![]()

Part B

Drawing Battlelines Over Language

In Part A we examined the contemporary state of Chinese studies from the point of view of learning and teaching Chinese. While this account of the ‘state of the art’ did involve some discussion of the historical roots of the current situation, especially in Chapter 2 on different language teaching paradigms, it is in Part B that we will focus specifically on the different historical traditions that have fed into Chinese studies, this time from the point of view of the analysis of language, i.e. linguistics. Over the last century and a half of the development of modern Chinese studies (see Honey 2001 for an account of the origins and development of its ‘philological’ traditions), at least three overlapping divisions have emerged which are still current and relevant to an understanding of ideas about language in the field. First there is a division between the ‘old-fashioned’ sinology and the Area studies which ‘replaced’ it (and which is now becoming ‘old-fashioned’ in its turn); next there is a division between the philological text-based approach characteristic of sinology and the social science methodologies which ‘superseded’ it (with a similar disclaimer); and finally there is a division between what could be broadly characterised as a ‘humanistic’ approach towards the Chinese language and the ‘scientific’ linguistic methodologies that exist in an uneasy truce with it. These divisions are not always recognised by those studying or working in the field of Chinese studies, and certain scholars do of course operate across these divisions, but they still determine to a significant extent where one positions oneself in the field.

We start off in Chapter 4 by looking at what is perhaps the most obvious manifestation of these divisions, the phenomenon I have dubbed ‘character fetishisation’, by examining arguments within Chinese studies over just how important Chinese characters are in the understanding of Chinese language and culture, arguments that go beyond linguistics to literary theory, philosophy and even history. Chapter 5 goes back in time, first to the late 1930s and then to the early 1960s, to examine a couple of debates that in effect aimed to define the nature of the field: the first debate specifically over the nature of characters and whether it was sound or meaning that was more important in their creation and interpretation; the second not focused on the characters as such but regarding them, explicitly or implicitly, as crucial in marking off the study of China from that of other parts of the world.

Chapter 6 shifts to scholarship on language in China itself from the late nineteenth century. The sheer inertia of Chinese tradition under the late Empire seemed to be dragging the country close to destruction, and this sparked radical proposals for a wholesale rejection of the Chinese cultural inheritance, including the language and its writing system, in favour of Western imports. Such extreme solutions brought in their turn conservative reactions, and the pull between full-scale adoption of Western concepts and technologies and their wholesale rejection continues to the present day. In the case of linguistics, the inextricably mixed nature of modern Chinese linguistics as a hybrid of native Chinese and imported Western traditions has caused and continues to cause significant ideological as well as practical problems for the understanding and use of Chinese. This chapter also picks up on some ideas put forward during one of China’s key modernising periods in the 1910s and 1920s for Chinese characters to be discarded, and discusses some of the ideological issues involved in more recent revivals of those ideas.

Multilingual polity

![]()

4

Character Fetishisation

The Modus Operandi of Orientalism in Chinese Studies

Introduction: The Historical Background to Orientalism in Chinese Studies

The kinds of discourses to be explored in this chapter are commonly characterised, using the coinage of scholar Edward Said (1978), as orientalism: that is, cross-cultural ideological constructs involved in the (mis)representation of the ‘East’ by the ‘West’. Such claims have deep historical roots, and may also operate in reverse, a process more recently dubbed ‘occidentalism’ (Buruma and Margalit 2004). Before we plunge into the discussion of how this phenomenon shows up in contemporary Chinese studies, it would be useful to get a flavour of these discourses and the historical background to their emergence. Below I present three extracts from three different kinds of ‘travellers’ accounts’ which identify some of the common themes in such discourses, and hint at some of the reasons for the reluctance of many Western – and Chinese – scholars to treat things Chinese as on a par with other languages and cultures.

The first extract comes from a late nineteenth-century work by a missionary scholar as part of a chapter on ‘Western Opinions’ on the Chinese language, in which the author includes, seemingly indiscriminately, speculations on the descent of the Chinese race from one or other of the sons of Noah alongside scholarly discussions on the relationship of the Chinese language to the languages of Tibet and Assam:

[T]he language and literature of China can never among people remote from that country arouse any enthusiastic interest such as that with which some of the Semitic and Indo-European languages have been studied by western scholars. … It cannot be maintained, however, that the language and literature of China have failed to arouse the interest of Western students.

Nor should we expect it to be otherwise, as least as to the language, when we think on its nature and the way in which it is written, so unlike all that we are familiar with in other languages … . [I]t was not until about the end of the sixteenth century that important and authentic information about China and its language began to be acquired by European scholars, and the works written by these show how the language puzzled and enchanted them. One of its great charms for them at first seems to have been found in its written characters.

(Watters 1889: 2)

We may note that, among the aspects of Chinese culture that ‘charmed’ Europeans, the ‘way in which [Chinese] is written’ is singled out for special mention, something that has been a prominent theme in European discussions of China since the pioneering accounts of the Jesuit missionaries started to trickle back from China in the early seventeenth century.

Philosopher Chad Hansen identifies the other side of this exoticism, a kind of ‘excuse’ for the strangeness of Chinese thinking, which earlier scholars of China, commonly known as sinologists, had dubbed ‘Chinese logic’:

Talk about ‘Chinese logic’ emerged in a much earlier generation of sinologists. It is charitable to assume that it was initially motivated by a sincere effort to understand … [by] giving rationales for Chinese philosophical doctrines. But the doctrines themselves often appeared so bizarre (especially to the missionary generation of interpreters) that they could be characterized as reasonable only if logic were suspended or altered beyond our normal recognition … . So ‘special logic’ was originally thought of as a descriptive claim with a frankly racist content: people who are racially Chinese have different (and incommensurable) dispositions to draw conclusions from premises. The special logic claim was used to demand tolerance from Westerners who found Chinese philosophical theories – in a word which has become almost a specialized vocabulary item for things Chinese – inscrutable. Saying Chinese were illogical had a dual effect. It allowed us both to acknowledge our inability to understand the ideas and yet to regard those ideas as a ‘profound’ alternative to our own world view.

(Hansen 1983: 10–13)

Hansen notes that the metaphor of ‘inscrutable’, literally ‘unable to be interpreted’ and often applied in the first instance to facial expressions, has been so often applied to the case of China as to become a stereotypical description of Chinese culture generally.

Evidence that such attitudes are not confined to China can be seen from the following rather jaded comment from a long-time Japan resident who sees a very similar thing going on in Japan, albeit with a strange twist:

Ever since the ‘discovery’ of Japan by the West, Western visitors have gone out of their way to emphasize as many of the unfamiliar aspects of Japanese life as they could, partly because by doing so they made their own stay there sound all the more intrepid … .The most difficult myths to dispel are those concocted by the Japanese themselves: for example, the curious and universally credited myth that Japan is a small country. Of Japan’s four main islands, the largest, Honshu, is slightly larger than all of Great Britain. … Or there is the equally pervasive belief in Japan’s ‘uniqueness’, a quality taken for granted whenever Japanese people attempt to define their country and the ways in which it differs from everyone else’s. For example … ‘The Japanese language is subtle and poetic. Japan is unique. Therefore all other languages are crude and merely “logical”.’ These and similar articles of faith can be encountered at all levels of the social spectrum – in unthinking youths for whom they are reinforced nightly by television quiz shows, as well as in educated ‘opinion makers’ who write books ‘proving’ the Japanese to be totally unlike all other human beings. This class of literature is called nihonjinron (literally ‘Japan People Discussions’), examples of which regularly rank among the nation’s best sellers.

(Booth 1991: 10–11)

Booth comments upon the motivation of Western travellers for emphasising the strange aspects of Japan, something that has also been characteristic of Western travellers’ tales of China since at least Marco Polo, and the fact that this has to do with raising their status in their own culture. This should remind us that such judgments are never made in isolation – there are always cultural, economic or social reasons behind them. What we also see in this extract is that the Japanese, following the lead of the West in this as in so many other areas, have in effect ‘orientalised’ themselves, by claiming a kind of ‘uniqueness’ – again a key term in these kinds of discourses – which they could only have in the eyes of others. This kind of ‘nativised orientalism’ is something we will see in relation to the kinds of discourse about language in the Chinese context in Chapter 6.

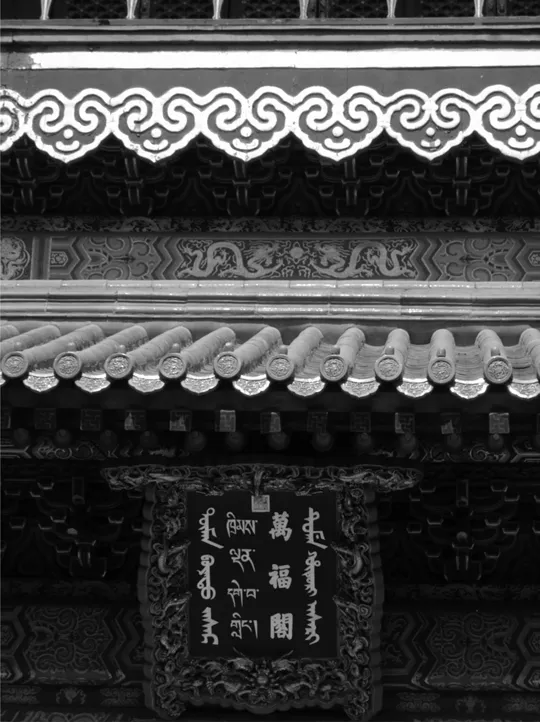

The Foundation Stone of Orientalism: ‘Characters Real’

So from where did these distortions about China in the eyes of Europeans initially derive? And why did the writing system play so prominent a role in them? Some initial answers can be found in one of the earliest formulations of the foundational myth about the Chinese written language, found in the works of English philosopher Francis Bacon. This is the idea which so appealed to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century scholars like Bacon and Leibniz, watching with alarm the decline of Latin as the common language of scholarship in Europe, that Chinese represented a sort of universal language:

[I]t is the use of China, and the kingdoms of the High Levant, to write in characters real, which express neither letters nor words in gross, but things or notions; insomuch as countries and provinces, which understand not one another’s language, can nevertheless read one another’s writings, because the characters are accepted more generally than the languages do extend; and therefore they have a vast multitude of characters, as many, I suppose, as radical words.

(Bacon 1605: 82–83)

This claim contains at least two half-truths, each of which is taken up in different ways by two modern scholars. Philosopher Chad Hansen characterises the written language as follows:

Written Chinese has no alphabet. Each character has a one-syllable pronunciation. The character was viewed as the basic unit of language and was the natural focus of interest for anyone who was literate in ancient China. The characters provided a shared mode of communication among the different Chinese languages since it did not represent any particular pronunciation. Thus, as in China today, people speak different languages but write and read ‘the same.’27

27. Chinese language in archaic times, as at present, differed not only in pronunciation but in grammar and idiom. These differences tended to show up as discernible differences in written style.

(Hansen 1983: 47, 179)

The first half-truth, as expressed by Hansen, is that in traditional China, ‘as in China today, people speak different languages but write and read “the same”’. Even Hansen’s scare quotes around ‘the same’, referring us to an endnote, don’t really soften his claim in any significant way, recognising merely ‘discernible differences in written style’. This seeming concession disguises the raw fact that in modern Chinese, the written language is a register of one particular ‘Chinese language’, that is, Mandarin. A Cantonese speaker, for example, when learning the standard written form is obliged to learn a new language, admittedly one related to his or her own (see Bauer 1988), but with significant differences in vocabulary and grammar, alongside the perhaps more obvious differences in pronunciation concealed by the non-phonemic writing system (on which more below). In imperial China the gap between spoken and written styles was even wider, where the written standard, now known as wényánwén 文言文 or ‘written language’, was based on none of the contemporary spoken languages, but was rather a register based on a group of written texts of the period around 300 BCE (the Chinese ‘Classics’), whose mastery required a long period of education for the elite class who could afford it. The modern written standard, báihuàwén 白話文 or ‘vernacular language’, has also been heavily influenced by this earlier standard in phraseology and to a certain extent in grammar. Thus the advantages of this supposed ‘universal language’, even if its range has shrunk from Bacon’s ‘countries and provinces’ to Hansen’s ‘China today’, would appear to be severely limited ones.

The second half-truth persists in a form perhaps even closer to Bacon’s original formulation of the Chinese written symbols as ‘characters real, which express neither letters nor words in gross, but things or notions’, as shown in the following quotation by literary theorist James Liu:

[A]lthough traditional Chinese etymology postulates ‘six scripts’ (liushu) … two of these concern variant forms and phonetic loans, so that actually there are only four kinds of characters: simple pictograms, simple ideograms, composite ideograms, and composite phonograms. These cha...