CHAPTER 1

Introduction: The Mathematical Image

Let’s begin with a nice example, the proof that there are infinitely many prime numbers. If asked for a typical bit of real mathematics, your friendly neighbourhood mathematician is as likely to give this example as any. First, we need to know that some numbers, called ‘composite’, can be divided without remainder or broken into factors (e.g. 6 = 2×3, 561 = 3×11 ×17), while other numbers, called ‘prime’, cannot (e.g. 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, …). Now we can ask: How many primes are there? The answer is at least as old as Euclid and is contained in the following.

Theorem: There are infinitely many prime numbers.

Proof: Suppose, contrary to the theorem, that there is only a finite number of primes. Thus, there will be a largest which we can call p. Now define a number n as 1 plus the product of all the primes:

Is n itself prime or composite? If it is prime then our original supposition is false, since n is larger than the supposed largest prime p. So now let’s consider it composite. This means that it must be divisible (without remainder) by prime numbers. However, none of the primes up to p will divide n (since we would always have remainder 1), so any number which does divide n must be greater than p. This means that there is a prime number greater than p after all. Thus, whether n is prime or composite, our supposition that there is a largest prime number is false. Therefore, the set of prime numbers is infinite.

The proof is elegant and the result profound. Still, it is typical mathematics; so, it’s a good example to reflect upon. In doing so, we will begin to see the elements of the mathematical image, the standard conception of what mathematics is. Let’s begin a list of some commonly accepted aspects. By ‘commonly accepted’ I mean that they would be accepted by most working mathematicians, by most educated people, and probably by most philosophers of mathematics, as well. In listing them as part of the common mathematical image we need not endorse them. Later we may even come to reject some of them—I certainly will. With this caution in mind, let’s begin to outline the standard conception of mathematics.

Certainty The theorem proving the infinitude of primes seems established beyond a doubt. The natural sciences can’t give us anything like this. In spite of its wonderful accomplishments, Newtonian physics has been overturned in favour of quantum mechanics and relativity. And no one today would bet too heavily on the longevity of current theories. Mathematics, by contrast, seems the one and only place where we humans can be absolutely sure we got it right.

Objectivity Whoever first thought of this theorem and its proof made a great discovery. There are other things we might be certain of, but they aren’t discoveries: ‘Bishops move diagonally.’ This is a chess rule; it wasn’t discovered; it was invented. It is certain, but its certainty stems from our resolution to play the game of chess that way. Another way of describing the situation is by saying that our theorem is an objective truth, not a convention. Yet a third way of making the same point is by saying that Martian mathematics is like ours, while their games might be quite different.

Proof is essential With a proof, the result is certain; without it, belief should be suspended. That might be putting it a bit too strongly. Sometimes mathematicians believe mathematical propositions even though they lack a proof. Perhaps we should say that without a proof a mathematical proposition is not justified and should not be used to derive other mathematical propositions. Goldbach’s conjecture is an example. It says that every even number is the sum of two primes. And there is lots of evidence for it, e.g. 4 = 2 + 2, 6 = 3 + 3, 8= 3 + 5, 10 =5 + 5, 12 = 7 + 5, and so on. It’s been checked into the billions without a counter-example. Biologists don’t hesitate to conclude that all ravens are black based on this sort of evidence; but mathematicians (while they might believe that Goldbach’s conjecture is true) won’t call it a theorem and won’t use it to establish other theorems—not without a proof.

Let’s look at a second example, another classic, the Pythagorean theorem. The proof below is modern, not Euclid’s.

Theorem: In any right-angled triangle, the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides.

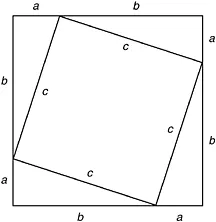

Proof: Consider two square figures, the smaller placed in the larger, making four copies of a right-angled triangle Δabc (Figure 1.1). We want to prove that c2 = a + b2.

The area of the outer square=(a + b)2 = c2 + 4×(area of Δabc) = c2 + 2ab, since the area of each copy of Δabc is From algebra we have (a + b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2. Subtracting 2ab from each, we conclude c2 = a2 + b2. This brings out another feature of the received view of mathematics.

Diagrams There are no illustrations or pictures in the proofs of most theorems. In some there are, but these are merely a psychological aide. The diagram helps us to understand the theorem and to follow the proof—nothing more. The proof of the Pythagorean theorem or any other is the verbal/symbolic argument. Pictures can never play the role of a real proof.

Remember, in saying this I’m not endorsing these elements of the mathematical image, but merely exhibiting them. Some of these I think right, others, including this one about pictures, quite wrong. Readers might like to form their own tentative opinions as we look at these examples.

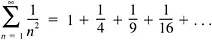

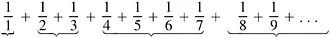

Misleading diagrams Pictures, at best, are mere psychological aids; at worst they mislead us—often badly. Consider the infinite series

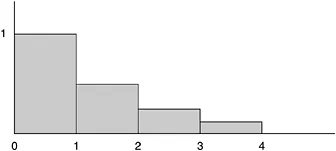

which we can illustrate with a picture (Figure 1.2):

Figure 1.2 Shaded blocks correspond to terms in the series

The sum of this series is π2/6 = 1.6449… In the picture, the sum is equal to the shaded area. Let’s suppose we paint the area and that this takes one can of paint.

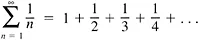

Next consider the so-called harmonic series

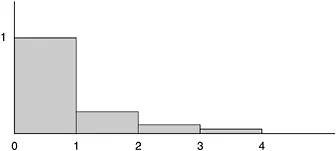

Here’s the corresponding picture (Figure 1.3):

The steps keep getting smaller and smaller, just as in the earlier case, though not quite so fast. How big is the shaded area? Or rather, how much paint will be required to cover the shaded area? Comparing the two pictures, one would be tempted to say that it should require only slightly more—perhaps two or three cans of paint at most. Alas, such a guess couldn’t be further off the mark. In fact, there isn’t enough paint in the entire universe to cover the shaded area—it’s infinite. The proof goes as follows. As we write out the series, we can group the terms:

The size of the first group is obviously 1. In the second group the terms are between and so the size is between and that is, between and 1. In the next grouping of four, all terms are bigger than 1/8, so the sum is again between and 1. The same holds for the next group of 8 terms; it, too, has a sum between and 1. Clearly, there are infinitely many such groupings, each with a sum greater than When we add them all together, the total size is infinite. It would take more paint than the universe contains to cover it all. Yet, the picture doesn’t give us an inkling of this startling result. One of the most famous results of antiquity still amazes; it is the proof of the irrationality of the square root of 2. A rational number is a ratio, a fraction, such as 3/4 or 6937/528, which is composed of whole numbers. √9 = 3 is rational and so is √(9/16) = 3/4; but √2 is not rational as the following theorem shows.

Theorem: The square root of 2 is not a rational number.

Proof: Suppose, contrary to the theorem, that √2 is rational, i.e. suppose that there are integers p and q such that √2 = p/q. Or equivalently, 2 = (p/q)2 = p2/q2. Let us further assume that p/q is in lowest terms. (Note that 3/4 = 9/12 = 21/28, but only the first expression is in lowest terms.)

Rearranging the above expression, we have p2 = 2q2. Thus, p2 is even (because 2 is a factor of the right side). Hence, p is even (since the square of an odd number is odd). So it follows that p = 2r, for some number r. From this we get 2q2 = p2 = (2r)2 = 4r2. Thus, q2 = 2r2, which implies that q2 is even, and hence that q is even.

Now we have the result that both p and q are even, hence both divisible ...