1

Bringing the Chinese Communist Party back in

On 11 September 2007, prior to the Seventeenth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (15–21 October 2007), Li Rui, who used to be Mao Zedong’s political secretary, published an open letter to General Secretary Hu Jintao entitled ‘Some Suggestions on the Reform of the CCP’.1 In his letter, Li presented a set of arguments on why the reform of the CCP itself should become a top priority for the Party leadership. The arguments were organized around the theme of democracy and sophisticatedly presented.

Li first quoted some strong arguments for democracy made by Chen Duxiu, one of the founders of the CCP. Chen had played an important role in the May Fourth movement in 1919. In 1942, prior to his death, Chen criticized Joseph Stalin’s personal dictatorship in the Soviet Union and argued for democracy. According to Chen:

Li went on to elaborate how and why the personal dictatorship under Mao Zedong led to endless political disasters in China such as the Anti-Rightist movement (1957–58), the Great Leap Forward (1958–60) and the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). Li argued that to prevent such disasters from recurring, the CCP has to engage in political reforms. Moreover, the reform of the CCP itself is the key to the success or failure of all other reforms in China today, and is also the central theme of China’s political reforms. Then, how to engage in Party reform? Li informed that when he was invited to a conference at Harvard University in 1989, Western scholars had then referred to China as a Party-state (dangguo). So, he argued that the goal of Party reform is constitutionalism, where the Party should subject itself to the state, but not the other way around. Li suggested (as he did prior to the Sixteenth Party Congress in 2002) that the National People’s Congress should make the Law on Political Parties (zhengdang fa), which would provide legal constraints on the behaviour of the CCP.

Li is not a lone figure within China arguing for Party reform. In recent years, more and more people like Li have begun to call for Party reform. Prior to the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March 2007, Xie Tao, a former vice president of the People’s University of China, published an article entitled ‘Only Democratic Socialism Can Save China’ in a liberal journal called Yanhuang Chunqiu, which is widely circulated among Chinese liberals both within and without the CCP.3 In his paper, Xie also presented a similar set of arguments for Party reform. Xie said, ‘Sun Zhongshan [Dr Sun Yat-sen] established the Republic of China. The Constitution was written, and the parliament was founded. But Chiang Kai-shek emphasized one-party rule, and one-leader rule. The party [Kuomintang, KMT] was above the constitution and above the parliament, and leaders were above the party, and the dictatorship continued.’4

Xie told a story: When Zhang Youyu, who introduced Xie to join the CCP, was dying, he said to Xie, ‘After the Victory of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937–45), we witnessed the Kuomintang’s dictatorship and corruption, and how it eventually lost people’s hearts and lost its power. We, old comrades of the revolution, can no longer witness that our Party [CCP] will also follow the path of the KMT.’ Xie argued that constitutionalism is the only way for the CCP not to repeat what the KMT has done before. According to Xie, the Party leadership should give up traditional Marxism and communism and follow the European model of socialism, namely, democratic socialism. He argued that only democratic socialism can save China.5

Both Li and Xie used to occupy important positions within the CCP, and they both live in China. They express their opinions when they feel that their opinions can generate political influence, meaning that their opinions will be amenable to liberals within the Party and in Chinese society. As expected, they would have predicted strong reactions from Party conservatives and the so-called leftists in society.

Despite all the controversies around Li’s and Xie’s arguments, both liberals and conservatives within the CCP generally agree that the reform of the CCP is an urgent agenda for the Party leadership. What they disagree on is what direction the reform should take. Over the years, the CCP has fast lost its identity, not only among its own members but also in social groups. In his political report to the Seventeenth Party Congress, Hu Jintao recognized that, ‘In-depth investigations and studies have yet to be conducted on some major practical issues related to reform, development and stability.’6 Needless to say, the erosion of the Party identity is a pertinent issue. Hu argued:

The above discussion serves multiple purposes. Both Li and Xie raised at least two important questions about the CCP. First, what is the CCP? This obvious question does not imply an obvious answer. As indicated in Hu Jintao’s report to the Seventeenth Party Congress, the question of what kind of CCP China should build, and how to build it, remains open. There is an issue of Party identity. How does the Party identify itself? How do social groups in China identify with the Party? These are unanswered questions with political significance. When Li expressed his unhappiness about China’s Party-state and insisted that a law on political parties should be made, he believed that the Party should be a part of state institutions. In other words, the CCP is so far not a part of state institutions, but above all state institutions. Second, what direction is the CCP heading in? Recent controversies among different social groups (e.g., liberals and new Leftists) about the CCP are due to the fact that the CCP is undergoing transformation. Despite its authoritarian structure, the Party has changed quite drastically since the reform and open-door policy. Given the fact that the Party is the only ruling political body in China, any major changes to the Party will affect the redistribution of political power among different political and social groups. Some groups will benefit more than others. Still, other groups might become victims of such changes. Understandably, different groups will present their own ideal world of the CCP. Xie’s democratic socialism model for the Party falls under this mould.

Furthermore, these two questions are also meaningful for academic communities. As will be discussed later, scholarly studies of the CCP have been sidelined in recent decades. Now with Party reform becoming an increasingly important agenda in China, it is time to bring the CCP back in. Therefore, the above discussion also aims to remind the scholarly community how unprepared we are to answer such important questions.

The purpose of this study is to answer these two key questions about the CCP. To answer the first question – What is the CCP? – this study will take an approach suggested by Emile Durkheim to study ‘social facts as things’.8 It will attempt to develop a cultural theory to explain the CCP as a thing and a social fact. To answer the second question, this study will examine how the CCP has behaved, and why it has behaved this way. It will not answer what direction the CCP should follow. In other words, the question will be answered in a positive sense, not in a normative sense.

In the following sections of this chapter, I first discuss why the CCP continues to matter, and then examine how relevant existing literature on political parties is to the CCP. While explaining why scholarly studies of the CCP have been sidelined, the discussion also provides an intellectual background for the next chapter where an analytical frame for a cultural interpretation of the CCP will be set up.

The CCP matters

In today’s world, no other political organization is able to wield as huge an internal and external influence as the CCP. The CCP is the largest political party in the world. As of 2008, its membership totalled 73 million, larger than the total population of France (the second most populous country in the European Union with 64 million people) and Iran (71 million). The CCP is also governing China’s population of more than 1.3 billion, the largest country in the world.

Since the late Deng Xiaoping initiated the reform and open-door policy in the late 1970s, China has achieved unprecedented economic performance at an annual growth rate of nearly 10 per cent. China has become the fourth largest economy in the world, after the USA, Japan and Germany in terms of total gross domestic product (GDP). Furthermore, China’s economy is export-oriented and is highly integrated into the world system. Whatever happens inside China will generate profound external impacts. The CCP, as the only ruling party in China, has played an important role in initiating all major reforms in the past three decades. By extension, it is also the only political actor responsible for dealing with the consequences resulting from rapid socio-economic transformation.

Founded in 1921 in Shanghai, the CCP has gone through dramatic transformations in the past century. From a party of merely 53 members in 1921, the CCP survived the political onslaughts of the KMT in the 1920s and 1930s and expanded drastically in subsequent decades. Under the revolutionary leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP became the ruling party of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. The CCP also survived Mao’s ‘continuous revolution’ after 1949, including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. After Deng Xiaoping took over power, the CCP embarked on an unprecedented socio-economic transformation of China.

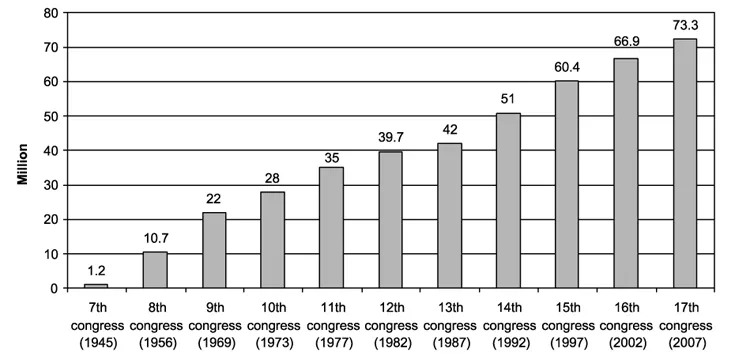

In the past three decades, the CCP itself has experienced even more drastic changes. The Party recruited 12 million new members at an annual rate of 2.4 million (see Figure 1.1). By the end of 2006, the CCP had 3.6 million organizations, including both Party committees and Party branches at the grassroots level. More than 420,000 firms had established Party organizations. Out of 2.4 million firms in the non-state sector, 178,000 (7.4 per cent) had established Party organizations.9 In other words, Party organizations have penetrated into all forms of firms, institutions, and social organizations.

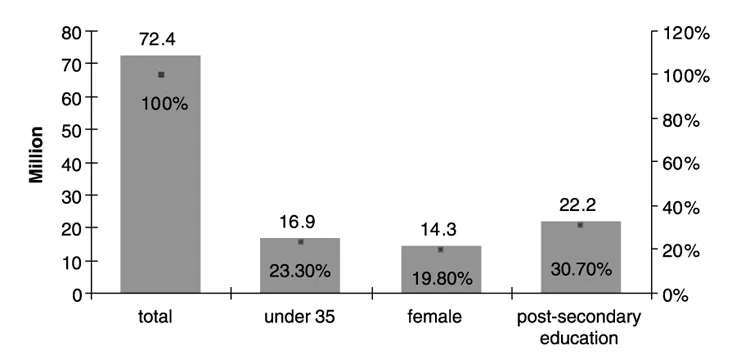

While the CCP remains a highly authoritarian structure, the composition

of its membership has changed (see Figure 1.2). The newly recruited members are usually younger and better educated. By the end of 2006, the number of Party members under 35 stood at 16.9 million, comprising 23.3 per cent of the total membership; Party members with a post-secondary education or above amounted to 22.2 million, about 30.7 per cent of the total; female Party members numbered 14.3 million, about 19.8 per cent of the total.10

At the policy level, the CCP is increasingly becoming important not only for China itself but also for the world. With its rapid economic rise, China has become an important player in world politics. However, the international community feels uncertain about China, both in terms of the sustainability and the direction of its development. Among the sources of uncertainties

about China, the most important is undoubtedly the CCP. Communist parties in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe did not survive the twin challenges of economic reforms and political democratization there. Given that socio-economic changes in China are more drastic in many ways than these former communist states, will the CCP continue to survive its ongoing transformation? It is a legitimate question for the scholarly community. Once deemed the vanguard of the Chinese State, the CCP’s declining ideological appeal, its equally unattractive and clumsy structure, and its disillusioned Party cadres are increasingly making the Party’s sustainability problematic. China’s ‘open-door’ policy and the rapid globalization process in the post-Cold War era have generated increasingly high pressure for changes in the leadership of the CCP. Party reform appears to be most logical and urgent, and indeed the CCP leadership has engaged in various forms of Party reform to sustain its rule.

While the CCP continues to matter, it has also posed various forms of intellectual puzzles for the scholarly community. There is hardly any consensus on the CCP and its future. Scholars are highly divided in interpreting the direction of the CCP’s evolution and the nature of the Party. At one extreme, optimists tend to believe that China’s current ossified Leninist Party-state will eventually succumb to the inevitable march of democracy. On the other extreme, some pessimists believe that China’s transition has been trapped while others predict the inevitable fall of the communist system. Both camps of scholars seem to have obtained substantial evidence to support their arguments, often leaving the reader wondering which camp is more credible and raising uncertainty about the future of the CCP.

For years, China scholars have been concerned about the sustainability of the CCP. Since the crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in 1989, many scholars have frequently predicted the fall of the Chinese communist regime. Immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern European communism, Roderick MacFarquhar claimed that it was only a matter of time before China went the same way as these regimes.11 It seems that more radical reforms and greater openness triggered by the late Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992 did not lead scholars to change such a deeply rooted mindset. In 1994, Avery Goldstein stated that, ‘[a]lthough scholars continue to disagree about the probable life-span of the current regime, the disagreement now is usually about when, not whether, fundamental political change will occur and what it will look like’.12

In recent years, more scholars tend to believe in the coming collapse of communist rule in China although the country has sustained three decades of reforms. The issue of the sustainability of the CCP was raised in a recent debate on ‘Reframing China Policy’, organized by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based think tank.13 In the debate, two leading China experts in t...