Chapter 1

Mindless photography

John Tagg

The 2005 Durham conference ‘Thinking Photography (Again)’ marked, for me, a return to old ground – to a landscape of my past and to arguments of another time. Yet, in pondering this return, I found I persistently misremembered the publication date of Thinking Photography, pushing it back two years in my mind to 1980 (Burgin 1982). No doubt, this was partly the desire for a neater anniversary as the occasion for retrospect. Even then, I would have had to contest the date since, in its conception and its intellectual style, I have the book firmly in the late 1970s. Such is the reliability of my memory, across so many breaks that would have been all the more liveable if they had only been epistemological.

When I look at the book now, I cannot help but judge it by its cover, in that I find myself held by Victor Burgin’s rather self-consciously contrived, though unattributed, photograph on the dust jacket. I see there the Leica M4, of which Victor was so proud at the time, and a pile of books, certainly brought together for the occasion, yet still pulled from the shelves of his office on Riding House Street perhaps or, more likely, from the bookcases in his apartment on the Albert Bridge Road, opposite Battersea Park. Contrived or not, the cover speaks of a moment when it seemed important and even pressing to bring these books together in this way, as if in themselves they made an important statement: a French collection of essays published by Viktor Shklovski in Russian between 1919 and 1921 (Shklovski 1973); Alan Trachtenberg’s reader, Classic Essays on Photography, from 1980 (Trachtenberg 1980); the fourth issue of Communications, in which Roland Barthes’s ‘Elements of Semiology’ and ‘Rhetoric of the Image’ first appeared (Communications 1964); Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics, though not in the English translation then available (Saussure n.d.); a slim volume on Soviet photography from 1928 to 1932, published in Munich by Hanser in 1975 (Sartorti and Rogge 1975); Walter Benjamin’s Understanding Brecht, which included the translation of his productivist essay, ‘The Author as Producer’, that also appears in the book (Benjamin 1973); then, to one side, issue number 51 of New Left Review, containing the first English rendering of Jacques Lacan’s 1949 paper, ‘The Mirror-Phase as Formative of the Function of the I’ (New Left Review 1968); next to it, volumes four and five of The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, in which Strachey’s translation of The Interpretation of Dreams was published (Freud 1953); and, lastly, opposite and seemingly out of place, the 1978 Aperture edition of Robert Frank’s The Americans (Frank 1978).

It is an odd collection, though you could no doubt trace these same works through the footnotes of the essays that follow, all the way to what now seems the extraordinarily narrow field of reference of the ‘Select Bibliography’, whose purpose, we are told, is ‘to indicate a relatively small number of books and articles in English to which the reader unfamiliar with the general orientations of the foregoing essays may refer’ (Burgin 1982: 217). Today, this little library is both instantly recognizable, as the reading list for an endlessly reiterated pedagogical canon, and yet, at the same time, irretrievably distant, since it is hard now to recall the unwarranted political hopes and eclectic intellectual investments that took these books in hand, waving them as warning, as the red guards once did with the thoughts of Chairman Mao. Here, on this shelf, then, is what was imagined as the space of photographic theory, a space that the introduction is at pains to distinguish from the spaces of ‘criticism’ and ‘history’ (Burgin 1982: 1, 3–4). Wedged between Frank and Freud is the narrow opening in which it was proposed to think photography, to theorize it as a ‘material practice’ – though that is not all there is to say, since there is clearly more at stake on this shelf than merely clearing a space for a discipline. These books are not just stacked up as theoretical tools or as the metonymic figures of a larger project. They are also there as a challenge to all those photographic practices that shirk the work of theory and, as the introduction suggests, do no more than reproduce the requirements of certain fixed repertoires within the vocational divisions of the culture industry that encompass the use of photography (Burgin 1982: 3).

This sense of implicit challenge on the cover, though it hardly lingers now, is a reminder that, at the time it was shaped, the confines of this little space were dreamt within a broader field of activism that was not at all constrained to the academic arena, but that staged itself in what had suddenly become a heterogeneous political field with multiple points of entry demanding inventive forms of engagement. This was the field of ‘cultural politics’ and ‘the politics of representation’ – phrases that evoke a time of uncomfortably brash and abrasive confrontations, of less than subtle polemics and raw counter-practices in which, for a time in Britain in the late 1970s, what was believed possible of theory ran beyond the competition for academic careers. It was a time when the insistent and exhilarating and, no doubt, naïve talk of ‘interventions’ and ‘the politics of culture’ coloured a wider field of action and involvement, changing the sense of possibility, even if the rigour of formulation was not always great and even if the mood was not to survive the forced marketization of the post-Belgrano Thatcher years, let alone the smugness of Major’s Britain or the ‘Socialism with a Lying Face’ ushered in by Prime Minister Blair.

This shelf, then, belongs to another moment, another ‘conjuncture’, in which its strange little theatre of theory was not cast under the proscenium that now defines for us the frame of a discipline. The books on this shelf were put there as a challenge – a challenge echoed in a certain sly insinuation in the overarching title as, in the grammatical shift from participle to adjective, Thinking Photography conjures up not just a bridge between the theorizing of photography and a photography committed to theory, but also this photography’s opposite: a thoughtless photography, an unthinking photography, a mindless photography. This veiled insult, which seemed quite subtle at the time, was certainly intended. In the late 1970s, we knew who the guilty were and could have named names. When, for example, my analysis of ‘Power and Photography’ was first delivered as a lecture, in a series of talks at the ICA in London, just prior to the opening of Three Perspectives on Photography at the Hayward Gallery, it was couched in part as a pointed rebuff to an earlier contributor whom we saw as an arch-proponent of the naïvely untheorized view that truth was to be found by the activist camera out there on the streets. I say this not to revisit such judgements here and now, but rather to mark something of the conjuncture and the discursive field in which as it was put at the time, Thinking Photography made its intervention.

As the handbook of a counter-canon, Thinking Photography self-consciously staked out a site for photographic theory and scrupulously separated itself from what it stigmatized as the myriad forms of mindless practice. Yet, by doing this, it thereby also attached photography to thought, not only as that thought’s possible object, but also as its potential tool, as an extension of the critical mind. This proffered convergence of photography and thought is borne out by the contents of the collection, in which the dominant model for thinking photography is that of language, whether this is framed in terms of a formalized semiotics, as in the contributions by Victor Burgin and Umberto Eco, or in terms of a concept of discursive practice, as in the essays by Alan Sekula and myself. Gone, then, is the conflation of photography with the immediacy and self-evidence of vision. Gone is the camera as analogue of the eye and thereby of the conscious mind and its epistemological relation to the world of experience. Yet, photography still remains a function of mind, as a site of meaning and as the site of inscription of the subject of that meaning: a lucid site, graspable as the landscape of a certain order and recognizable, at least in the imaginary, as a place of belonging, a dwelling of the human that has somehow survived the long trek through the age of Althusser.

I sense we have come to the threshold of a certain limit: the limit, perhaps, of that shelf on the cover. To try to come at what that limit expels, let me hazard two anecdotes – and what could be more anecdotal than a story about the traffic in Central London?

Driving in Central London, of course, is something that has been very much under scrutiny, at least since it became clear in the mayoral campaign of 2000 that part of ‘Red Ken’s’ plan for the inner city was that it should be filled with surveillance cameras. My concern here, however, is not to offer an opinion on the success of Livingstone’s Congestion Charging Scheme in ameliorating the economic and environmental impact of excessive numbers of motor vehicles. Nor is it to speculate on the appetite of administrations of every political stripe for the newest technologies of social regulation. What interests me is the closed circuit of the technological system itself.

The Central London Congestion Charging system was introduced on 17 February 2003 (fig. 1.1). Under its provisions, between 7: 00 a.m. and 6: 30 p.m. on weekdays, cars are charged £8 a day to enter an eight square mile area stretching from Tower Bridge in the east to Hyde Park in the west and bounded to the north and south by the so-called ‘Inner Ring Road’. Drivers pay the charge in advance by telephone, using credit cards, by text message, by logging on to an internet site or at post office petrol stations and retail outlets, and at self-service machines located in car parks. Information on those who have paid is logged into a centralized database, while, on the streets of Central London, almost seven hundred analogue cameras positioned at entry points to the restricted area, at other points within it, and on a number of mobile units, record the number plates of vehicles passing through the narrow field of view of their lenses. The cameras send live video images over secure fibre-optic communications lines to a secret, central ‘hub’ site, operated under contract by private sector service providers. Here, automatic number plate recognition technology identifies and reads each vehicle registration mark in the image stream, compiling an evidential record for use in enforcement actions against drivers who have not paid the charge.

At midnight each day, the ‘hub’ site computers delete the registration numbers of the cars whose owners have paid and relay the plate numbers of those who have not to another computer and thence to the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency in Swansea. This government records centre has databases containing the specifications of all of Bitain’s twenty-eight million vehicles. The data received from the ‘hub’ site is then checked against these records and the names and addresses of defaulters are forwarded to a third centre in Coventry, which issues the penalty notices, doubling the original cost of the congestion charge for payments after 10: 00 p.m. and imposing a £100 fine on those who have not paid by midnight.1 All this takes place through an automated system connected to existing databases and systems of administration, while the use of analogue cameras ensures the conformity of enforcement processes with the evidential requirements of the courts.

It is not, however, the connection of camera to data storage and record retrieval systems that is new. The incorporation of record photography in nineteenth-century policing, medicine, psychiatry, engineering, social welfare and geographical surveys always depended on the deployment of a composite machine – a computer – in which the camera with its inefficient chemical information storage system was hooked up to the file cabinet with its organizational cataloguing system, constituting for the late nineteenth century a new information technology that would radically redirect the public and legislative functions of the archive. What is striking about the London traffic control system is that cameras, records, files and computes are all involved but, except where enforcement proceeds to the courts, there is never a visual presentation.2 This is simply dispensed with as irrelevant. Certainly, part of the circuit involves an imaging process, but the detour via visualization is all but entirely cut out and, whatever process of recognition occurs, it evidently does not involve anything that might be seen as entailing communication, psychic investment, a subject, or even a bodily organ.

Figure 1.1 Cover of London Congestion Charging Technology Trials, Stage 1 Report, prepared by the Traffic and Technology Team within the Congestion Charging Division of Transport for London (February 2005).

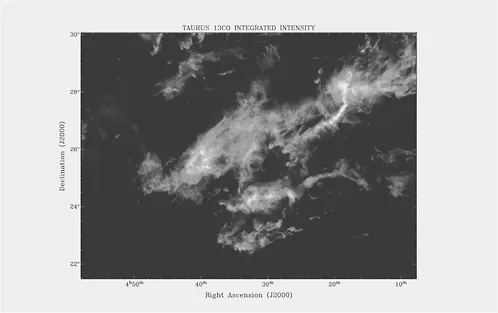

This is interesting and disconcerting. However, let me move to my second instance, which, given my understanding of the science involved, is hardly less anecdotal. It also concerns the surveillance of space, though now of a space of rather larger dimensions than that required to park a car. The lateral space mapped by this image is approximately sixty light years across and the object under scrutiny is estimated to be at a distance of around four hundred and twenty light years from the Earth, which means that the event graphed in June 2005 took place in 1585, or thereabouts (fig. 1.2).

The data on which the image is based were gathered by a radio ‘telescope’ whose parabolic reflector, fourteen metres in diameter, relayed incoming waves into thirty-two feed horns and receiver systems. In order to chart molecular clouds in this part of the constellation Taurus, the reflector as tuned to the frequency of radiation emitted by carbon monoxide molecules, the measurable amount of power coming in at this frequency being proportionate to the amount of carbon monoxide present. The radio telescope used was capable of scanning a square of half a degree on the plane of the sky every two hours. Given this constraint and the limited period in which Taurus was visible above the horizon, it was possible to scan no more than four squares a day, so that this image of three hundred and fifty-seven squares took a little over eighty-nine days of telescope time to complete, not counting time lost to snow, sleet, thunderstorms and equipment failures.3

In principle, the data collected by the radio telescope scans could have been read in digital form by a computer programmed to calculate variations of density and mass. In practice, however, attempts to automate the reading process have met with limited success, not because they have lacked precision, but rather because, at a time when the parameters of the investigation remain open and multivalent, the visual appraisal of morphological variations in the image presentation has allowed for multiple avenues of reading and for the recognition of things that have not been anticipated or built in to the research in advance. Recourse to visualization thus responds to a pragmatics of inquiry that only works, however, when its axes and conventions are strictly defined

For non-specialists, there is ample scope here for misunderstanding. Even as we look at it, we have to remember this is a visual rendering of non-visual phenomena. What the image represents has nothing to do with spatiality, volumetrics or figure–ground relations. It is a record not of light reflected from varied surfaces, but rather of quantity: of intensity of radiation as a measure of molecular density. It is, moreover, an image mapped in two dimensions only, containing no information along the line of sight. It would be profoundly misleading, therefore, to read into it any degree of depth or three-dimensionality. The colour, contrast, brightness and image density, too, are not indexical, but the products of choices framed by the scales of adjustment and arbitrary colour tables written into the software through which the data on radiation was processed. The colour and tonal contrasts thus have no meaning, except in relation to the heuristic graphic conventions that calibrate signal strength in terms of preset colour variations. Historically, indeed, it was only the development of digital graphic software programs that enabled coloured image displays such as this to replace earlier astronomical maps that charted variations in density recorded by radio telescope data with ‘contour lines’ that were often hand drawn. In short, then, this is neither a photograph nor a visual equivalent, however much we might want to see here an apotheosis of Stieglitz or some cosmic drama on a truly Baroque scale, as if we were witnessing Tintoretto’s Origin of the Milky Way stripped of its allegorical figures and exposed in the awesome, luminous vastness of its primal space.

Figure 1.2 Taurus 13CO 7 June 2005. Radio telescope image of solar dust cloud radiation from the Taurus Molecular Cloud Survey, National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center, Cornell University, 2005. Courtesy of Paul Goldsmith, formerly James A. Weeks Professor of Physical Sciences at Cornell University, now at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

What we have instead is an artefact whose value is embedded in the ‘complex and sophisticated system of visual hermeneutics’ in which, through instrumentation, targeted phenomena are prepared and produced as visually readable (Ihde 1998: 77).4 Driven by what Don Ihde has termed the ‘engineering paradigm’ of ‘scientific visualism’ (1998: 159), proliferating technologies now routinely convert even non-visual sources into visual ones through such processes as X-rays, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission scans and computer assisted tomography. Astronomy, indeed, was one of the first sciences to set off down this path, using technologies developed in the Second World War, such as radar and low noise radio receivers, to move from optical instruments, restricted to things observed in visible light, to radio astronomy and, more recently, to the exploration of spectra far beyond the wavelength range to which human eyes are sensitive. With such new instrumentation previously unknown phenomena, such as pulsars, quasars, cosmic background radiation and the interstellar dust and dense gas clouds from which new stars are formed, have been constituted as visually graphable images, most often – as here – through conventions of fictive colouration.

In contrast to Ihde, however, I am not here concerned with the epistemological claims made in a technico-scientific hemeneutics for visualization and the necessary distance it implies. It is not the truth-value of the image that engages me, or the protocols of multi-instrumental repetition and variation through which this truth-value is institutionally secured, at least within a certain community of discourse. No more is it a matter of the processes of technological enhancement whose results are both more and less than the sensor...