eBook - ePub

Bipolar Disorder

A Clinician's Guide to Treatment Management

- 644 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bipolar Disorder

A Clinician's Guide to Treatment Management

About this book

First published in 2009. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bipolar Disorder by Lakshmi N. Yatham, Vivek Kusumakar, Lakshmi N. Yatham,Vivek Kusumakar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Psychiatry & Mental Health. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter one

Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypomania and Mania

Contents

Mania: Diagnosis issues

Hypomania: Diagnostic issues

The management of mania and hypomania

Assessment

Initial steps, medical examination and relevant investigations

Treatment strategies in mania

Treatment strategies in hypomania

References

Mania: Diagnosis Issues

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ([DSM-IV], American Psychiatric Press, 1994) defines a manic episode as a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week (or shorter if hospitalization is necessary), with three (four if only irritability is present) or more of the following symptoms present to a significant degree: inflated self esteem or gran-diosity; decreased need for sleep; more talkative than usual; flight of ideas or a subjective experience that thoughts are racing; distractibility by unimportant and irrelevant external stimuli; increase in goal directed activity or psychomotor agitation; and an excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful or negative consequences. The mood disturbance must be sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in occupational and social functioning, sometimes requiring hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, and may be accompanied by psychotic symptoms. Although the DSM-IV definition of mania does not include those associated with pharmacologically induced states, medical or neurological conditions, these states are important to recognize as they have significant implications for assessment, investigations and management.

In general, the severe nature of mania and the marked degree of functional impairment associated with it makes it easy to distinguish from non-pathological states such as a return to euthymia after a period of depression. However, mania and manic-like symptoms can occur in psychiatric illnesses other than Bipolar I Disorder. Differentiating bipolar disorder from schizophrenia and schizoaffective illness can be a diagnostic challenge, particularly in adolescents and young adults who are having their first or early episodes. The presence of psychotic symptoms, including bizarre or mood incongruent delusions and Schneiderian first rank symptoms, is consistent with a mania as long as there are concurrent and substantial mood symptoms as well. Cross-sectionally, acute symptoms of irritability, anger, paranoia, and catatonic-like excitement are not useful in distinguishing mania from schizophrenia, and full manias can occur in patients with schizoaffective disorder. In distinguishing between bipolar illness and psychotic disorders, the clinician should consider information about family history of psychiatric illness, premorbid functioning, nature of onset of symptoms, including presence of any prodrome, and previous history of episodes of illness, including functioning during inter-episode periods. In particular, obtaining a family history of bipolar disorder and a history of episodic illness with good interepisode functioning are helpful in confirming the diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Mixed states, which constitute up to 30–40% of all manic episodes, can also pose diagnostic challenges. There are varied definitions of mixed mania in different diagnostic systems, and patients experiencing mixed episodes can present with a confusing mixture of manic and depressive symptoms. The lack of clear operationalized criteria can make it difficult to distinguish mixed mania from, for example, a major depressive episode with prominent psychomotor agitation or significant anxiety. As well, mixed states may represent a severe stage of mania, an intermediate or transitional state between mania and depression, or a distinct state that is a true combination of depressive and manic syndromes. The diagnostic and clinical implications of mixed states are summarized by Keck et al. (1996), and Freeman and McElroy (1999). The definitions of mixed states range from presence of full depressive episode to any depressive symptom in association with a manic episode. DSM-IV-TR defines mixed episode as patients meeting criteria for both depressive and manic episodes (except duration criteria) nearly every day for at least a 1-week period. However, it is increasingly accepted that the DSM-IV-TR definition of a mixed state is restrictive and arbitrary. The recognition of a wider spectrum of mixed states is not only important diagnostically but also has management implications, as mixed states are often associated with a turbulent course and increased suicidal risk, and a relatively poorer response to lithium and a better response to valproate and carbamazepine (The Depakote Mania Study Group, 1994; McElroy et al., 1992, Swann et al., 1997, Swann et al., 1999). McElroy and colleagues (1992) have devised operational criteria, which offer a compromise between the DSM-IV definition and other definitions that are overinclusive. They define dysphoric mania by presence of two or more specific depressive symptoms such as depressive mood, markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities, substantial weight gain or an increase in appetite, psychomotor retardation, hypersomnia, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or excessive inappropriate guilt, feelings of helplessness or hopelessness, recurrent thought of death or suicide.

Hypomania: Diagnostic Issues

Hypomania may occur as part of Bipolar II Disorder, or as a transitional state from euthymia to mania in patients with Bipolar I Disorder. A hypo-manic episode, as per the DSM-IV-TR, consists of a period of elevated, expansive or irritable mood plus at least three (four, if only irritable) additional manic symptoms, lasting for a minimum of four days, and observed as a change from baseline by others. By definition, hypomania is not associated with marked impairment, hospitalization or psychotic features. Clinicians are aware that hypomania may, in fact, be associated with little or no functional impairment, or even represent a period of super-normal functioning. In addition, the criterion that symptoms should last for at least 4 days is arbitrary, and clinically relevant hypomanias may be missed with this criterion as hypomanic symptoms can often last for 1–3 days (Wicki & Angst, 1991; Yatham, 2005; Hadjipavlou et al., 2004). Clinicians should also note that many patients may simply show a decreased need for sleep and an increased energy and drive, which may all be masked within a socially or occupationally acceptable spectrum, particularly in adolescents, young adults and those in situations where a “driven” life style may be seen as acceptable or even desirable.

Bipolar II Disorder is frequently misdiagnosed as Major Depressive Disorder. The under-recognition of Bipolar II Disorder in research and clinical settings is largely attributable to the difficulty associated with obtaining a clear history of hypomania. Patients suffering from Bipolar II Disorder experience depression much more frequently than hypomania, and seek help almost exclusively during depressive episodes. Furthermore, individuals with Bipolar II Disorder may not recall previous hypomanic episodes, may not be able to distinguish them from euthymia, or even see them as desirable. Hence, it is incumbent on all physicians to retain a high index of suspicion for Bipolar II Disorder in any patient with apparent recurrent Unipolar Depression, and clinicians should carefully question all depressed patients about elevated mood states (Yatham, 2005). Careful history taking has been demonstrated to lead to a correct diagnosis of Bipolar II Disorder by experienced clinicians. Dunner and Day (1993) reported that an expert clinician using a semi-structured interview, when compared with a non-physician trained interviewer who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), assigned a Bipolar II diagnosis much more often than did the less experienced interviewer. In routine clinical practice, other methods that can be used to increase the likelihood of correctly diagnosing Bipolar II Disorder include obtaining collateral information from family members, using validated questionnaires such as the Mood Disorders Questionnaire, and having patients keep a regular mood diary. Finally, clinicians should be alert for “warning signs” of bipolarity in depressed patients, including especially a family history of bipolar disorder and a history of antidepressant-associated manias or hypomanias. Additional predictors of bipolarity include early onset of depression, short (< 3 months) depressive episodes, highly recurrent depressions, atypical depressive symptoms, a seasonal pattern to mood episodes, acute but not sustained response to antidepressants, and the presence of mixed depressive and hypomanic symptoms (Yatham, 2005).

Data from an ongoing genetic linkage study of Bipolar I families suggests that Bipolar II Disorder may be the most common phenotype or clinical manifestation in both Bipolar I and Bipolar II families (Simpson et al., 1993). Thus, there is some support for the clinical impression that Bipolar II Disorder may be more common than Bipolar I Disorder. Further, Bipolar II Disorder often tends to breed true to type: offspring and relatives of Bipolar II probands commonly also have Bipolar II Disorder (DePaulo et al., 1990), and genetic (Dunner, Gershon, & Goodwin, 1976), family history (Heun & Maier, 1993) and treatment studies (Calabrese et al., 2000) also suggest that Bipolar II Disorder is distinct from Bipolar I Disorder. Hence, a careful screening for a family history of Bipolar II Disorder can assist in diagnosis of a given patient. However, the clinician should also be careful not to diagnose bipolar disorder in patients, particularly those with borderline personality disorder, who often have uniphasic mood lability in the depressive to euthymic spectrum, and who may mistakenly describe euthymic states as “highs” (Akiskal, 1996). It is, however, important to bear in mind that borderline personality disorder can be comorbid with bipolar disorder in up to 30% of patients with bipolar disorder. The clinician is also well advised to be cautious in interviewing patients with Somatization Disorder with depressive symptoms, as these patients can be highly suggestible, thus resulting in false positive assessments of hypomanic symptoms. Conversely, adolescent and young adult patients with rapid and ultra rapid biphasic mood cycling may be mistakenly diagnosed as having a primary borderline personality disorder. To safeguard against this, prospective mood charting and careful collateral histories and observations from friends and family members can be vital.

Although clear-cut mixed states are classified in the DSM-IV under mania, hypomanic patients may also suffer from dysphoric symptoms. Bipolar II Disorder, on average, has an earlier age of onset than does non-bipolar depression (Akiskal et al., 1995). This is particularly important as acts of deliberate self-harm in adolescents and young adults warrant an assessment for Bipolar II Disorder. Bipolar II patients are more likely than non-bipolar Major Depressive Disorder patients to have a history of suicide attempts (Kupfer, Carpenter, & Frank, 1988). Despite the turbulence that hypomania and recurrent depression can cause in Bipolar II patients, these patients are less likely to be hospitalized although the psychosocial impairment, risk of suicide and other functional morbidity may be significant in the Bipolar II group as well (Cook et al., 1995). Bipolar II patients also have a greater liability to rapid cycling.

The Management of Mania and Hypomania

Assessment

The principles that guide the management of mania and hypomania include choosing a setting for treatment which will assure the safety of the patient and adherence with the treatment plan; prescribing medications which will rapidly reduce manic symptoms, protect against mania and depression during long-term treatment, and cause minimal side effects; and promoting a return to full psychosocial functioning. In the initial assessment of the patient, it is important to be aware that patients experiencing hypomania or mania often have a loss of insight fairly early in the course of the episode. Hence, obtaining collateral information from friends and relatives is vital. Clinicians should routinely screen for concurrent symptoms of depression and more complex mixed states, as well as for psychotic symptoms, suicidality, aggression, impulsive behaviors such as overspending, and dangerousness with or without homicidality. Observer rating scales have been commonly used in clinical research studies, and are increasingly being used to measure change and response to treatment in ordinary clinical settings. Rating scales that take into account patient reports, informant reports, and clinical staff observations are likely the most valid in establishing or ruling out the variety of symptoms that are present in a mania. For a review of a variety of rating scales refer to Goodwin and Jamieson (2007). Knowledge regarding the patient’s psychiatric history, including severity of previous episodes and response to treatment trials, and medical history, including allergies, is also crucial. Noting the patient’s mental state, particularly with respect to insight and judgment, and any evidence of psychosis, agitation, aggression, or threatening behavior, is important in assessing safety.

Initial Steps, Medical Examination and Relevant Investigations

An important and necessary first step is to ascertain if the manic patient is able to give consent to treatment. If not, valid consent should be obtained as soon as possible from a person recognized in local law to be able to do so. Ensuring the safety of the acutely manic patient and those around him/her is a high priority at all stages of treatment. Hence, the initial steps may well involve screening for and managing an overt or covert attempt at suicide or other deliberate self harm, particularly by overdose. Patients who are aggressive and combative would benefit not only from being in a low stimulus, comfortable and non-challenging environment but also from rapid institution of medications to manage behavior dyscontrol and aggression. The clinician is well advised to confirm or rule out, early on in treatment, any reasonable possibility of mania secondary to an underlying medical condition, current or recent substance use and pharmacologically induced mania. Ideally, a medical evaluation and baseline investigations should be completed before the institution of biological treatment. In certain circumstances, however, because of a very acute clinical situation, treatment may have to begin prior to the completion of a full medical workup. Apart from a thorough medical examination, the following baseline investigations should be completed (Yatham et al., 2005): complete blood count including platelets; serum electrolytes; liver enzymes and serum bilirubin; urinalysis and urine toxicology for substance use; serum creatinine, and, if there is any personal or family history of renal disorder, a 24 hour creatinine clearance; TSH; ECG in patients over 40 years of age or with a previous history of cardiovascular problems; and a pregnancy test where relevant.

Serum levels of mood stabilizers should be obtained at the trough point, approximately 12 hours after the last dose of medication, at admission (as many patients are non-compliant with medications in the days or weeks leading up to an acute manic episode), and approximately 5–7 days after achieving a mood stabilizer dose titration. Two consecutive serum levels within the therapeutic range (0.8–1.2 mmols/l for lithium or 350–700 µmols/l for valproate) are sufficient during the acute phase. Any additional serum level monitoring is better guided by the clinical need and clinical state of the patient. There is no evidence that blood counts and liver enzymes need to be done more frequently than at baseline, at the end of 4 weeks and once every 6 months thereafter, unless there is a specific clinical concern. Closer monitoring is, however, required in children and the elderly, in patients being treated with multiple medications, or in any patients where there is legitimate clinical concern about hematological, hepatic, renal, endocrine, cardiovascular or neurological dysfunction.

Treatment Strategies in Mania

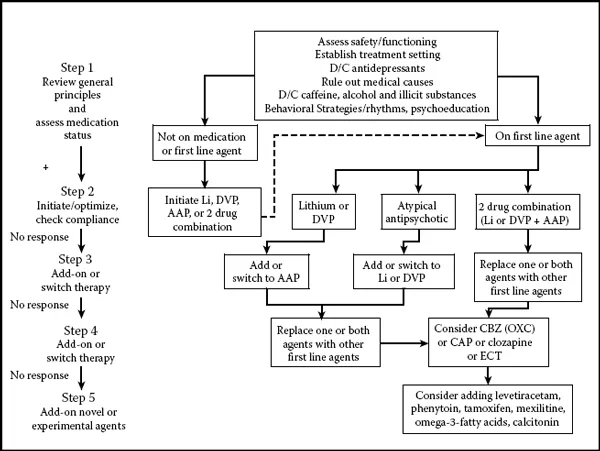

The reader is advised to refer to the chapters in this book on lithium (Chapter 10), anticonvulsants (Chapter 13), antipsychotics (Chapter 11), somatic treatments including ECT (Chapter 14), and pharmacokinetics and drug interactions (Chapter 17), for up to date reviews on the evidence of efficacy, common adverse effects and dosing strategies with various treatments. These reviews form the basis for the rationale in designing treatment strategies. However, outlined here is a summary of commonly asked questions and issues that underpin the treatment of hypomania and mania, followed by some treatment algorithms (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Treatment algorithm for acute mania. AAP, atypical antipsychotic; CB...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Contributors

- Chapter 1. Diagnosis and treatment of hypomania and mania

- Chapter 2. Bipolar depression: Diagnosis and treatment.

- Chapter 3. Diagnosis and treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder

- Chapter 4. Bipolar II disorder: Assessment and treatment

- Chapter 5. Maintenance treatment in bipolar I disorder

- Chapter 6. Bipolar disorders in women: Special issues

- Chapter 7. Bipolar disorder in children and adolescents

- Chapter 8. Bipolar disorder in the elderly

- Chapter 9. Comorbidity in bipolar disorder: Assessment and treatment

- Chapter 10. Lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder

- Chapter 11. Antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder: A critical review of randomized controlled trials

- Chapter 12. Antidepressants for bipolar disorder: A review of efficacy

- Chapter 13. Anticonvulsants in treatment of bipolar disorder: A review of efficacy

- Chapter 14. Somatic treatments for bipolar disorder

- Chapter 15. Psychotropic medications in bipolar disorder: Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, adverse effects and their management

- Chapter 16. Practical issues in psychological approaches to individuals with bipolar disorders

- Chapter 17. Psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder: A critical review of evidence for efficacy

- Chapter 18. Novel treatments in bipolar disorder: Future directions

- Index