![]()

PART 1

Archaeology

![]()

1. Gender:

In the Academy

and the whole of beauty consists, in my opinion, in being able to get above singular forms, local customs, particularities, and details of every kind.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourses on Art

A Folly! Singular & Particular Detail is the Foundation of the Sublime.

William Blake, Annotations to Reynolds’s Discourses

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Is the detail feminine? This question assumes a certain urgency when one recalls that one of the major debates in neo-classical aesthetics—whose legacy is still very much with us today—concerns precisely the status of the detail in representation, the practice of what I will call, after G. H. Lewes, “detailism.”1 According to Ernst Cassirer, “the problem of the relationship between the general and the particular” is “the basic and central question of classical aesthetics.”2 Nowhere is the problem more insistently foregrounded than in a work generally recognized as one of the most considerable and representative bodies of Academic aesthetics produced in Europe in the latter half of the eighteenth century, the Discourses on Art which Sir Joshua Reynolds delivered to the “Gentlemen”—Reynolds’s addressees are definitely, exclusively male—of the Royal Academy between 1769 and 1790.3

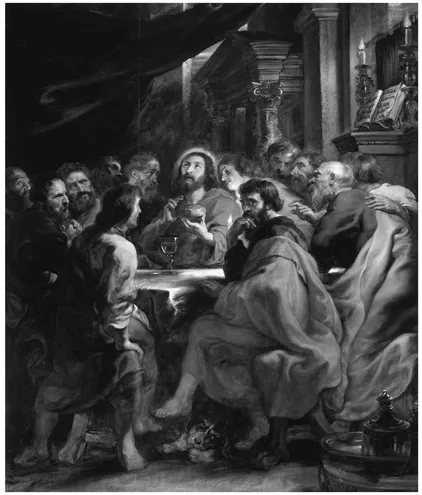

Before turning to Reynolds’s Discourses, I would like to make a brief reference to a lesser-known text of Reynolds’s, indeed his only sustained work of practical art criticism: A Journey to France and Holland. In 1781, Reynolds travelled through the Low Lands, recording his impressions of the numerous paintings he saw in the churches and private collections he visited. Commenting on a Last Supper by Rubens, then hanging in the Cathedral at Mechlin, Reynolds notes:

Under the table is a dog gnawing a bone; a circumstance mean in itself, and certainly unworthy of such a subject, however properly it might fill a corner of such a picture as the marriage of Cana, by Paul Veronese.4

I take this passing note as exemplifying Reynolds’s general aesthetic stance. The painter’s practiced gaze is immediately drawn to a corner of the painting before him, to a trivial detail which is distinctly out of place in the lofty scene represented. Thus in one glance are conjoined the most traditional separation of high and low subjects and a thoroughly modern, not to say postmodern, fascination with the eccentric detail, referring to the refuse, so to speak, of everyday life.

As we turn now to Reynolds’s Discourses, we shall do well to bear this vignette in mind, for it bodies forth the dual attitude toward the circumstantial which pervades the Discourses; as M. H. Abrams notes, Reynolds’s aesthetics are bipolar,5 oscillating between a strict anti-detailism consonant with classical Academic discourse, and a lucid recognition of the uses of particularity in keeping with the contemporary rise of realism. Nevertheless, as Abrams is quick to recognize, the general pole of Reynolds’s aesthetics predominates over the other, the particular. My concern in what follows is with the logic of the discourse marshalled against the detail.

Summarizing Sir Joshua’s general system “in two words” William Hazlitt writes: “That the great style in painting consists in avoiding the details and peculiarities of particular objects.”6 Reynolds’s censure of the detail is not quite as absolute as Hazlitt’s summary suggests, but it persists throughout the discourses. It dominates in particular the Eleventh Discourse, which Reynolds himself outlined as follows in the Table of Contents: “Genius—Consists principally in the comprehension of A WHOLE; in taking general idea only.”7 Indeed the entire discourse on Genius takes the form of a protracted and sinuous argument against confusing detailism and Genius: “a nice discrimination of minute circumstances, and a punctilious delineation of them, whatever excellence it may have, (and I do not mean to detract from it,) never did confer on the Artist the character of Genius” (XI, 192). Whereas the second-rate artist loses himself in the servile copying of nature in its infinite particularity, the Genius extends his “attention at once to the whole.”

The opposition of Genius and second-rate artist corresponds to a distinction Reynolds draws elsewhere between two forms of mimesis. There are, he writes in his annotations to a translation of Du Fresnoy’s poem, The Art of Painting, “two modes of imitating nature; one of which refers for its truth to the sensations of the mind, and the other to the eye.”8 Not only is the purely visual form of mimesis inferior, worse it is regressive, for it produces a trompe l’oeil effect which harks back to the infancy of painting: “Deception, which is so often recommended by writers on the theory of painting, instead of advancing art, is in reality carrying it back to its infant state.”9 For whereas poetry in its primitive state eschewed the representation of the common life in favor of the supernatural and the extraordinary (“heroes, wars, ghosts, enchantment and transformation”), painting began by showing off its capacity to transform indifferent objects into seemingly three-dimensional figures capable of fooling even the canniest observers. This archaic stage of

Figure 2. Rubens, Last Supper

painting might be described as the birds and grapes stage, in reference to Pliny’s oft-cited anecdote about art and illusion in classical antiquity.

The story runs that Parrhasios and Zeuxis entered into competition, Zeuxis exhibiting a picture of some grapes, so true to nature that the birds flew up to the wall of the stage. Parrhasios then displayed a picture of a linen curtain, realistic to such a degree that Zeuxis, elated by the verdict of the birds, cried out that now at last his rival must draw the curtain and show his picture.

Figure 3. Veronese, Marriage at Cana

On discovering his mistake he surrendered his prize to Parrha-sios, admitting candidly that he had deceived the birds, while Parrhasios had deluded himself, a painter.10

Reynolds’s strictures against detailism fall into two distinct groups which must be clearly distinguished if the subsequent destiny of the detail as aesthetic category is to become intelligible: on the one hand there are the qualitative arguments (those according to the Ideal), on the other the quantitative (those according to the Sublime). In the first instance, Reynolds argues that because of their material contingency details are incompatible with the Ideal; in the second he argues that because of their tendency to proliferation, details subvert the Sublime. But while the rise of realism will entail the legitimation of the contingent detail, it will remain to modernity to embrace the dispersed detail.

Let us pay close attention to his use of language. For though Reynolds himself was an outspoken believer in the instrumental nature of language—“Words should be employed as the means, not as the end: language is the instrument, conviction is the work” (IV, 64)—his writing is laced with figures, notably extended metaphors. The following passage from the Third Discourse provides us not only with one of Reynolds’s most fully articulated statements on the difference between the particular and the general, but also with one of the most elaborate deployments of his metaphorics of the detail:

All the objects which are exhibited to our view by nature, upon close examination will be found to have their blemishes and defects. The most beautiful forms have something about them like weakness, minuteness, or imperfection. But it is not every eye that perceives these blemishes. It must be an eye long used to the contemplation and comparison of these forms; and which, by a long habit of observing what any set of objects of the same kind have in common, has acquired the power of discerning what each wants in particular. This long laborious comparison should be the first study of the painter, who aims at the greatest style. By this means, he acquires a just idea of beautiful forms; he corrects nature by herself, her imperfect state by her more perfect. His eye being able to distinguish the accidental deficiencies, excrescences, and deformities of things, from their general figures, he makes out an abstract idea of their forms more perfect than any one original; and what may seem a paradox, he learns to design naturally by drawing his figures unlike any one object. This idea of the perfect state of nature, which the Artist calls the Ideal Beauty, is the great leading principle, by which works of genius are conducted. (III, 44–45; emphasis added)

The “selection” procedure Reynolds recommends the painter follow in abstracting the Ideal from brute Nature is not unlike the technique devised by structuralist analysts of myth and folktales to extract the invariant structure of the narrative from its variable concrete manifestations. The ideal, like the Structure, is a construct arrived at by conceptual rather than perceptual means. But what differentiates the contemporary structuralist from the eighteenth-century idealist is their use of language: whereas the language of the structuralist strives toward objectivity in the manner of a pseudoscientific discourse, in this characteristic treatise of Augustan aesthetics the metaphorics of the detail is heavily freighted with the vocabulary of teratology, the science of monsters. In its unreconstructed state, nature is a living museum of horrors, a repository of genetic aberrations, which can take the form either of lack (deficiencies) or excess (excrescences)—the logic of the particular is the logic of the supplement. The particular becomes a vehicle for pollution; to practice naive mimeticism is to risk introducing the Impure into the space of representation, for as Reynolds writes in his Third Paper for The Idler: “if it has been proved that the Painter, by attending to the invariable and general ideas of Nature, produce beauty, he must, by regarding minute particularities, and accidental discrimination, deviate from the universal rule, and pollute his canvass with deformity.”11

Deformity is the key word in Reynolds’s qualitative argument against the particular. It is through his insistent use of the word that we begin to grasp the link between particularity and the feminine. For though Reynolds never explicitly links details and femininity, by taking over a metaphorics grounded in metaphysics—and Reynolds’s debt to both Plato and Aristotle is well-documented—he implicitly reinscribes the sexual stereotypes of Western philosophy which has, since its origins, mapped gender onto the form-matter paradigm, forging a durable link between maleness and form (eidos), femaleness and formless matter. This equation pervades Greek theories of reproduction, notably Aristotle’s. According to his founding myth of sexual difference, woman’s sexual desire only serves to confirm her lack: “matter longs for form as its fulfillment, as the female longs for the male.”12 As this passage illustrates, the always imperfect nature which awaits the (male) artist’s trained eye to attain the beauty of the Ideal is in the idealist tradition in which Reynolds participates, feminine. “He corrects nature by herself,” writes Reynolds, revealing the pedagogical role of the male artist who cunningly instructs female Nature by homeopathic means.

The alignment of woman and (devalorized) nature is, of course, not limited to classical metaphysics or neo-classical aesthetics; it is, according to anthropologist Sherry Ortner, a universal phenomenon. The relationship of woman and nature is, Ortner emphasizes, one of proximity rather than identity. Women are viewed cross-culturally as closer to nature than men, who are associated with the more prestigious term, culture, that is anti-physis. Ortner lists three reasons for linking woman and nature: woman’s physiology (childbearing); woman’s social role (childrearing), and woman’s psyche. Both as a social being and an individual, woman is seen as more embedded in the concrete and the particular than man:

the family (and hence woman) represent lower-level, socially fragmenting, particularistic sort of concerns, as opposed to inter-familial relations representing higher-level, integrative, universal-istic sort of concern.

One relevant dimension that does seem pan-culturally applicable is that of relative concreteness vs. relative abstractness: the feminine personality tends to be involved with concrete feelings, things, and people, rather than with abstract entities; it tends toward personalism and particularism.13

The unchallenged association of woman and the particular spans not only cultures, but centuries, extending from antiquity to the present day; along the way, however, it has acquired the trappings of scientific fact, and it is on this semimythical, semiscientific association that modern-day critics have based their assessments of men’s and women’s respective contributions to the arts. Thus Jean Larnac, the author of the classical Histoire de la littérature féminine en France (1929), grounds his unshakeable belief in the absolute difference between men’s and women’s writing on what must have passed in his time for the latest in scientific evidence. According to one Iastrow, writes Larnac, it has been shown that: “while female students are attentive to their immediate surroundings, the finished product, the decorative, the concrete, the individual, men prefer what is most distant, the constructive, the general and the abstract.”14 Viewed as congenitally (rather than culturally) particularistic, the woman artist is doubly condemned to produce inferior works of art: because of her close association with nature, she cannot but replicate it. The law of the genre is that women are by nature mimetic, incapable of creating significant works of ...