![]()

Section III

Understanding Progress and Continuing Challenges in American Higher Education

![]()

8

Trends in the Education of Underrepresented Racial Minority Students

Peter Teitelbaum

Introduction

Higher education often has the profound ability to increase social and economic capital and serve as a tool of social mobility. Moreover, many studies find that Americans need an advanced degree to enter high-paying and/or prestigious occupations in the twenty-first century (Bowen and Bok 2002; Day and Newburger 2002; Swail 2000; Vernez et al. 1999). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, average earnings in 2000 ranged from $18,900 for high school dropouts to $25,900 for high school graduates. College graduates earned an average of $45,400, while those with professional degrees (M.D., J.D. , D.D.S., or D.V.M.) earned $99,300. Over a lifetime, the projected variation in earnings by educational attainment ranged from $1.2 million for high school graduates to $2.1 million for college graduates and $4.4 million for those with professional degrees (Day and Newburger 2002).

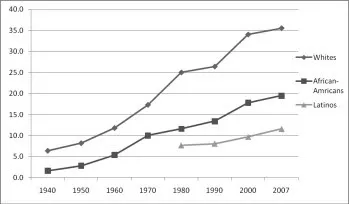

Underrepresented minorities have made tremendous gains in educational attainment over the past seventy years. But the educational gap between Whites and underrepresented minorities, particularly between Whites and Latinos, remains wide. For example, 94 percent of Whites and 88 percent of African Americans who are between the ages of 25 and 29 had graduated from high school by 2007, compared to only 65 percent of Latinos. For four-year college graduation rates, the gap between White students and both Black and Latino students remains substantial. In 2007, 35.5 percent of Whites, 19.5 percent of African Americans and only 11.6 percent of Latinos between the ages of 25 and 29 had a bachelor’s degree (U.S. Department of Education 2008, table 8)

These educational disparities also affect workforce participation and earnings. On average, African American and Latino families earn less than two-thirds of what their White counterparts earn (U.S. Census Bureau 2001). As a result, underrepresented minority families have less disposable income to save and invest in their own or their children’s personal development.

This chapter will examine underrepresented minorities’ experiences in higher education between 1940 and 2007 as well as their ability to earn advanced degrees and to obtain high-paying occupations.1

Historical Context of Underrepresented Minorities’ Educational Experiences

In the 1940s, most African Americans were poor, lived in rural communities in the South, and received a far inferior education than Whites. According to Card and Krueger (1992), African American children attended schools that served predominately African Americans, and these schools afforded substandard academic opportunities compared to schools that were predominately White. For example, African American teachers earned less than half of the salaries of their White counterparts, the school year was shorter, and the average class size was larger. As a result, in 1940, among Americans who were 25 to 29 years old, Whites were more than three times more likely to graduate from high school or earn a bachelor’s degree than African Americans. That is, in 1940, the percentages of 25- to 29-year-old Whites completing high school and college were 24.2 and 5.9 respectively, compared to only 6.9 and 1.4 percent of African Americans. (U.S. Department of Education 2008, table 8). (Between 1940 and 1975, no information regarding the educational attainment or earnings of Latinos was collected by the U.S. Departments of Census or Edu-cation; therefore, this chapter will only address the educational and labor market experiences of Whites and African Americans before 1975.)

In the mid 1940s, World War II initiated an unprecedented demand for factory labor, resulting in a migration of African Americans to the North. The economy continued to grow through the 1950s, and the educational conditions for African Americans improved substantially. In fact, the average teachers’ pay and the length of the school year among secondary schools that served primarily African American students became similar to those schools serving predominately White students, and the disparity in average class size declined over this 20-year period (Card and Krueger 1992). Similarly, the difference in the likelihood that Whites and African Americans would earn high school and bachelor’s degrees decreased between 1940 and 1960. The percent of 25- to 29-year-old Whites and African Americans who graduated from high school increased to 63.7 and 38.6 percent respectively (from 24.2 and 6.9 percent in 1940), while 11.8 percent of Whites and 5.4 percent of African Americans between the ages of 25 and 29 years old had earned bachelor’s degrees in 1960 (from 5.9 and 1.4 percent in 1940) (U.S. Department of Education 2008). In 1960, 25- to 29-year-old Whites were only twice as likely as African Americans to have earned bachelor’s degrees, compared to four times as likely in 1940.

Figure 8.1 The Percentage of 25- to 29-Year-Old Whites, African Americans and Latinos Who Earned a Bachelor’s Degree between 1940 and 2007

Source: U.S. Department of Education 2008, table 8.

The Civil Rights Movement intensified during the 1960s and 1970s and contributed substantially to the improved access to higher education for racial minorities. In 1961, freedom riders from the North took buses to the deep South to protest segregation in schools. A federal judge ordered the University of Mississippi to admit an African American student in 1962, and, in the following year, Governor George Wallace incited a riot as he attempted to prohibit two African American students from attending the last all-White state university, the University of Alabama. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, formally engaging the federal government to dismantle segregation. Moreover, President Johnson called for schools to move beyond nondiscrimination and promote affirmative action in his 1965 commencement speech at Howard University in which he stated: “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line in a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair” (Rainwater and Yancey 1967).

In the 1960s and early 1970s, most leading selective colleges developed programs to increase the number of underrepresented minority students on their campuses, taking race into account in the admissions process. This impacted college-going rates for students of color. By 1975, the percent of 25- to 29-year-old Whites, African Americans and Latinos who earned a bachelor’s degree was reported to be 23.8, 10.5 and 8.8 percent respectively (U.S. Department of Education 2008).

The 1978 Supreme Court ruling in Bakke proscribed the use of race in admissions but affirmed that admissions officers could “take race into account” as one of several factors in evaluating the merits of minority applicants compared to other candidates as a means to secure the benefits of a student body of diverse backgrounds and experiences (438 U.S. 265, 1978). After the Supreme Court ruling, and through the mid-1990s, most selective colleges continued to consider race in admitting students, sometimes adjusting their policies and practices to comply with the Court’s decision. Between 1960 and 1995, the percent of 25- to 29-year-old African Americans who earned a bachelor’s degree increased by almost three-fold, from 5.4 percent to 15.4 percent. Surprisingly, there were almost no gains in the percentage of 25- to 29-year-old Latinos who earned a bachelor’s degree between 1975—the earliest year for which the U.S. Department of Education collected educational attainment data for Latinos—and 1995 (from 8.8 to 8.9 percent over that 20-year span).

In the mid-1990s, a major court decision in Texas and Proposition 209 in California signaled a shift in attitudes against affirmative action admissions policies. In the summer of 1995, the Regents of the University of California University System announced that the state system would no longer be permitted to take race into account in admitting students. A year later, California voters approved Proposition 209 which effectively outlawed affirmative action in California. In that same year, 1996, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit heard the case of Hopwood v. Texas. The Court ruled that the University of Texas Law School could not take race into consideration in admitting students unless such action was necessary to remedy past discrimination by the school itself (78 F.3d 932).

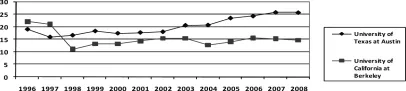

At the University of California at Berkeley, the freshman class of 1998 was the first to feel the impact of Proposition 209. The number of Black freshmen who enrolled at the school dropped by over 50 percent in just one year, from 258 in 1997 to 126 students in 1998, and the number of Latino freshmen declined from 476 to 272 students. In 1997, 20.5 percent of the freshman class at the University of California at Berkeley was African American or Latino. In 1998, this figure was just 10.7 percent (University of California 2008). At the University of Texas at Austin, the freshman class of 1997 was the first to experience the influence of the Hopwood decision. The percentage of the freshman class at the University of Texas

Figure 8.2 The Percentage of the Freshman Class That Was African American, Latino or Native American at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of California at Berkeley between 1996 and 2008

at Austin that was African American dropped from 4.1 to 2.7 percent from 1996 to 1997—a 34 percent decrease. Latino students were less affected by the Hopwood case; the percentage of the freshman class that was Latino dropped 13 percent, from 14.5 to 12.6 percent between 1996 and 1997 (University of Texas 2008).

Legal and political decisions regarding race and admissions have had varying influences on minority enrollment. While the Hopwood case did adversely affect the racial/ethnic composition of the freshman class at University of Texas at Austin for several years, the Texas 10 percent rule—which was implemented in 1999 and states that students who graduated among the top 10 percent of their high school class are guaranteed admission to public universities in Texas—helped the University recruit qualified underrepresented minorities. According to Long and Tienda (2008), minority enrollment was increased due to the new policy. For example, Latinos and African Americans account for 19.9 and 5.6 percent respectively of the 2008 freshman class at the University of Texas at Austin—higher percentages than in 1996 (University of Texas 2008). At the University of California at Berkeley, Latino students have experienced large enrollment gains since 1997; nevertheless, their enrollment rates are still lower than before Proposition 209 took effect (13.3 percent of the freshman class in 1996, 7.3 percent in 1997, and 10.9 percent in 2008). In contrast, the African American enrollment rate for the freshman class at the University of California at Berkeley has not changed since the Proposition took effect in 1997and remains at 3.4 percent in 2008 (University of California 2008).

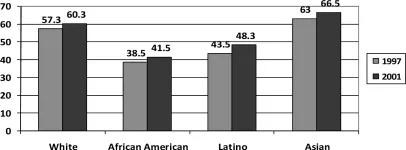

Student Persistence in College

Affirmative action politics tends to target admissions, and, where race-sensitive admissions programs have been in place, there has been an increase in the proportion of underrepresented minorities that have enrolled in college over the past half century. However, once underrepresented minority students are on college campuses, it is also important to ensure that they remain in college and earn a degree. The evidence regarding postsecondary persistence for underrepresented minorities is mixed. Although graduation rates have increased for all racial/ethnic groups between 1997 and 2001, attrition rates still vary substantially by race. Among the students who enrolled in four-year institutions as freshmen during the 2001–02 academic year, only 57.3 percent earned a bachelor’s degree within six years (NCES 2009). A breakdown of the graduation data by race reveals that more than 3 out of every 5 Asian (66.5 percent) or White (60.3 percent) students graduated within six years, compared to less than half of Latino (48.3 percent) and African American (41.5 percent) students. While the graduation rates for Latinos increased by 5 percent between 1997 and 2001, the graduation rates for African Americans increased by only 3 percent.

Attrition can have long-term consequences for both students and institutions. The two most important benefits of earning a college degree are (1) the

Figure 8.3 The Percentage of Students Who Enrolled as Freshman in four-year, Title IV Institutions in the 1997 and 2001 Academic Years and Graduated within Six Years, by Race

Source: National Center for Education Statistics (2005 and 2009).

opportunity for economic and social mobility and (2) the ability to pursue an advanced degree. Students who leave school without a degree—particularly socioeconomically disadvantaged students who are disproportionately likely to be underrepresented minorities—often depart with substantial debt. Not only does this adversely affecting their credit rating (Swail 2003), but the lack of a bachelor’s degree also results in poorer employment prospects. Among students who enrolled in college, those who failed to complete any degree earn on average about $32,000 a year, compared to $33,000 for students who obtained an associate’s degree and $45,400 for students with a bachelor’s degree (Day and Newburger 2002). According to Bowen (1980), Pascarella and Terenzini (1991), Adelman (1999) and Bowen and Bok (2002), students who persist in college are more likely to have intellectually stimulating experiences as well as participate in social and cultural events than those who leave. Moreover, the long-term benefits of completing a bachelor’s degree include higher lifetime earnings, a better work environment, improved access to professional development and a lower probability of unemployment. Finally, only students with a bachelor’s degree will have the opportunity to enroll in advanced degree programs that may allow them to obtain a prestigious and high-paying occupation.

Advanced Degrees and High-Paying Occupations

Although underrepresented minorities made large gains in terms of the percentage of people who have earned high school and college degrees since 1940, the representation of African Americans and Latinos in higher education declines as the degree level increases. For example, while African Americans earned 8.1 percent of all bachelor’s degrees awarded in 1996–97, they only earned 6.8 percent of all master’s degrees, 6.7 percent of all first-professional degrees, and 4.1 percent of all doctorate degrees received that year. Similarly, Latinos earned 5.3 percent of all bachelor’s degrees, but only 3.7 percent of all master’s degrees, 4.6 percent of...