eBook - ePub

Modern Architecture and the Mediterranean

Vernacular Dialogues and Contested Identities

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Modern Architecture and the Mediterranean

Vernacular Dialogues and Contested Identities

About this book

Bringing to light the debt twentieth-century modernist architects owe to the vernacular building traditions of the Mediterranean region, this book considers architectural practice and discourse from the 1920s to the 1980s. The essays here situate Mediterranean modernism in relation to concepts such as regionalism, nationalism, internationalism, critical regionalism, and postmodernism - an alternative history of the modern architecture and urbanism of a critical period in the twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Modern Architecture and the Mediterranean by Jean-Francois Lejeune, Michelangelo Sabatino, Jean-Francois Lejeune,Michelangelo Sabatino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Architettura generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

SOUTH

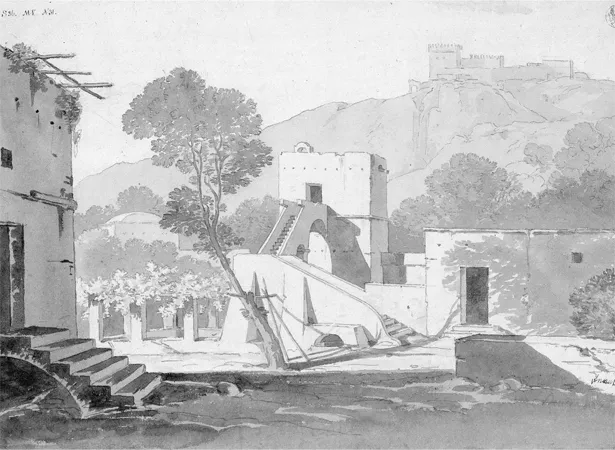

1.1 (Far left)Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Farmhouse in Capri, 1804.

Source: © Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz/ Art Resource, Inv. SM 5.31. Photo J. P. Anders.

1

FROM SCHINKEL TO LE CORBUSIER

The Myth of the Mediterranean in Modern Architecture

Benedetto Gravagnuolo

When we say Mediterranean we mean above all the solar stupor that generates the panic-stricken myth and the metaphysical immobility.1

It is with these words pregnant with esoteric suggestions that Massimo Bontempelli attempted an acrobatic definition of the “myth of the Mediterranean” — a myth that exercised a notable magnetic force on the artistic, literary, and architectonic debate in Italy, Spain, and France in the first decades of the 1900s.2 Carlo Belli, a witness and actor of the period, wrote:

The theme of “Mediterranean-ness” and “Greek-ness” was our navigational star. We discovered early that a bath in the Mediterranean would have restored to us many values drowned under gothic superimpositions and academic fantasies. There is a rich exchange of letters between Pollini, Figini, Terragni and myself on this subject. There are my articles in various journals, especially polemical with Piacentini, Calza Bini, Mariani and others embedded in Roman fascism … We studied the houses of Capri: how they were constructed, why they were made that way. We discovered their traditional authenticity, and we understood that their perfect rationality coincided with the optimum of aesthetic values. We discovered that only in the ambit of geometry could one actuate the perfect gemütlich of dwelling.3

Without a doubt, mediterraneità — not to be confused with romanità to which it was often polemically counterpoised — represented an explicit font of inspiration from which a small circle of initiates, mostly French and Italian, drew. Yet, before entering into an evaluation of the merit of this ideology — and analyzing the verbal and visible alchemies of the “disquieting muses” — it may be useful to pose a few basic questions.4 Does there exist a “Mediterranean culture of living”? And, if it exists, in what measure is it recognizable as a historical phenomenon? And lastly, is it possible to reassert it in terms of a collective design ethos? It is not easy to respond to these questions, but it is worth reducing the discourse to its schematic essence.

The mare nostrum or Mediterranean has represented for centuries a privileged cradle of commercial exchange, bellicose conflicts, and cultural transmissions. On its shores ancient historical civilizations flowered — including Egyptian, Cretan-Mycenaean, Phoenician, and Greek — and on its waters the first empires were founded — Carthaginian, Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic. Many affinities of climate, traditions, topography, and even ethnic traits are visible along the coastlines of countries facing the Mediterranean. Among the various anthropological manifestations, the one that best registers and preserves the

1 Massimo Bontempelli, Introduzioni e discorsi, Milano, Bompiani, 1945, p. 171. Bontempelli was the founder and the director of two periodicals: 900, in collaboration with Curzio Malaparte (1926–29) and Quadrante, in collaboration with Pier Maria Bardi (1933–36). In these periodicals and his numerous books, he established the theoretical basis of “magical realism.” In so doing, he became a pole of reference for the “classical” and “metaphysical” cultural movements.

2 For a more extensive bibliography, see Carlo Enrico Rava, Nove anni di architettura vissuta, 1926–1935, Roma, Cremonese, 1935, and, in particular, the essay titled “Architettura ‘europea,’ ‘mediterranea,’ ‘corporativa,’ o semplicemente italiana,” pp. 139–150. Also see Carlo Belli, “Lettera a Silvia Danesi,” in Silvia Danesi and Luciano Patetta (eds.), Il razionalismo e l'architettura in Italia durante il Fascismo, Venezia, Biennale di Venezia, 1976, pp. 21–28; Benedetto Gravagnuolo, “Colloquio con Luigi Cosenza,” in Modo 60, June–July 1983.

3 Carlo Belli, “Lettera a Silvia Danesi,” p. 25.

4 See Manfredo Tafuri, “Les ‘muses inquiétantes' ou le destin d'une génération de ‘maîtres'”, in L'architecture d'aujourd'hui, 181, 1975.

signs of a transnational civilization is architecture. Not the cultured or high architecture but rather the vernacular architecture, an expression of constructive, repetitive, and choral techniques sustained by a collective culture of living that settled over the course of centuries.

However, once the legitimacy of the “civilization of the Mediterranean” has been recognized as a subject of historical analysis — particularly in the pioneering work of Fernand Braudel — it remains to be asked whether and up until what point does such a civilization demonstrate unifying features?5 For it is clear that — despite both the presence of a cradle of communal exchange and the permanence of techniques and forms tied to a longue durée — the towns and buildings along the Mediterranean coasts have not only developed in relation to different local specificities but also have incurred in time many transformations that cannot be underestimated. Braudel asked the question:

What is the Mediterranean? It is one thousand things at the same time. Not one landscape but innumerable landscapes. Not a sea, but a succession of seas. Not a civilization, but civilizations amassed on top of one another. To travel within the Mediterranean is to encounter the Roman world in Lebanon, prehistory in Sardinia, the Greek cities in Sicily, the Arab presence in Spain, Turkish Islam in Yugoslavia. It is to plunge deeply into the centuries, down to the megalithic constructions of Malta or the pyramids of Egypt. It is to meet very old things, still alive, that rub elbows with ultra-modern ones: beside Venice, falsely motionless, the heavy industrial agglomeration of Mestre; beside the boat of the fisherman, which is still that of Ulysses, the dragger devastating the sea-bed, or the huge supertankers. It is at the same time to immerse oneself in the archaism of insular worlds and to marvel in front of the extreme youth of very old cities, open to all the winds of culture and profit, and which, since centuries, watch over and devour the sea.6

This plurality of cultures, languages, and ethnicities — woven into tight and complex knots — can then be disentangled in a historical setting. But in the field of design, mediterraneità can only be re-proposed — or, at least, it has always been re-proposed that way — through a mytho-poetic transfiguration and an acknowledged invention. Massimo Bontempelli clarified this mechanism in his typical Machiavellian mysticism:

It is necessary to invent. The ancient Greeks invented beautiful myths and fables that humanity has used for several centuries. Then Christianity invented other myths. Today we are at the threshold of a third epoch of civil humanity. And we must learn the art of inventing new myths and new fables.7

The deceit that the Mediterranean myth dispenses is, in fact, the transhistorical representation of the past as present. It insinuates the elegant assumption of the eternal, beyond the cyclical mutation of the seasons, beyond the perennial alternating of day and night, and the infinite forms across which time shows itself, almost as if the art of each epoch were measured with a unique theme: the desire for harmony. And it is exactly as myth, as a desire for simple and harmonious construction, as a simulacrum of absences of decorum and pure Euclidean volumes, as symbolic expression of the arithmetic canons of “divine proportion,” as a shade of Apollonian beauty and as an echo of sirens transmitted on the waves of the sea, that the concept of mediterraneità can and must be evaluated beyond its objective verifiability.

5 See Fernand Braudel, La Méditerranée et le Monde méditerranéen à l'époque de Philippe II, Paris, Armand Collin, 1949. In English, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, London, Fontana/Collins, 1972.

6 Fernand Braudel, La Méditerranée, l'espace et l'histoire, Paris, 1977, p.7 [Editor's translation]. In the chapter “Novecentismo e opzione classica” of his monograph on José Luis Sert, 1901–1983, Milano, Electa, 2000, Rovira discusses Braudel's research and book as an attempt to counteract the simplistic and propagandistic mythification of the Mediterranean. He also sees the timing as important, at the moment of the post-World War II political and physical reconstruction.

7 Massimo Bontempelli, “Realismo magico,” in 900, July 1928; also in Luciano Patetta (ed.), L'architettura in Italia, 1919–1943. Le polemiche, Milano, Clup, 1972, p. 90.

In European culture this myth has exercised an extraordinary evocative force on some of the theories of “rational” architecture, beginning with the eighteenth-century rediscovery of the goût grec.8 It is often said that it was the discovery of a statue of Hercules by the Austrian prince d'Elboeuf in the year 1711 at Herculaneum that the enthusiastic re-evaluation of the “noble simplicity and calm greatness” of the classical ancient civilization of the Mediterranean began.9 Besides, we know that Anton Raphael Mengs, who jokingly passed off a false representation of Giove e Ganimede (Jupiter and Ganym...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- North versus South

- Part I: SOUTH

- Part II: NORTH

- Index