- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

AQA Religious Ethics for AS and A2

About this book

Structured directly around the specification of the AQA, this is the definitive textbook for students of Advanced Subsidiary or Advanced Level courses. It covers all the necessary topics for Religious Ethics in an enjoyable student-friendly fashion. Each chapter includes:

- a list of key issues

- AQA specification checklist

- explanations of key terminology

- helpful summaries

- self-test review questions

- exam practice questions.

To maximise students' chances of exam success, the book contains a section dedicated to answering examination questions. It comes complete with lively illustrations, a comprehensive glossary, full bibliography and a companion website.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access AQA Religious Ethics for AS and A2 by Jill Oliphant, Jon Mayled,Anne Tunley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 What Is Ethics?

Ethics is the philosophical study of good and bad, right and wrong. It is commonly used interchangeably with the word ‘morality’, and is also known as moral philosophy. The study of ethics requires you to look at moral issues such as abortion, euthanasia and cloning, and to examine views that may be quite different from your own. You need to be open-minded, you need to use your critical powers, and above all learn from the way different ethical theories approach the issues you study for AS and A2.

Ethics needs to be applied with logic so that we can end up with a set of moral beliefs that are supported with reasons, are consistent and reflect the way we see and act in the world. Ethical theories are constructed logically, but give different weights to different concepts. However, it is not enough to prove that the theory you agree with is true and reasonable; you must also show where and how other philosophers went wrong.

FALLACIES

With the possible exception of you and me, people usually do not have logical reasons for what they believe. This is especially true for ethical issues. Here are some examples of how not to arrive at a belief. We call them fallacies. Here are some common beliefs:

- a belief based on the mistaken idea that a rule which is generally true is without exceptions; for example: ‘Suicide is killing oneself – killing is murder, I'm opposed to euthanasia’

- a belief based on peer pressure, appeal to herd mentality or xenophobia; for example: ‘Most people don't believe in euthanasia, so it's probably wrong’

- a belief in fact or obligation simply based on sympathy; for example: ‘It's horrible to use those poor apes to test drugs, I'm opposed to it’

- an argument based on the assumption that there are fewer alternatives than actually exist; for example: ‘It's either euthanasia or long, painful suffering’

- an argument based on only the positive half of the story; for example: ‘Animal research has produced loads of benefits – that's why I support it’

- hasty generalisation: concluding that a population has some quality based on a misrepresentative sample; for example: ‘My grandparents are in favour of euthanasia, I would think that most old people would agree with it’

- an argument based on an exaggeration; for example: ‘We owe all of our advances in medicine to animal research, and that's why I'm for it’

- the slippery slope argument: the belief that a first step in a certain direction amounts to going far in that direction; for example: ‘If we legalise euthanasia this will inevitably lead to killing the elderly, so I'm opposed to it’

- an argument based on tradition: the belief that X is justified simply because X has been done in the past; for example: ‘We've done well without euthanasia for thousands of years, we shouldn't change now.’

IS–OUGHT FALLACY

David Hume (1711–1776) observed that often when people debate a moral issue they begin with facts and slide into conclusions that are normative; that is, conclusions about how things ought to be. He argued that no amount of facts taken alone can ever be sufficient to imply a normative conclusion: the is–ought fallacy. For example, it is a fact that slavery still exists in some form or other in many countries – that is an ‘is’. However, this fact is morally neutral, and it is only when we say we ‘ought’ to abolish slavery that we are making a moral judgement. The fallacy is saying that the ‘ought’ statement follows logically from the ‘is’, but this does not need to be the case. Another example is to say that humans possess reason and this distinguishes us from other animals – it does not logically follow that we ought to exercise our reason to live a fulfilled life.

Ethics looks at what you ought to do as being distinct from what you may in fact do. Ethics is usually divided into three areas: meta-ethics, normative ethics and applied ethics.

- Meta-ethics looks at the meaning of the language used in ethics, and includes questions such as: are ethical claims capable of being true or false, or are they expressions of emotion? If true, is that truth only relative to some individual, society or culture?

- Normative ethics attempts to arrive at practical moral standards that tell us right from wrong, and how to live moral lives. These are what we call ethical theories. This may involve explaining the good habits we should acquire, looking at whether there are duties we should follow, or whether our actions should be guided by their consequences for ourselves and/or others.

- Applied ethics is the application of theories of right and wrong and theories of value to specific issues such as abortion, euthanasia, cloning, foetal research, and lying and honesty.

Normative ethics may be further divided into deontological and teleological ethical theories.

- Deontological ethics. Deontological ethical theories claim that certain actions are right or wrong in themselves regardless of the consequences. Examples of deontological theories considered in this book are: Natural Law, Kantian ethics and Divine Command theory.

- Teleological ethics. Teleological ethical theories look at the consequences or results of an action to decide if it is right or wrong. Examples of teleological theories considered in this book are Utilitarianism and Situation ethics.

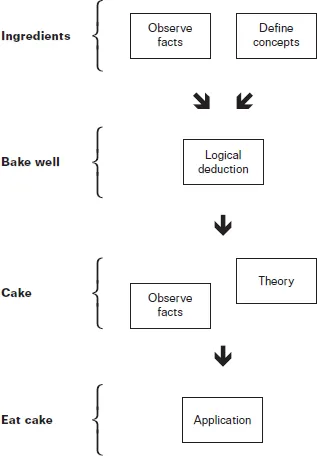

Ethics is not just giving your own opinion, and the way it is studied at AS and A2 is very like philosophy: it is limited to facts, logic and definition. Ideally, a philosopher is able to prove that a theory is true and reasonable on the basis of accurate definitions and verifiable facts. Once these definitions and facts have been established, a philosopher can develop the theory through a process of deduction, by showing what logically follows from the definitions and facts. The theory may then be applied to controversial moral issues.

ETHICAL THEORIES

If we are to have valid ethical arguments then we must have some normative premises to begin with. These normative premises are either statements of ethical theories themselves or statements implied by ethical theories.

The ethical theories that will be examined in this book are:

- Utilitarianism: An action is right if it maximises the overall happiness of all people.

- Kantian ethics: Treat other people the way you wish they would treat you, and never treat other people as if they were merely objects.

- Cultural relativism: What is right or wrong varies according to the beliefs of each culture.

- Divine Command: Do as the creator tells you.

- Natural Law: Everything is created for a purpose, and when this is examined by human reason a person should be able to judge how to act in order to find ultimate happiness.

- Situation Ethics: Based on agape (see p. 28) which wills the good of others.

- Virtue Ethics: Agent-centred not act-centred. Practising virtuous behaviour will lead to becoming a virtuous person and contribute to a virtuous society.

AS UNIT A

RELIGION AND

ETHICS 1

2 Utilitarianism

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN ABOUT IN THIS

CHAPTER

- The principle of utility, the hedonic calculus, Act and Rule Utilitarianism.

- Classical forms of Utilitarianism from Bentham, Mill and Sidgwick; modern versions from Hare and Singer.

- The strengths and weaknesses of Utilitarianism.

- How to apply Utilitarianism to ethical dilemmas.

| THE AQA CHECKLIST |  |

The general principles of Utilitarianism:

- Consequential or teleological thinking in contrast to deontological thinking

- Bentham's Utilitarianism, Act Utilitarianism, the hedonic calculus

- Mill's Utilitarianism, Rule Utilitarianism, quality over quantity

- The application of Bentham's and Mill's principles to one ethical issue of the candidate's choice apart from abortion and euthanasia.

ISSUES ARISING

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the ethical systems of Bentham and Mill?

- Which is more important – the ending of pain and suffering, or the increase of pleasure?

- How worthwhile is the pursuit of happiness, and is it all that people desire?

- How compatible is Utilitarianism with a religious approach to ethics?

WHAT IS UTILITARIANISM?

You have probably heard someone justify their actions as being for the greater good. Utilitarianism is the ethical theory behind such justifications.

Utilitarianism is a teleological theory of ethics. Teleological theories of ethics look at the consequences – the results of an action – to decide whether it is right or wrong. Utilitarianism is a consequentialist theory. It is the opposite of deontological ethical theories that are based on moral rules, on whether the action itself is right or wrong.

The theory of Utilitarianism began with Jeremy Bentham as a way of working out how good or bad the consequence of an action would be. Utilitarianism gets its name from Bentham's test question: ‘What is the use of it?’ He thought of the idea when he came across the words ‘the greatest happiness of the greatest number’ in Joseph Priestley's An Essay on the First Principles of Government; and on the Nature of Political, Civil, and Religious Liberty (1768). Bentham was very concerned with social and legal reform and he wanted to develop an ethical theory which established whether something was good or bad according to its benefit for the majority of people. Bentham called this the principle of utility. Utility here means the usefulness of the results of actions. The principle of utility is often expressed as ‘the greatest good of the greatest number’. ‘Good’ is defined in terms of pleasure or happiness – so an act is right or wrong according to the good or bad that results from the act, and the good act is the most pleasurable. Bentham's theory is quantitative because of the way it considers a pleasure as a quantifiable entity.

Teleological

According to teleological theories, moral actions are right or wrong according to their outcome or telos (end).

THE ORIGINS OF HEDONISM

The idea that ‘good’ is defined in terms of pleasure and happiness makes utilitarianism a hedonistic theory. The Greek philosophers who thought along similar lines introduced the term eudaimonia, which is probably best translated as the harmonious well-being of life. Both Plato and Aristotle agreed that ‘good’ equated with the greatest happiness, while the Epicureans stressed ‘pleasure’ as the main aim of life. The ultimate end of human desires and actions, according to Aristotle, is happiness and, though pleasure sometimes accompanies this, it is not the chief aim of life. Pleasure is not the same as happiness, as happiness results from the use of reason and cultivating the virtues. It is only if we take pleasure in good activities that pleasure itself is good. This idea of Aristotle's is taken up by John Stuart Mill, as we will see later.

Consequentialist

Someone who decides whether an action is good or bad by its consequences.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- How to Use this Book

- Answering Examination Questions

- Timeline: Scientists, Ethicists and Thinkers

- 1 What Is Ethics?

- As Unit A Religion And Ethics 1

- As Unit B Religion And Ethics 2

- A2 Unit 3A Religion And Ethics

- Unit 4C

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index