- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Narratology

About this book

An Introduction to Narratology is an accessible, practical guide to narratological theory and terminology and its application to literature.

In this book, Monika Fludernik outlines:

- the key concepts of style, metaphor and metonymy, and the history of narrative forms

- narratological approaches to interpretation and the linguistic aspects of texts, including new cognitive developments in the field

- how students can use narratological theory to work with texts, incorporating detailed practical examples

- a glossary of useful narrative terms, and suggestions for further reading.

This textbook offers a comprehensive overview of the key aspects of narratology by a leading practitioner in the field. It demystifies the subject in a way that is accessible to beginners, but also reflects recent theoretical developments and narratology's increasing popularity as a critical tool.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Narrative and narrating

Narrative is everywhere

When we speak about narrative today, we inevitably associate it with the literary type Narrative is of narrative, the novel or the short story. The word narrative, however, is related to the everywhere verb narrate. Narrative is all around us, not just in the novel or in historical writing. Narrative is associated above all with the act of narration and is to be found wherever someone tells us about something: a newsreader on the radio, a teacher at school, a school friend in the playground, a fellow passenger on a train, a newsagent, one’s partner over the evening meal, a television reporter, a newspaper columnist or the narrator in the novel that we enjoy reading before going to bed. We are all narrators in our daily lives, in our conversations with others, and sometimes we are even professional narrators (should we happen to be, say, teachers, press officers or comedians). On occasion, we even take on the role of narrator: for example, when we read bedtime stories to small children. Narrating is therefore a widespread and often unconscious spoken language activity which can be seen to include a number of different text-types (such as journalism or teaching) in addition to what we often think of as the prototypical kind of narrative, namely literary narrative as an art form.

But that is not all. As research is showing increasingly clearly, the human brain is constructed in such a way that it captures many complex relationships in the form of narrative structures (Polkinghorne 1988), metaphors or analogies. Just as we may describe a personal relationship metaphorically as a house that one partner has built painstakingly and lovingly and which the other casually allows to deteriorate until the plaster crumbles and the roof caves in, we may also conceive of each of our lives as a journey constituted by narration. Throughout our lives, things frequently happen without prior warning and bring about radical changes in the course of events, for example the first unexpected meeting with one’s future partner. In reconstructing our own lives as stories, we like to emphasize how particular occurrences have brought about and influenced subsequent events. Life is described as a goal-directed chain of events which, despite numerous obstacles and thanks to certain opportunities, has led to the present state of affairs, and which may yet have further unpredictable turns and unexpected developments in store for us. It is therefore not surprising that psychoanalysis should have incorporated the telling of the patient’s life story into the therapeutic process; indeed, many psychologists give the act of narration a central position in therapy (Linde 1993, Randall 1995).

Narrative and story

The significance of narrative in human culture can be seen from the fact that written Narrative and cultures seek their origins in myths which they then record for posterity. In an explanatory process rather like that of individual autobiographical narratives, historians then begin to inscribe the achievements of their forefathers and the progress of their nation down to the present in the cultural memory in the form of histories or stories. Other areas of culture and society also create their own histories. There is historical linguistics, which ‘narrates’ the development of European languages from proto-Indo-European to present-day Dutch, French, Slovenian or Hindi. And, in the same way, there are music history, literary history and the history of physics. The nation state has its own story. So does current progress in genetic engineering, and the rise and fall of institutions (such as mercantilism or slavery) are also represented in narrative form. Narrative provides us with a fundamental epistemological structure that helps us to make sense of the confusing diversity and multiplicity of events and to produce explanatory patterns for them.

Narratives are based on cause-and-effect relationships that are applied to sequences of events. In historiography, a number of different narrative explanatory models have been applied. From a safe distance one might – to borrow a metaphor from biology – talk about the birth, maturity and demise of a nation. One can also analyse the series of contingencies that have resulted in a particular state of being. One example of this might be the question of why Minnesota has come to have such a strong ethnic German community. (This cannot be described as the inevitable result of a developmental process but is rather related to the chance events of expulsion and resettlement in the age of the Counter-Reformation.) But there are also non-narrative models of historical explanation, such as those which assume that history follows certain natural laws, or those which conceptualize current events as recurrences of crucial moments in a nation’s history: 9/11 as a ‘repetition’ (also in the Freudian or Derridean sense) of Pearl Harbor.

Definition: Whatis narrative?

Having said this, we may well ask: what is not some kind of narrative, or rather, how should narrative be defined in order to distinguish it from non-narrative discourse?

So far we have made use of the term narrative in a way that reflects its popular usage, namely with a multiple meaning. In order to arrive at an explanation for the particular type of narrative involved in a story, we must now turn to the useful distinctions made in narrative theory (also known as narratology), which will clear up at least some of the confusion.

We said above that narrative is derived from ‘narrate’ and that narration is a very widespread activity. Narrative is therefore closely bound up with the speech act of narrating and hence also with the figure of a narrator. Thus one could define everything narrated by a narrator as narrative. But what is it, exactly, that a narrator narrates? Is it a particular novel? Or is it the story that is presented in this novel?

Narrative act – narrative discourse – story

At this point Gérard Genette’s distinction between the three meanings of the French word récit (‘narrative’) provides a way out of our dilemma. Genette draws a distinction between narration (the narrative act of the narrator), discours or récit proper (narrative as text or utterance) and histoire (the story the narrator tells in his/her narrative). The first two levels of narrative can be classed together as the narrative discourse (Fr. discours; Ger. Erzählerbericht) by putting together the narrative act and its product, thus making a binary distinction between them and the third level, the story (Fr. histoire; Ger. Geschichte). The story is then that which the narrative discourse reports, represents or signifies.

Story as fable and plot

These distinctions enable us, for example, to account for the fact that the same story can be presented in various guises. The life story of Charlemagne may be told in a number of ways in different historical works, and the story of Snow White in Grimm’s version is totally different from modern reworkings or parodies of the story’s content. Whereas in the fairy tale the stepmother’s cruelty, with its cannibalistic traits, is foregrounded, and eating in general plays an important role, in modern versions of the Snow White story the excessive cruelties of Grimm’s fairy-tale world are often eliminated, and instead the potentially scandalous role of Snow White in the household of the seven (male) dwarfs gives cause for speculation.1 Thus different narratives focus on quite different aspects of the story; or, more precisely, the stories that we reconstruct from different narrative texts often complement each other. By means of parody or by reflecting current issues and concerns, they fill the gaps that earlier versions of the ‘same story’ (fable) left in their presentation;2 or they simply rewrite the story, for example from a feminist viewpoint. There is, therefore, a level of the story (the fable) that may be taken as the starting point for all Snow White narratives. Moreover, there are numerous textual or narrative manifestations of this fable in the different sequences of events and character constellations, that is to say, in the different plots that constitute the level of the fictional worlds in the many Snow White narratives. The existing texts about Snow White differ from each other quite markedly despite their common core, the fable.

History and storytelling

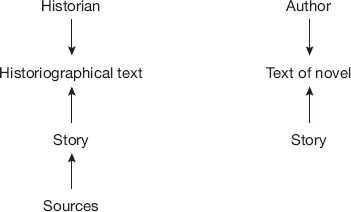

In this respect fictional narrative, whether in fairy tale, novel or television film, differs radically from historical writing. The author of a novel or a film script develops a fictional world and produces both the story and the narrative discourse that goes with its product, the narrative text. Historians, by contrast, construct the most convincing and consistent account of events possible from their sources (which may also be narratives). What is most important here is that they are not allowed to contradict the statements made by their sources without good reason (such as the unreliability of the author of a source text or problems with dating). The historian is not free to invent his/her own story; the only room for speculation is in the areas of indeterminacy between the fixed points provided by historical sources. Despite these restrictions, historical discourses do not tell a single, unambiguous story since each historian has a particular view of things and tends to emphasize certain aspects of the age and the events being described while omitting others.

History always has to do with perspective. No historian or novelist can ever reproduce in toto the (real or fictional) world, otherwise s/he would undergo the same fate as Tristram Shandy in Laurence Sterne’s novel of the same name (1759–67). After several hundred pages of narrative, Tristram has still not managed to describe his birth, since he is so carried away by the minutiae of the prehistory of his conception. But narrative also involves selection. Every history, moreover, can be traced back to a particular perspective. It betrays the view of the author, his/her nationality and place of origin, the age in which s/he writes (or wrote), and it is tailored to a readership which has certain prejudices, historical convictions and expectations. History as historiography is never objective, however great its commitment to telling the truth. History teaching in schools, for example, has traditionally subscribed to the notion of the nation state, one result of which has been an analysis of the state’s relations with other nations in terms of the friend/enemy binary oppositional metaphor. Another consequence of this is that the events of world history have been presented predominantly from ‘our’ (i.e. a European or Western) point of view. Events that were of consequence for the nation state tend to be consistently upgraded and included in the historiographer’s text and plot, while events and developments of central importance abroad are often relegated to the periphery or else left out altogether. History teaching in the West has therefore reflected the enduring Eurocentrism of Western democracies, and in this context the empires of the Chinese, the Moghul dynasty in India or the history of Africa before its colonization by Europe have received scant attention.

Thus far, we have established that fictional narratives create fictional worlds, whereas historians collectively seek to represent one and the same real world in explanatory narrative and from a variety of different perspectives. As readers, we construct the story (characters, setting, events) from the narrative text of a novel, whereas in historical writing it is the historians who produce a story on the basis of their sources and set it down in verbal form. We may represent this as shown in Figure 1.1 below.

Figure 1.1 Story in history and the novel

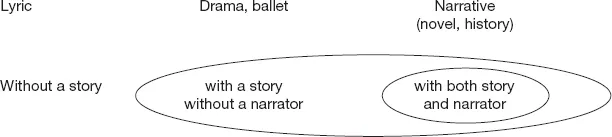

To return to the fairy tale: if one identifies narrative with story (fable), then representations of this story in other media are also narratives. In the English-speaking world it is therefore customary to analyse not only the novel and the film as narrative genres but also drama, cartoons, ballet and pantomime.3 In this sense, the ballet Sleeping Beauty, which presents an underlying story that also exists as a narrative in the form of a fairy tale, could be seen as an alternative manifestation of the same story (fable). The Russian Formalists, who were active in the 1920s and 1930s, coined the useful term fabula (E. fable) for this basic level of narrative. It can also be regarded as the source of a number of versions of the same story, in different media. In what follows I shall therefore make a distinction between the fable (story) and the more particular realization of the subject matter at the level of the plot, that is to say that level of the narrative which is reconstructed by the reader from the discourse as the narrative’s ‘story’. I will refer to this in future as the plot level or fictional world. (The Russian Formalists called it syuzhet, but this term is open to misunderstanding since the term sujet in other languages tends to refer to the thematic level of a narrative.)

The narrator

Let us return to the question of how narrative is to be defined. In German-speaking countries, definitions tend to be rather narrow and relate to the figure of the narrator. This is bound up with the etymologically more closely related German expressions Erzähler (‘narrator’) and Erzählung (‘narration’). Thus, narrative is the story that the narrator tells. German research here continues the tradition of Goethe’s tripartite distinction between epic, lyric and drama whereby the epic is the prototypical narrative category. The epic has a bard, a narrator who tells the story. According to this traditional view there are, therefore, literary genres with an underlying story – drama, for example – but these are not genuinely narrative since they normally do not have a narrator persona as teller of the story.4 Narrative is therefore defined as ‘story plus narrator’, as is represented in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Narrative as defined by the presence of a narrator

In such a conception of narrative, narrative is merely a subset of the genres that include a story.

In the Anglo-Saxon world, on the other hand, as a result of Seymour Chatman’s influential book Story and Discourse (1978), a broader definition of narrative has emerged, which also includes media other than purely verbal (oral or written) narrative discourses. Gerald Prince, in his standard work A Dictionary of Narratology (1987), still defines narrative thus:

Narrative: The recounting […] of one or more real or fictitious EVENTS communicated by one, two, or several (more or less overt) NARRATORS to one, two or several (more or less overt) NARRATEES.

(Prince 2003: 58)

Chatman, on the other hand, defines narrative as a conjunction of discourse and story, but extends the definition of discourse to cover several media. Moreover, by analogy with the narrator in the traditional mould, he introduces the figure of a ‘cinematic narrator’ who is comparable to the narrator in the novel and fulfils a similar mediating function in the presentation of the story. Since the present introduction has been designed for the benefit of students pursuing introductory courses in a range of language and literature departments, I shall concentrate more on the traditional verbal narrative medium and consider film and drama only in certain chapters. Especially in the analysis of plot and action schemas, drama will figure prominently since the analysis of plot in the novel and the treatment of plot in drama are very largely in agreement.

Story and a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- 1 Narrative and narrating

- 2 The theory of narrative

- 3 Text and authorship

- 4 The structure of narrative

- 5 The surface of narrative

- 6 Realism, illusionism and metafiction

- 7 Language, the representation of speech and the stylistics of narrative

- 8 Thoughts, feelings and the unconscious

- 9 Narrative typologies

- 10 Diachronic approaches to narrative

- 11 Practical applications

- 12 Guidelines for budding narratologists

- Glossary of narratological terms

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Subject Index

- Author Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Narratology by Monika Fludernik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.