- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Occupational stress affects millions of people every year and is not only costly to the individual – in terms of their mental and physical health – but also results in major costs for organisations due to workplace absence and loss of productivity. This Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) based self-help guide will equip the user with the necessary tools and techniques to manage work related stress more effectively.

Divided into three parts, this book will help you to:

- understand occupational stress

- learn about a range of methods to reduce stress levels

- develop your own self-help plan.

Overcoming Your Workplace Stress is written in a straightforward, easy-to-follow style, allowing the reader to develop the necessary skills to become their own therapist.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Understanding occupational stress

Chapter 1

Occupational stress and its consequences

In order that people may be happy in their work, these three things are needed: They must be fit for it. They must not do too much of it. And they must have a sense of success in it.

(John Ruskin 1819–1900)

Normal stress

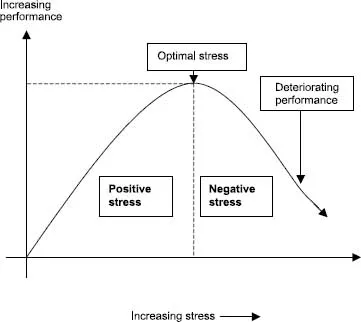

When reading the literature about stress it would be easy to conclude that it has universally negative consequences and that it is something that needs to be eradicated from all areas of our lives. However, it is important to emphasize from the outset of this book that not all stress is bad for us. A certain degree of stress is a natural, normal and unavoidable part of everyday life. For example, most of us can relate to the stress we have experienced when we have been about to take an exam, do our driving test, or give a presentation to managers or colleagues at work. This is known as positive stress, because it motivates us to do well and can actually enhance our performance on the task in hand. With positive stress the individual is motivated to meet the challenge and ultimately experiences a sense of achievement at having successfully mastered it (as acknowledged in the quote by John Ruskin above). This normal type of stress does not have any lasting consequences and if successfully managed, it can result in an increased sense of competence, fulfilment and wellbeing. There is an evolutionary explanation for this kind of stress in that our ancestors’ reactions to perceived threats and dangers had survival value. For example, in primitive society, hunter-gatherers would on occasions risk their lives in the hunt for food or to defend their community. In doing so, they would experience dangers which would have triggered the body’s stress response. This in turn would have prepared the individual for action, either to fight or to escape the threat. In modern societies and cultures, however, the stressors experienced are not usually life threatening in the way that they were for our ancestors, but they still trigger the stress response. The relationship between stress and performance is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The stress–performance curve.

It can be seen on the left hand side of the graph in Figure 1.1 that low to moderate levels of stress actually serve to enhance performance until the optimal level is reached. However, once the level of stress exceeds the optimal level, there is a rather rapid and steep decline in performance and it is this that is described as negative stress.

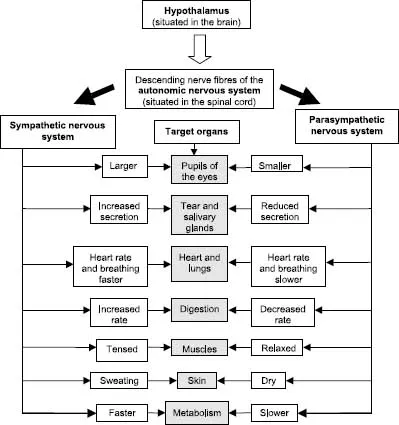

The ‘fight or flight’ response

While it is not necessary for the purposes of this book to know the detailed anatomy of the brain, it is useful to know a little bit about the biological and chemical basis of what is known as the ‘fight or flight’ response to stress. Of particular relevance to discussion of the fight or flight response is the autonomic nervous system. This extends from the brain to most of the important organs of the body and consists of two parts, called the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Also within the brain is a structure called the hypothalamus, which has two distinct segments that are linked to the autonomic nervous system (see Figure 1.2). One segment is concerned with bodily arousal and is linked to the sympathetic part and the other segment is concerned with the reduction of bodily arousal and is linked to the parasympathetic part of the autonomic nervous system. The hypothalamus thus forms the starting point of the two sections of the autonomic nervous system. The physical consequences of the activation of the two respective parts of the autonomic nervous system on the organs of the body are shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Diagrammatic representation of the structure and function of the autonomic nervous system.

The pituitary gland is a structure linked to the hypothalamus by a small stalk and connected to it by both nerves and blood vessels. It is the ‘master gland’ of the body and produces a number of hormones which control the activity of other glands elsewhere in the body. The most important of these glands in relation to stress are the adrenal glands, which are situated in the kidneys and assist the body to cope with stress by producing hormones. When the brain interprets a situation as being stressful, it triggers the pituitary gland to produce chemical messengers which instruct the kidneys to release stress hormones called epinephrine and norepinephrine into the bloodstream. These stress hormones are pumped around the body and result in the fight–flight response.

Harmful stress

Under conditions of successful coping, the parasympathetic nervous system is suppressed. However, if the individual is not successful in overcoming the threat and the stress reaction continues without successful resolution for a prolonged period of time, the individual moves into a chronic phase. Examples of such chronic stressors include things like being stuck in a bad marriage, living in noisy or overcrowded conditions, and career or work related problems. In the chronic phase the parasympathetic nervous system becomes overactivated, bodily systems are inhibited and there is decreased physiological arousal, as shown in Figure 1.2. This is achieved through the release by the kidneys of a different stress hormone called cortisol (which is also associated with depression). If the stress continues, the individual eventually becomes physically exhausted and ultimately can become depressed.

The model of stress described here is thus a two stage one characterized by acute and chronic phases. If the individual experiences high levels of stress (acute stress) for a short period of time, it is unlikely to do any lasting harm, but if it continues over a prolonged period of time (chronic stress), it not only has detrimental effects on their performance but also can have harmful longer-term physical and mental consequences. Some of the harmful physical and mental consequences of chronic, long-term, unmitigated stress for both the individual and the organization are reported below.

The consequences of harmful stress on the individual

Prolonged moderate levels of stress can lead to physical ailments such as headaches, backache, poor sleep, increased heart rate, raised blood pressure, dry mouth and throat, and indigestion. The individual may also experience a range of physical symptoms associated with anxiety, such as muscular pains, tremors, palpitations, diarrhoea, sweating, respiratory distress and feelings of dizziness. On an emotional level it can lead to feelings of anger and irritability, low mood and depression. Socially the individual may experience increased levels of marital and family conflicts, reflecting the stresses of the work situation that they take home with them. People under stress also tend to withdraw from supportive relationships; in the longer term this can lead to marital breakdown and social isolation. Mentally the individual may experience difficulties concentrating and remembering things, or may be prone to more negative thinking leading to increased feelings of self-blame and reduced feelings of self-confidence. Behavioural consequences of stress can include increased alcohol intake, increased smoking and drug use, overeating or loss of appetite, and less of an interest in sex. In the work context the individual may experience increased arguments and interpersonal conflicts, be less productive and more prone to accidents.

Prolonged high levels of unmitigated stress can lead to more serious physical health problems developing. For example, it has been found that digestive disorders and diabetes often follow prolonged high levels of stress. High and prolonged levels of stress can also compromise the effectiveness of the body’s immune defences, making the immune system less effective. This allows diseases and infections which would normally be fought off by the immune system to take hold. Links have also been found between stress and coronary heart disease.

The consequences of harmful stress for the organization

‘Occupational stress’ is the term used to describe the stress experienced as a result of the job that one does. It is the common cold of the psychological world and has become a problem of pandemic proportions, affecting millions of people in every country across the world. This is due to the ever increasing pressures being placed on workplace organizations to adapt and change in order to become more efficient in the context of a highly competitive global economy. It is estimated that up to 40 per cent of all sickness absence from work is due to stress related symptoms, and this is costing employers and health insurance companies billions of pounds each year in lost productivity and health insurance claims. But the costs of occupational stress to employers are much broader than just those incurred through sickness absence. They include increased staff turnover, recruitment problems, low staff morale, decreased productivity, poor timekeeping, impaired decision making, increased industrial conflicts, increased accident rates, premature retirement due to ill health, redeployment, retraining, replacement costs, grievance procedures and litigation costs.

It is estimated that we spend on average at least one hundred thousand hours of our lives at work, so it is crucial that we find it a satisfying and rewarding place to be. Given the fact that we spend so much of our time at work and the serious consequences of chronic unmitigated stress, one might argue that if we are experiencing stress, we should remove ourselves from it. For example, we should leave a bad marriage, move out of poor living conditions or find another job. So why not just avoid the stress in the first place? The answer is that in reality it is often not that easy to simply walk away from the stress we are experiencing. With respect to leaving a marriage, there might be children involved, or with poor living conditions we may not be able to afford to pay for anything better. Similarly with employment there may be numerous reasons why we are unable to simply walk away from the job. We are thus left to find alternative ways to manage the stress we are experiencing.

Conceptualizing stress

Over the years numerous definitions and conceptualizations of stress have been cited in the literature. Some have taken the view that stress is caused solely by events or characteristics in the environment. Others have defined stress in terms of the response of the individual to the demands of their environment. However, these definitions cannot explain why it is that two individuals confronted by exactly the same situation can react very differently to it and consequently experience different levels of stress. Cognitive therapists argue that in many situations it is not the environment itself that causes stress but the individual’s appraisal of the situation or event in their environment. It is of course not the intention here to imply that individuals are responsible for causing all of their own stress but simply to emphasize the importance of the meaning that we attach to situations as a factor which mediates between the environment and the level of stress experienced. Nor is it to deny that there are some environmental situations that may be objectively stressful for anyone.

In the work context, the saying ‘one man’s meat is another man’s poison’ summarizes this approach well, since two employees doing exactly the same job can, according to the model, appraise and experience the job in very different ways. One employee can appraise the job as being stressful whereas another employee can appraise it as being challenging and satisfying. There is a growing consensus among psychologists that stress is the result of an interaction (or transaction) between an individual’s appraisal of their environment (i.e., the meaning that they attach to it) and the actual environment itself. This is known as the transactional model of stress.

The ‘camera analogy’

Aaron T. Beck, who is considered by many to be the father of cognitive therapy, used a camera analogy to describe the interaction of the individual with their environment. He likened an individual’s construction of a particular situation or event to taking a snapshot. When taking a photograph of a particular event or situation, the existing settings of the camera (e.g., lens, focus, speed and aperture settings) all determine what the eventual picture obtained will look like. For example, there may be some blurring or loss of detail due to inadequate focusing, or some distortion or magnification of the picture if a wide-angle or telephoto lens has been used. Likewise, a photograph taken with a soft focus sepia finish will convey a different message from a sharp focus black and white picture. In a similar way, Beck argued, the pre-existing ‘cognitive settings’ of an individual’s mind will influence the way an event or situation in their environment is perceived. He called these pre-existing cognitive settings ‘schemas’.

Schemas are stable structures that process incoming information to the brain in a similar way as the lens, focus, speed and aperture settings described in the camera analogy. They are formed by early life experiences and determine that individual’s propensity to interpret situations in a particular way. For example, if the individual has experienced significant rejection in their childhood, they will be particularly sensitive to situations or events that signal rejection. Thus, a situation signalling rejection will result in activation of that schema and the individual will experience it as stressful. However, an individual who does not have the rejection schema will not interpret the situation as being stressful. Once the unhealthy schema is activated, the individual begins to feel and behave ‘as if’ they were in reality being rejected. Thus, schemas are at the core of stress reactions, because they provide the meaning of an event for the individual. If through the activation of their schemas an individual perceives that a threat is present, and the risk posed by t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Understanding occupational stress

- Interventions for occupational stress

- Pulling it all together

- Appendix Useful books and contacts

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Overcoming Your Workplace Stress by Martin R. Bamber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.