![]()

1

Introduction

Overview and Aims

Missing data are a nearly ubiquitous aspect of social science research. Data can be missing for a wide variety of reasons, some of which are at least partially controllable by the researcher and others that are not. Likewise, the ways in which missing data occur can vary in their implications for reaching valid inferences. This book is devoted to helping researchers consider the role of missing data in their research and to plan appropriately for the implications of missing data. Recent years have seen an extremely rapid rise in the availability of methods for dealing with missing data that are becoming increasingly accessible to non-methodologists. As a result, their application and acceptance by the research community has expanded exponentially.

It was not so very long ago that even highly sophisticated researchers would, at best, acknowledge the extent of missing data and then proceed to present analyses based only on the subset of participants who provided complete data for the variables of interest. This “list-wise deletion” treatment of missing values remains the default option in nearly every statistical package available to social scientists.

Researchers who attempted to address issues of missing data in more sophisticated ways risked opening themselves to harsh criticism from reviewers and journal editors, often being accused of making up data or being treated as though their methods were nothing more than statistical sleight of hand. In reality, it usually requires stronger assumptions to ignore missing data than to address them. For example, the assumptions required to reach valid conclusions based on list-wise deletion actually require a much greater leap of faith than the use of more sophisticated approaches.

Fortunately, the times have changed quickly as statistical software developers have gone to greater lengths to incorporate appropriate techniques in their software. At the same time, many social scientists with sophisticated methodological skills have helped to facilitate a better conceptual understanding of missing data issues among non-methodologists (e.g., Acock, 2005; Allison, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002). There is now the general expectation within the scientific community that researchers will provide more sophisticated treatment of missing data. However, the implications of missing data for social science research have not received widespread treatment to date, nor have they made their way into the planning of sound research, being something to anticipate and perhaps even incorporate deliberately.

Statistical power is the probability that one will find an effect of a given magnitude if in fact one actually exists. Although statistical power has a long history in the social sciences (e.g., Cohen, 1969; Neyman & Pearson, 1928a, 1928b), many studies remain underpowered to this day (Maxwell, 2004; Maxwell, Kelly, & Rausch, 2008). Given that the success of publishing one’s results and obtaining funding typically rest upon reliably identifying statistically significant associations (although there is a growing movement away from null hypothesis significance testing; see Harlow, Mulaik, & Steiger, 1997), there is considerable importance to learning how to design and conduct appropriate power analyses, in order to increase the chances that one’s research will be informative and in order to work toward building a cumulative body of knowledge (Lipsey, 1990). In addition to determining whether means differ, assumptions (e.g., normality, homoscedasticity, etc.) are met, or a more parsimonious model performs as well as one that is more complex, there is greater recognition today that statistically significant results are not always meaningful, which places increased emphasis on the choice of alternative hypotheses.

We have several aims in this volume. First, we hope to provide social scientists with the skills to conduct a power analysis that can incorporate the effects of missing data as they are expected to occur. A second aim is to help researchers move missing data considerations forward in their research process. At present, most researchers do not truly begin to consider the influence of missing data until the analysis stage (e.g., Molenberghs & Kenward, 2007). This volume can help researchers to carry the role of missing data forward to the planning stage, before any data are even collected or a grant proposal is even submitted.

Power analyses that consider missing data can provide more accurate estimates of the likelihood of success in a study. Several of the considerations we address in this book also have implications for ways to reduce the potential effects of missing data on loss of statistical power, many under the researcher’s control. Finally, we hope that this volume will provide an initial framework in which issues of missing data and their associations with statistical power can become better explored, understood, and even exploited.

As resources to conduct research become more difficult to obtain, the importance of statistical power grows as well, along with demands on researchers to plan studies as efficiently as possible. At the same time, the increase in application of complex multivariate statistics and latent variable models afforded by greater computing power also places heavier demands on data and samples. In the context of structural equation modeling, there is generally also a greater theoretical burden on researchers prior to the conduct of their analyses. It is important for researchers to know quite a bit in advance about their constructs, measures, and models. The process of hypothesis testing has become multivariate and, particularly in nonexperimental contexts, subsequent stages of analysis are often predicated on the outcomes of previous stages. Fortunately, it is precisely these situations that lend themselves most directly to power analysis in the context of structural equation modeling.

History is also on our side. Designs that incorporate missing data (so-called incomplete designs) have been a part of the social sciences for a very long time, although we do not often think of them in this way. Some of the classic examples include the Solomon four-group design for evaluating testing by treatment interactions (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Solomon, 1949) and the Latin squares design. More recent examples include cohort-sequential, cross-sequential, and accelerated longitudinal designs (cf. Bell, 1953; McArdle & Hamagami, 1991; Raudenbush & Chan, 1992; Schaie, 1965). However, with the exception of the latter example, these designs have not typically been analyzed as missing data designs but rather analyzed piecewise according to complete data principles.

In Solomon’s four-group design (Table 1.1), for example, researchers are typically directed to test the pretest by intervention interaction using (only) posttest scores. Finding this to be nonsignificant, they are then advised either to pool across pretest and non-pretest conditions for a more powerful posttest comparison or to consider the analysis of gain scores (posttest values controlling for pretest values). Each approach discards potentially important information. In the former, pretest scores are discarded; in the latter, data from groups without pretest scores are discarded. It is very interesting to note that Solomon himself initially recommended replacing the two missing pretest scores with the average scores obtained from O1 and O3 in Table 1.1, leading Campbell and Stanley (1963) to indicate that “Solomon’s suggestions concerning these are judged unacceptable” (p. 25) and to suggest that pretest scores essentially be discarded from analysis. If you think about it, the random assignment to groups in this design suggests that the mean of O1 and O3 is likely to be the best estimate, on average, of the pretest means for the groups for which pretest scores were deliberately unobserved. How modern approaches differ from Solomon’s suggestion is that they capture not just these point estimates, but they also factor in an appropriate degree of uncertainty regarding the unobserved pretest scores. In this design, randomization allows the researcher to make certain assumptions about the data that are deliberately not observed.

TABLE 1.1

Solomon’s Four-Group Design

|

| | Pretest | Intervention | Posttest |

|

R | O1 | X | O2 |

R | O3 | | O4 |

R | ? | X | O5 |

R | ? | | O6 |

|

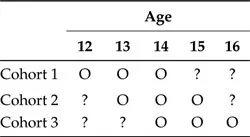

TABLE 1.2

Accelerated Longitudinal Design

In contrast, compare this approach with the accelerated longitudinal design, illustrated in Table 1.2. Here, one can deliberately sample three (or more) different cohorts on three (or more) different occasions and subsequently reconstruct a trajectory of development over a substantially longer period of development by simultaneously analyzing data from these incomplete trajectories. In this minimal example, just 2 years (with three waves of data collection) of longitudinal research yields information about 4 years of development with, of course, longer periods possible through the addition of more waves and cohorts. Different assumptions, such as the absence of cohort differences, are required in order for this design to be valid. However, careful design can also allow for appropriate evaluation of these assumptions and remediation in cases where they are not met. In fact, testing of some hypotheses would not even be possible using a complete data design, as is the case with Solomon’s four-group design.

On the other hand, an incomplete design means that it may not be possible to estimate all parameters of a model. Because it is never observed, the correlation between variables at ages 12 and 16 cannot be estimated in the example above. Often, however, this has little bearing on the questions we wish to address, or else we can design the study in a way that allows us to capture the desired information.

This book has been designed with several goals in mind. First and fore-most, we hope that it will help researchers and students from a variety of disciplines, including psychology, sociology, education, communication, management, nursing, and social work, to plan better, more informative studies by considering the effects that missing data are likely to have on their abi...