetermined nature of color and thus deconstruct the need for whitefaced performances. Papp envisioned a theatre in which race would have no reliable signification in performance.

Unlike Papp, however, the leaders of the Lab perceived that there were significant impediments facing the desegregation of the theatres. They couched their argument in terms of the quality of the black actors available, attempting to disavow the notion that the problems might stem from the actual integration of black and white actors. In 1945 members of the Actor’s Lab met with Paul Robeson, the most famous black actor of the time, to discuss “the problems of the Negro actor.” The problems were clearly pinpointed: (1) there were not enough classically trained actors of color, so the language of the classics posed a challenge; (2) there was not a sufficient audience base among populations of color, so aspiring actors of color were not exposed to enough classical theatre; and (3) the trend of presenting classic plays by authors like Shakespeare “historically” often meant that actors of color were limited to the few “black” roles written.

It is interesting to note how many of these perceived problems were about classical theatre pieces, despite the fact that the Lab did not focus on the classics. Just as had happened in the nineteenth century, the idea of Shakespeare and classical theatre was appropriated as a litmus test for authority, civility, and culture that actors of color were set up to fail. The myth of Shakespeare’s universality was sacrificed for the myth of Shakespeare’s historicity when the Lab frequently rejected proposals for colorblind casting as “historically inappropriate.” Papp recalled, “They talked about a problem with minorities, a lot of these people. But they did nothing” (quoted in Epstein, 69). Papp vowed to do something instead of just talking about it. The use of colorblind casting in Shakespearean productions became one of his signature practices, and his insistence on employing the practice for Shakespeare’s plays marks an important counter-appropriation of the Bard’s cultural capital.

Proving the old maxim that life imitates art, Papp’s first introduction to Shakespeare in performance came from the only black teacher in his Brooklyn high school. Eulalie Spence, Papp’s speech coach and mentor, arranged for him to see two productions of Hamlet that were playing on Broadway in 1936. Seeing both John Gielgud and Leslie Howard in the competing title roles, Papp decided at that young age that he did not like a declamatory style of acting. He preferred a more naturalistic Shakespeare, and when he opened his New York Shakespeare Festival twenty years later in 1955, colorblind casting was part of his naturalistic approach. The language and the actors would sound and look more like the world around them. Papp said, “If you try to reproduce a play the way it was done originally … it becomes a museum piece. You have to draw from what exists. What exists in New York, and all throughout the world are different colored people” (quoted in Gaffney, 39–40). Turning the racist focus on Shakespeare’s language on its head, Papp appropriated the perceived aural problems: he promoted the idea that Shakespeare’s language became natural and living in the mouths of people of color. From the 1950s to the 1970s, famous actors such as Gloria Foster, Ruby Dee, James Earl Jones, Roscoe Lee Browne, Raul Julia, Morgan Freeman, Denzel Washington, and Michelle Shay actually received their start in Papp’s colorblind castings of Shakespeare. One must wonder how many of these actors would be living in obscurity without having benefited from the cultural capital of William Shakespeare in Papp’s wildly popular and populist colorblind productions.

Talking the Talk: Defining the Practice

Ellen Holly, a black actress who joined Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival in 1957, gives voice to the conundrum black actors faced in the mid-twentieth century. She had trouble finding work because she was considered both “inappropriate for white roles because [she] was black and inappropriate for black roles because [she] was light.” Holly states:

Given this mind-bending scenario in which your own personhood has to be constantly obliterated for you to be deemed acceptable, the Festival fell into my lap as something of a miracle — not only the sole venue where I could work with some kind of consistency, but the sole venue in which it was okay to work with my own face. (quoted in Epstein, 169)

Colorblind casting sought to create an environment in which actors were judged not on their “personhood” or their “own face” but on their talent. Colorblind casting, therefore, was based on a meritocratic model in which talent trumped all other aspects of an actor’s “personhood.” This was the original idea behind colorblind casting, but the practice has created complex theoretical disputes. In some ways, it is difficult to write about colorblind casting because its theoretical underpinnings are so unstable that they make the practice itself not one practice but a set of practices that not only are in competition with one another but also are deconstructing one another. Before delving into a more closely focused theoretical analysis of colorblind casting, I would like to describe the three main ways in which the practice of colorblind casting manifests itself. The disparate nature of these practices speaks volumes about the challenges facing this particular formation of nontraditional casting.

The initial idea behind colorblind casting was that neither the race nor the ethnicity of an actor should prevent her or him from playing a role as long as she or he was the best actor available. In other words, the best actor, regardless of race, should be cast for the best part. In this approach the audience is expected to make a distinction between the actor’s appearance and the character’s position, just as the audience would differentiate between a mask and a face, or even more fundamentally between the sign and the signified. Denzel Washington’s portrayal of Don Pedro in Kenneth Branagh’s film version of Much Ado About Nothing (1993) is a good example of this approach to colorblind casting. The audience is expected to ignore or forget Washington’s race and only see Don Pedro as the “Prince of Aragon.” His bastard brother, Don John, is played by Keanu Reeves in the film, and once again the audience is expected to differentiate between the fact that the actors, Washington and Reeves, are of different races and the fact that the characters, Pedro and John, are not supposed to be.5 In this version of colorblind casting, the onus of being “blind” to race is completely on the audience. In other words, the casting agents, directors, and producers who employ this approach assume that blindness to an actor’s race is not only desirable but also possible.

Almost from the beginning, however, another very different practice for colorblind casting emerged. Some actors and directors began to complain that this “blind” approach was not always appropriate, especially for roles in which the race of the character was central to the plot. Thus, a practice emerged in which the best actor was hired for the best role, except when the race of the character was identified and significant within the corpus of the text. Under this practice, for instance, it became unacceptable for white actors to play Othello in blackface, even if a whi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- 1 Practicing a Theory/Theorizing a Practice: An Introduction to Shakespearean Colorblind Casting

- Part I: The Semiotics of (Not) Viewing Race

- Part II: Practicing Colorblindness: The Players Speak

- Part III: Future Possibilities/Future Directions

- Notes on Contributors

- Index