eBook - ePub

Birth By Design

Pregnancy, Maternity Care and Midwifery in North America and Europe

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Birth By Design

Pregnancy, Maternity Care and Midwifery in North America and Europe

About this book

This collection of essays contains leading research in maternity care from Europe, the United States and Canada to discuss systems of care for pregnancy and childbirth. Birth By Design focuses on the practical side of 'good' social science research. This is a ground-breaking work that looks not only at maternity, but also the act of childbirth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Birth By Design by Raymond De Vries, Cecilia Benoit, Edwin van Teijlingen, Sirpa Wrede, Raymond De Vries,Cecilia Benoit,Edwin van Teijlingen,Sirpa Wrede in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I:

The Politics of Maternity Care

Introduction to Part I

Sirpa Wrede

For feminist writers of the 1970s, maternity care, with its medicalized and alienating approach to birth, was an apt illustration of women’s oppression by patriarchal social structures. Their critical assessment of the treatment of women at birth led to a blossoming of academic interest in maternity care. Numerous studies were generated, first in Anglo America and somewhat later in other high-income countries. The majority of this early work examined the power relations between physicians, pregnant women, and midwives. As the field developed, research began to present a more complex picture of maternity services, and yet in most studies medical science and the medical profession remained central. Medical science was seen as the source of power for maternity care professionals, allowing hospitals and medical specialists to assume control of the conduct of birth.

This single-minded focus on power relations in maternity care was driven by the close links between researchers and the campaigns to reform birth practices that populated the social landscape when the academic study of maternity care was in its infancy. But the field is maturing. Thirty years after the first feminist exposés of the mistreatment of women at birth, maternity care research is becoming more closely linked to academic disciplines and to ongoing scholarly debates. As a result, new perspectives and new areas of inquiry are emerging. One of the more promising of these is comparative research on the politics of maternity care.

The chapters in this part represent some of the best new work in this area. These studies of the comparative politics of maternity care services present a more complicated, but more accurate, understanding of the way maternal health services emerge and are designed. The comparative data presented here show medical science to be just one among several important actors that influence the form and content of maternity care.

The five chapters in this section approach the politics of maternity care from different angles, but taken together they allow us to draw a shared conclusion: The organization of maternal health services is a contested domain where negotiations and struggles constantly occur. Maternal health services in the present-day societies of 3 North America and Europe result from purposeful designs and are shaped by the actions of multiple groups. No one party, not even the state, has the sole authority to design maternal health services.

The first chapter discusses the issue most central to the organization of maternity services in the twentieth century, the location of birth. Although much discussed in the literature, the topic has not been exhausted and is sorely in need of a perspective drawn from the comparison of developments in different countries. Declercq and his colleagues examine five case studies—the United States, Britain, Finland, the Netherlands, and Norway. The cases exemplify different logics for the organization of birth. The authors show that even though birth in high-income countries generally takes place in large, specialized hospitals, the policy processes that led to this outcome were quite different. Their work also calls attention to maternity policies that run counter to the trend toward centralization. Home birth remains part of the care system in the Netherlands and is being encouraged again in the United Kingdom, while in Norway policymakers are defending small maternity hospitals in rural areas. The variation presented in this chapter—in policy and in the roles of birth attendants and technology— makes clear that it is too early to argue for convergence in the organization of birth in high-income countries. We need more nuanced information about the way care at birth is shaped by different national settings and by different hospitals.

The second chapter focuses on the role of the state in generating variation in maternal health designs. Wrede and her colleagues focus on “critical moments” in maternity health policy. The chapter shows that maternity care has only rarely been at the center of the political arena in the three countries studied (Britain, Canada, and Finland). The authors conclude that state interest in maternity care services generally centers on the same pragmatic interests found in policy questions about other health services. Of course, political currents can, and have, shaped maternity care policy. The British and Finnish cases show how maternity care policies emerged from political concerns about population. In the United Kingdom and Canada we see policymakers responding to the call for “woman-centered” care, and in Finland policymakers have adopted a family-centered approach in an effort to promote, among other things, more equally shared parenthood. In general, however, the organization and transformation of maternal health services have been linked to overall policymaking concerning health care systems.

In Chapter 3 Bourgeault and her colleagues look at the influence of consumer interest groups on maternity care policy. Drawing on research in three countries— Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States—the authors examine the factors that allow consumers to affect maternity policy. Their data suggest that well-organized pressure can make a difference in policy decisions, but they are careful to note the problems and limitations of consumer involvement in policy. Recent events in Canada and the United Kingdom show that effective consumer action requires both access to policymaking arenas and a measure of good luck concerning timing. Furthermore, the authors remind us that consumer groups are not democratic: Like all social organizations, these groups come to develop their own expertise and agendas.

Drawing on ethnographic data from Canada and the United States, Chapter 4 offers another perspective on collective action in maternity care reform. Daviss—an apprentice-trained midwife and a long-time activist in the Canadian alternative birth movement (ABM)—writes a passionate defense of the efforts of the ABM to transform the deeper cultural context of birth. She does not necessarily agree that the introduction of midwifery to the health system in Canada (discussed in Chapter 3) has been a success for the ABM. She fears that insiders in maternal health service policy in Canada—some of whom were members of the ABM—have been co-opted and forced to give up their original goals.

The contrast between the ABM described by Daviss and the pressure groups discussed in Chapter 3 is instructive. Supporters of movements like the ABM are drawn from policy outsiders who are often less interested in influencing public policy than in creating alternative solutions that promote great individual freedom. This (voluntarily chosen) position outside the policy system is possible only for people who can afford—economically and/or culturally—to ignore official services. For the majority of childbearing women and their partners it is difficult, if not impossible, to opt out of the existing system of care.

Interestingly, the stories of the ABM and other consumer pressure groups reveal that collaboration between maternity care providers and users is necessary to promote change in maternity services. In fact, maternity care providers—midwives and obstetrician-gynecologists—often play a central role in this type of social action. Most childbearing women and their partners are only temporarily active in issues surrounding birth, giving providers a chance to become the spokespersons for pressure groups. This provider/user collaboration is striking because the interests of providers and users are often in conflict.

In the last chapter of Part I, Nelson and Popenoe look within countries to examine effects of different policy styles. They show that there is significant intracountry variation in women’s access to maternal health services in high-income countries. The authors illustrate how social categories of class, race/ethnicity, and immigrant status shape women’s access to care in the United States and Sweden. In the United States, these categories play a significant role in the quality of care received, while in Sweden women’s access to maternal health services is barely affected by social identity. Availability of a national maternity service (in Sweden but not in the United States) goes a long way toward explaining these intracountry differences. Universal care is not an unmixed blessing, however. The authors conclude their chapter by examining how the uniformity of maternity care in Sweden poses limits for new immigrants.

These studies of the political and social organization of birth show maternity care systems to be products of a complex of factors. They correct and complicate earlier views of the field and promote a richer understanding of the forces responsible for the delivery of care at birth.

CHAPTER 1

Where to Give Birth?

POLITICS AND THE PLACE OF BIRTH

Eugene Declercq, Raymond DeVries, Kirsi Viisainen, Helga B. Salvesen, and Sirpa Wrede

Introduction

The most significant change in twentieth-century maternity care was the movement of the place of birth from the home to large hospitals. At the beginning of the last century virtually all births occurred at home; by the end of the century almost every woman who gave birth in an industrialized country (with the odd exception of the Netherlands) did so in a hospital. All the other major trends in maternity care that you will read about in this book—the changing status and role of midwives, the increasing use of technological interventions, the developments in maternity care policy, the redefinition of birth—are intimately related to this move from home to hospital. But the most interesting thing about this change in maternity care is that the end result— the (nearly) complete move of birth to the hospital—was achieved in a number of different ways. The decision to hospitalize birth in Finland was made for different reasons than the decision in the United Kingdom or the United States. This variation between countries offers us the perfect opportunity to isolate and examine societal and cultural differences in maternity care policies and practices.

Why should it matter where a baby is born? Simply stated, the place of birth shapes the experience, determining who is in control and the technologies to be employed. In a home birth, those attending are visitors in the family’s domain, and midwives and doctors must rely on the family for an understanding of local customs and practices. The reverse is true for a mother in a hospital. In a hospital birth a mother is placed in a dependent condition reinforced by the use of unfamiliar language and machinery. The place of birth also determines the way care is organized. Birth at home is patterned around the values of the family. In hospitals—where hundreds, or even thousands, of births occur each year—birth is a routine event, accomplished with speed and efficiency.

The hospitalization of birth encourages the use of technologies that can only feasibly be applied in a hospital. As the twentieth century progressed, hospitals became centers where new technologies could be easily tested and then applied to large numbers of women. The concentration of women in one place made the training and staffing needed to maintain the technologies clinically safer and economically feasible; the presence of the latest scientific technologies (e.g., fetal monitors and epidural anesthesia) in hospitals served to enhance their prestige as centers of science.

Hospitalization of birth also has a variety of economic and social consequences. It makes feasible a larger client base for providers, a particularly important issue in those countries whose funding system rewards physicians for the size of their practice. It also eases the demands on providers and allows health planners to make care more “efficient.” Bringing large numbers of patients to a central location is much more economical—for providers and planners—than providing care in homes or in a series of small “cottage hospitals.” If one considers birthing mothers to be economic units, the larger the site, the greater the potential for economies of scale. The irony of this approach is that it often leads to large birthing hospitals also becoming centers of elaborate, and very expensive, technology, the use of which make birth more costly.

Our analysis of this most important change in twentieth-century maternity care continues with a detailed look at five countries: the United States, Finland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Norway. After an overview of the general trend toward hospital births in these countries, we move to in-depth case studies of each.

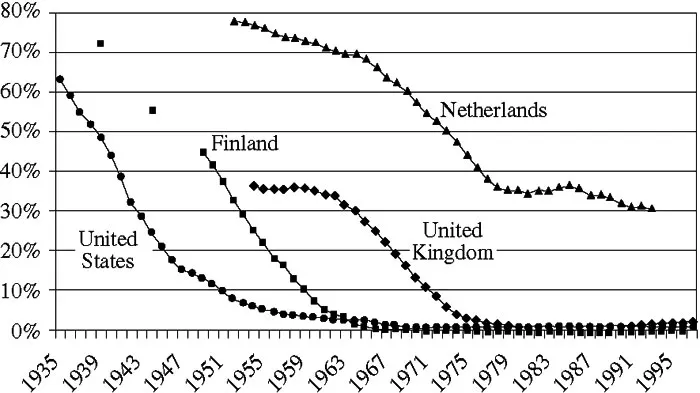

The Movement of Birth from the Home to the Hospital

The movement of birth from home to hospital in the twentieth century follows similar patterns in many industrialized countries, although the change occurs at different times in different places. The United States made the earliest and most rapid shift to hospitalization, with the biggest changes in the late 1930s. By 1954—when data are available for the four countries shown in Figure 1–1—the United States was down to 6 percent non-hospital births; Finland was at 25 percent, the United Kingdom was at 36 percent and the Netherlands was at 77 percent. The pattern in the United Kingdom clearly parallels that in the Netherlands, with the changes occurring at the same time; the Dutch out-of-hospital birth rate from the mid-1950s to the present, however, is approximately 35 percent higher than that of the United Kingdom. Universal (99 percent or more) hospitalization of birth occurred in Finland and the United States by the late 1960s and in all the countries studied in this book (except the Netherlands) by the early 1980s.

The hospitalization of birth parallels the broader movement of health care out of the home and the (more recent) centralization of health services in large medical centers. As hospitals grew—in number and in size—many procedures once done at home were relocated to the hospital (Blom 1988). In the context of this larger move toward the hospitalization of medical ministrations there were several peculiar fac- tors that encouraged women to quit their homes to give birth. The move to hospital birth initially also required a redefinition of hospitals. At the opening of the nineteenth century, “Hospitals [in the United States] were regarded with dread and rightly so. They were dangerous places; when sick, people were safer at home” (Starr 1982, p. 72). In the second half of the nineteenth century, hospitals became the focus of successful reform efforts by both local elites and physician groups.

FIGURE 1–1. Finland, Netherlands, U.K. and U.S. Out-of-Hospital Births, 1935–1997.

Sources: Finnish Data: The official statistics of Finland (Helsinki: National Board of Health); Isterland et al. 1978. Perinataalistatus 1975 (Helsinki); Medical Birth Registry (Helsinki: STAKES). U.K. Data: 2000. British Counts: Statistics of Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2nd ed., vol. 2, tables by A. MacFarlane, M. Mugford, J. Henderson, A. Furtado, J. Stevens, and A. Dunn (London: The Stationary Office). U.S. Data: 1979. Devitt N. Hospital birth vs. home birth: The scientific facts past and present. In Compulsory Hospitalization or Freedom of Choice in Childbirth?, vol. 2, ed. D. Stewart and L. Stewart (Marble Hill, Missouri: NAPSAC):

A third factor that helped to move maternity care into hospitals was a redefinition of birth as illness. In the early part of the twentieth century, childbirth was increasingly described as a dangerous malady requiring specialized care that could only be provided in the now “safe” hospital. Abetting this process was the development of anesthetics that were best administered in a hospital.

Finally, the movement of birth to the hospital served the campaign of physicians to undercut the status of midwives. Physician groups saw midwives as a threat to their status, especially in those countries where an attempt was being ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Introduction: Why Maternity Care Is Not Medical Care

- Part I: The Politics of Maternity Care

- Part II Providing Care

- Part III Society,Technology, and Practice

- Appendix The Politics of Numbers

- Contributors