1

Urban Geography

from global to local

Preview: the study of urban geography; global triggers of urban change—economy, technology, demography, politics, society, culture, environment; globalisation; localisation of the global; the meaning of geographic scale; local and historical contingency; processes of urban change; urban outcomes; why study urban geography?

INTRODUCTION

Urban geography seeks to explain the distribution of towns and cities and the socio-spatial similarities and contrasts that exist between and within them. If all cities were unique, this would be an impossible task. However, while every town and city has an individual character, urban places also exhibit common features that vary only in degree of incidence or importance within the particular urban fabric. All cities contain areas of residential space, transportation lines, economic activities, service infrastructure, commercial areas and public buildings. In different world regions the historical process of urban evolution may have followed a similar trajectory. Increasingly, similar processes, such as those of suburbanisation, gentrification and socio-spatial segregation, are operating within cities in the developed world, in former communist states and in countries of the Third World to effect a degree of convergence in the nature of urban landscapes. Cities also exhibit common problems to varying degrees, including inadequate housing, economic decline, poverty, ill health, social polarisation, traffic congestion and environmental pollution. In brief, many characteristics and concerns are shared by urban places. These shared characteristics and concerns represent the foundations for the study of urban geography. Most fundamentally, the character of urban environments throughout the world is the outcome of interactions among a host of environmental, economic, technological, social, demographic, cultural and political forces operating at a variety of geographic scales ranging from the global to the local.

In this book we approach the study of urban geography from a global perspective. This acknowledges the importance of macro-scale structural factors in urban development, but also recognises the reciprocal relationship between global forces and locally contingent factors in creating and recreating the geography of towns and cities. A global perspective also demonstrates the interdependence of urban places in the contemporary world, and facilitates comparative urban analysis by revealing common and contrasting features of cities in different cultural regions. This global perspective resonates with recent transnational1 and postcolonial 2 approaches to urban study. The global perspective eschews the analytical value of simplistic distinctions between cities based on, for example, level of development; rejects prioritisation of knowledge produced in one world region or city over another; and seeks to understand cities by drawing on the richness and diversity of urban experience that characterises our contemporary urban world.

While the organisation of this book into sections and chapters is a necessary pedagogic device to bring order to the complex and diverse subject matter of urban geography, the global perspective underlines the interconnections among the different sections, chapters and themes presented. In addition, the global perspective not only promotes integrated insight into our urban world but also encourages readers to ‘think outside the box’ and seek to relate experiences across different urban and cultural realms.

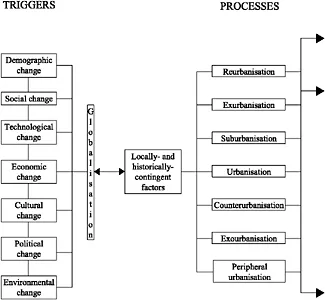

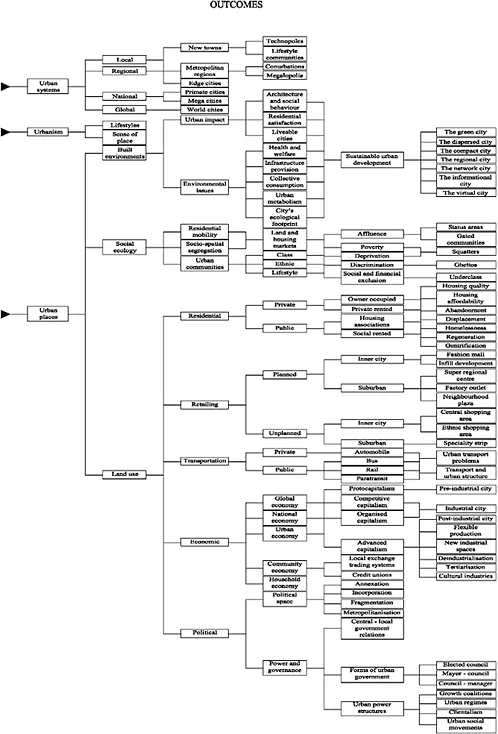

The framework we shall employ in our study of urban geography is depicted in Figure 1.1. In reading from left to right, we move from the global to the local scale. This schematic diagram highlights the major ‘trigger factors’ and processes underlying contemporary urban change (Fig 1.1a), as well as the principal urban outcomes of these processes (Fig 1.1b). In this chapter we examine the nature of these factors and processes, and the relationship between global and local forces in the construction of contemporary urban environments.

GLOBAL TRIGGER FACTORS

THE ECONOMY

Economic forces are regarded as the dominant influence on urban change. Since its emergence in the sixteenth century, the capitalist economy has entered three main phases. The first phase, from the late sixteenth century until the late nineteenth century, was an era of competitive capitalism characterised by free-market competition between locally oriented businesses and laissez-faire economic (and urban) development largely unconstrained by government regulation. In the course of the nineteenth century the scale of business increased, consumer markets expanded to become national and international, labour markets became more organised as wage-rate norms spread and government intervention in the economy grew in response to the need for regulation of public affairs. By the turn of the century these accumulated trends had culminated in the advent of organised capitalism. The dynamism of the economic system—the basis of profitability—was enhanced in the early decades of the twentieth century by the introduction of Fordism. This economic philosophy was founded on the principles of mass production using assembly-line techniques and ‘scientific’ management (known as Taylorism), together with mass consumption fuelled by higher wages and high-pressure marketing techniques. Fordism also involved a generally mutually beneficial working relationship between capital (business) and labour (trade unions), mediated by government when necessary to maintain the health of the national economy.

The third and current phase of capitalism developed in the period following the Second World War. It was marked by a shift away from industrial production towards services (particularly financial services) as the basis of profitability. Paradoxically, the explanation for this shift lay in part with the very success of Fordism. As mass markets became saturated, and profits from mass production declined, many enterprises turned to serve specialised ‘niche markets’. Instead of standardised production, specialisation required flexible production systems. This current phase of capitalism is referred to as advanced capitalism or disorganised capitalism (to distinguish it from the organised nature of the Fordist era). The transition to advanced capitalism was accompanied by an increasing globalisation of the economy in which transnational corporations (TNCs) operated often beyond the control of national governments or labour unions (see Chapter 14).

Figure 1.1a Triggers, processes and outcomes in urban geography

The evolution of the capitalist economy is of fundamental significance for urban geography, since each new phase of capitalism involved changes in what was produced, how it was produced and where it was produced. This meant that ‘new industrial spaces’ (based, for example, on semiconductor production rather than shipbuilding) and new forms of city (such as a technopole instead of a heavy industrial centre) were required.3

TECHNOLOGY

Technological changes, which are integral to economic change, also influence the pattern of urban

growth and change. Innovations such as the advent of global telecommunications have had a marked impact on the structure and functioning of the global economy. This is illustrated by the new international division of labour in which production is separated geographically from research and development (R&D) and higher-level management operations, while almost instantaneous contact is maintained between all the units in the manufacturing process, no matter where in the world each is located.

The effects of macro-level technological change are encapsulated in the concept of economic long waves or cycles of expansion and contraction in the rate of economic development (see Chapter 14). The first of these cycles of innovation (referred to as Kondratieff cycles) was based on early mechanisation by means of water power and steam engines, while the most recent (and still incomplete) cycle is based on micro-electronics, digital telecommunications, robotics and biotechnology. The different technology eras represented by Kondratieff cycles shape not only the economy but also the pace and character of urbanisation and urban change. Modification of the urban environment occurs most vigorously during up cycles of economic growth. Technological changes that directly affect urban form also occur at the local level. Prominent examples include the manner in which advances in transportation technology promoted suburbanisation (see Chapter 7) or how the invention of the high-speed elevator facilitated the development of skyscrapers in cities such as New York.

DEMOGRAPHY

Demographic changes are among the most direct influences on urbanisation and urban change. Movements of people, into and out from cities, shape the size, configuration and social composition of cities. In Third World countries expectations of improved living standards draw millions of migrants into cities (see Chapter 23), while for many urban dwellers in the West the ‘good life’ is realised through suburbanisation or exurbanisation. The condition of the urban environment can also affect the demographic structure of cities by influencing the balance between rates of fertility and mortality. Intra-urban variations in health are pronounced in Third World cities where well above-average mortality rates are recorded in overcrowded squatter areas (see Chapter 27), but socio-spatial differences in health status are also characteristic of many Western cities. Demographic changes are related to other ‘trigger factors’ such as economic growth or decline, and political change. For example, population growth in a Third World country may induce political attempts to restrict migration, whether within the country to control ‘overurbanisation’ or between countries, as along the Mexico–USA border.

POLITICS

Cities reflect the political ideology of their society. The urban impact of political change is demonstrated by the case of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (see Chapter 5). During the middle fifty years...