Chapter 1

On Wonder

Some time ago Jesse, a kindergarten child, and I were scurrying through a heavy rain on the way from my car to his classroom. I remarked that it had been raining pretty heavily for some time and over a large area. That was a lot of water and it must be very heavy. Had he ever lifted a bucket of water? Yes, he had, and it was really heavy. So what did he think about how all this water could stay up in the sky? By this time we had entered the building and he looked at me and proceeded to explain that there was a great big glass or plastic ceiling in the sky. Moreover, that’s what thunder was—when it would crack. This was a wonderful theory, and I said so; but it occurred to me that he had recently flown for the first time. Did he think the plane had broken through the glass barrier? He didn’t say anything at first … you could see him thinking about things, and of course the most striking feature of flying is looking down on the clouds. Then he said that he hadn’t thought of that. Maybe his idea wasn’t right. Maybe something else held the water up. “Wonder what it is,” he said. “Yes,” I agreed, “wonder what it is.”

When Jesse had paused before he went off to join his kindergarten class, when he paused to say “Wonder what it is,” the wonder he expressed was not so much a wonder of nature as a wonder of the human imagination. It was not the rain he was wondering about, but the intricacy in thinking through how it might work. This is an important distinction. Often people take science to be about nature’s wonders, but it isn’t. Science is not a series of National Geographic specials on volcanoes or the fantastic world within a microscope or the birth of stars. It’s how we understand these things.

Of course, in seeking to understand nature we need some experience, but too often science class becomes a time to marvel at the world when it ought to be a time to marvel at reason and the power of the imagination.

There’s a lovely story about the connection between reason and the imagination that comes from the latter years of the eighteenth century and seems exactly right here. James Hutton, a Scottish man of science, had proposed that we link the hard, crystalline rocks so abundant in the Earth’s crust, rocks like granite and marble, to volcanoes and fires deep within the Earth. This was a remarkable hypothesis. The only rocks clearly derived from volcanoes are rocks like pumice, rocks that are porous and brittle with a dull, matte-like finish—utterly different from the granites and marbles Hutton proposed also came from volcanoes.

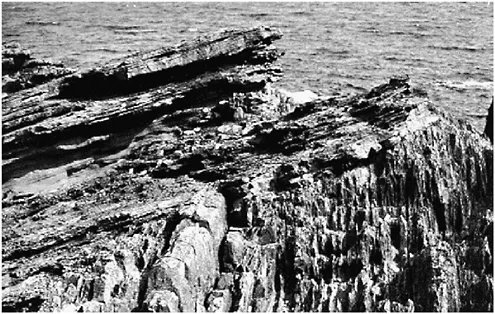

Hutton ably made his case and deeply transformed the way we understood the Earth’s history. Before Hutton, the story of the Earth was the modest tale of a gradual wearing down, as the wind and elements eroded its bolder features. With Hutton, things opened up dramatically. Different parts of the Earth could be different ages, depending on the play of igneous forces. Whole mountain ranges and continents could be relatively old or young. The Rockies, for example, are only about 40 million years old; while the Appalachians are around 300 million years old. Moreover, in a given place the layers of rock may reveal a history of the rise and fall of landscapes as complicated as the rise and fall of the kings and queens of medieval Europe. This was immediately clear to Hutton and his colleagues on a trip into the field when they came to Siccar Point, which juts out into the North Sea some 30 miles east of Edinburgh. There they found two beds of sedimentary rock, each one representing a long stretch of time when this region had been below sea-level so that sediment could accumulate and compact into rock. Furthermore, the fact that the lower, older bed was vertically standing meant that it had been upended from its original horizontal lie by powerful forces long before the younger bed had been formed above. Here is a lovely photo of Siccar Point from the geology department of Lawrence University in Wisconsin.

Reconstructing the likely sequence of events that had produced this vista— two separate events of uplift and vast spans of time for erosion and the accumulation of sedimentary rock—John Playfair, one of the group wrote: “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time, … ” and then he added “we became sensible how much farther reason may sometimes go than imagination can venture to follow” (Playfair, 1822, vol. 4, p. 81). When we marvel at the intricacies of the world of electron-microscopy or at the vastness of distant nebulae “dying in a corner of the sky,” we are carried to these fantastic worlds, not by the imagination of the poet, but by the careful reasoning of the scientist making sense of the world.

“Excuse me, but don’t you have that upside down? Everyone knows that poets are imaginative and carry you to exotic places like Xanadu; while careful reasoning only gives you whatever fantasy you can find in the fine print of a footnote.”

“Oh, hello. I know what you are talking about, but if you stop to consider the proportions of modern science from black holes to the ‘charm’ of quarks, isn’t it clear that reason sometimes goes far beyond footnotes or Xanadu?”

“You make science out to be a something like the Twilight Zone. But isn’t it all about the facts? What about careful observation and the scientific method, meter sticks and triple-beam balances?”

“Facts and observation are there, but they’re a small part of things. There are always two stories to tell. There’s the one that features the thing itself. You know, the ‘Wonders of Nature’—from the intricate lace-like patterns of snowflakes to the dramatic images of nebulae billions of light years away. These are the stories we find on public television specials. They’re great, but there is another kind of story. It’s the one we invent in order to understand. It’s the one with all those wonderful notions about things we can’t even see—such as atoms, the double spiral of the DNA molecule, evolution …”

“Whoa! Do you mean atoms and evolution were just made up?”

“Certainly! Evolution is far too slow to see, and atoms are far too small for us to experience. You can’t pick one up, hold it to the light to see what color it is, or place it on a scale to weigh it. The atom was invented, not discovered. The key here is a matter of how we see things. Let me tell you a story …

“Some time ago I went hunting for dinosaurs. As I went, I remembered the Golden Book of Big Dinosaurs I’d read as a kid: their monstrous size, the violence of their eyes, their fierce step, and their great jaws. It was a completely foreign and exotic world. Yet, it was also a real world. Perhaps this is the key to their mystique; here were dragons that actually stomped about and breathed their fiery breaths. That’s why you get all those marvelous tales, such as Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park (1990), where hidden away in lost corners of the globe are descendants of the lumbering beasts of the Mesozoic. We are captivated by the thought that they were real.

“On my expedition, we went back to the mid-Jurassic, to the Morrison formation—rocks of a characteristic type deposited 150 million years ago but presently found all around you, if you happen to be in parts of Colorado and elsewhere. We can all conjure up the lost world of the dinosaur. A typical scene might involve great beasts lumbering through swamps, or locked in deadly combat, and of course, there are volcanoes smoldering in the background (this is the cover illustration by Joel Snyder of David Eastman’s Now I Know: Story of Dinosaurs, 1982).

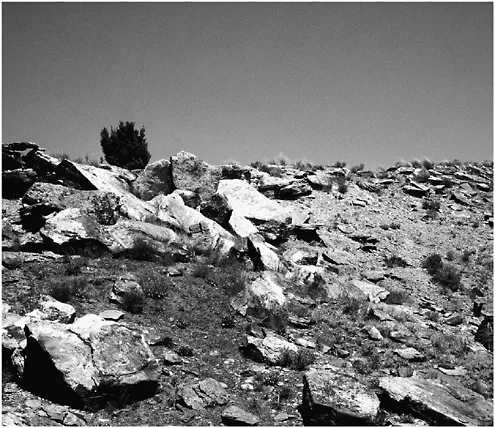

“What an extraordinary contrast this is with the modern scene, the one that shows a barren and bleak hillside, no volcanoes, no swamps. We had gone to

a site near Grand Junction, Colorado, in the Western range of the Rocky Mountains, not very far from the Utah border, a most prosaic patch of arid land.

“If you could superimpose these two scenes, you would have the measure of the difference between facts and theories. Here we are, reason tells us, knee-deep in the world of the Iguanodon and the Apatosaurus, with Pterodactyls in the skies, flanked by Tyrannosaurus Rex in battle with a Triceratops, the great plebeian warrior. Giant ferns grow around us, while volcanoes are smoldering, and what do we see? What are the facts? A bleak, bleached out hillside!

“At a certain point in our scouring of the hillside, I realized that everyone else had found a fossilized morsel to relish, and that all I had been able to do is swat at the predatory gnats that are a large part of the modern environment. Determined not to let the moment escape, I opted for the beaten path and began to search for some sign of ancient life in the rocks just a few feet to the right of another find.

“I clambered along the slope, chose my spot a respectful distance away, and began to scrape at the surface. Success! I found two small lumps of dark rock! I called out to my friend, a paleontologist, and he came over right away. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘a great find. It looks like two vertebrae of a Camarasaurus.’ I had done On Wonder 5 it! I had found the remains of a dinosaur. The Camarasaurus was a beast of that broad, sleek Apatosaurus design, though quite a bit smaller. Its remains are not uncommon in the Morrison, and there are some lovely specimens on display at Dinosaur National Monument not too far away in Vernal, Utah.

“Then, right at the height of my joy over my great discovery I learned we had to go. I was shattered. One of our party was, unfortunately, quite ill, and ought not to have gone out in the first place. And so everyone packed up their goods and made for the car and the ride back to town. I was left standing there in a daze, staring at my two lumps of dark rock; since that was all they were. I wasn’t going to have the chance to bring them to life. The reality they constituted would continue to be a private affair between them and their setting. I hadn’t found vertebrae, I’d found two dark rocks. To make them the vertebrae that they really were would require work, and that’s the moral of the story. All we experience is the appearance of things. The real world takes time and work and analysis and a well-schooled, disciplined, imagination. But I was already lagging behind. So I too picked up my gear and headed back toward the car.”

“That’s really a drag, but I think I see what you mean by the difference between what we see with our eyes and what we see with our understanding.”

“No problem … I’ll just carry on.”

There are wonders to nature, such as the Grand Canyon or the Great Barrier Reef, where we are overwhelmed by nature’s colors and proportions. But there are other wonders, such as black holes, ice ages, and the intricacies of molecular genetics, where the color and proportions rest in our reason, in our capacity to conjure up what things must be like in keeping with argument and analysis. Without the reasoned imagination Playfair spoke of, our world would be bleak and bleached out.

Years ago, T.H. Huxley suggested that, for most of us, the world is like walking through an art gallery where most of the paintings have been turned to the wall (Huxley, 1907, #80). We lack the feel, the insight that can evoke the wealth all around us. That is what expertise is all about. I had a colleague who had grown up on a farm. He told of watching his father pick up the soil and work it in his fingers, and from that his father could tell what fertilizer to add. Any such expertise will turn some of Huxley’s paintings around, but I readily confess … the capacity to see the abyss of time, or to know those rocks as vertebrae, that would be especially sweet.

The sciences are filled to the brim with notions like “the Earth is a planet” or that “life has evolved”—notions invented in order to explain phenomena such as those two dark rocks on that bleached out hillside in Colorado. But these ideas are far from obvious. Presented outside the context of the puzzles that prompted them and without the support of the arguments that carry them, these...