- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Historical Atlas of Women in America

About this book

Looking at general trends and specific items such as life in a tenement, women working overseas in World War I, the production of cosmetics in the 1920s, and new female immigration, this atlas portrays the history of American women from a vivid geographical and demographic perspective. In a variety of colorful maps and charts, this important new work documents milestones in the evolution of the social and political rights of women. Coverage includes the rise of reform movements such as temperance, women's suffrage, and abolition during the 19th century, and contraception, abortion rights, and the Equal Rights Amendment in the 20th. Also inlcludes 50 color maps.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Routledge Historical Atlas of Women in America by Sandra Opdycke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: Breaking Old Ties:

American Women Before 1800

During the years before 1800, hundreds of thousands of women left their old lives behind in Europe or Africa and began building new ones in North America. Once they arrived on the new continent, the process of breaking old ties and constructing new ones continued. Each time a woman and her family left the place they knew to move further west, or a slave watched her husband sold away, or a mother stood over her baby's grave, or one of the recurrent wars took a life or destroyed a village—on each of these occasions, the women involved had to accommodate the loss and start building new lives to replace the old. The ways in which they accomplished these tasks were familiar but essential: They fed and nurtured their families, they preserved the rituals that kept alive their families' connection to the past, and they formed new bonds of love and friendship to replace those that had been broken.

Even Indian women, who had been in America from the start, were forced to go through this process. On the East Coast, the rapid growth of the European colonies pushed the Indians steadily westward, not only into unfamiliar terrain but often into the territory of other tribes. In the Southwest and along the Pacific coast, the Spanish conquest had a similar impact, unsettling Indian life with military raids, religious missions, and forced agricultural labor. Furthermore, all across the North American continent, even among inland tribes that rarely encountered a European face to face, the ways in which Indian women had lived and worked for generations were gradually transformed by the spread of European diseases, trade goods, guns, and horses. Indian society would continue to flourish for many years to come, but the growing pressures on that society were clearly visible by 1800.

African women who were brought to the New World as slaves during these years experienced the most violent dislocation of all. From the arrival of the first slaves in North America in 1619 to the outlawing of importation in 1807, thousands of black women were taken forcibly from their villages. They were then subjected to imprisonment on the African coast, a grim passage across the Atlantic, sale on the auction block in some North American port, and the arduous process of learning to be a slave. Furthermore, even as these women struggled to adapt to their new surroundings, the connections they established were frequently broken again as family and friends were sold away to other masters. Within the iron constraints that surrounded them, female slaves did manage to carve out a space for personal and family life, but no group of American women performed that task under more difficult circumstances.

The white women who came to the New World from Europe had more choice in the matter than the black women brought from Africa, and for some of them, the journey to America represented a welcome chance to start anew, in a freer society than the Old World had offered. Yet nearly all the women who sailed from Europe left behind people and places that were dear to them, and many would probably have chosen to remain at home if they could. Most female convicts, for instance, could be considered voluntary emigrants only in the sense that they preferred a life of exile to death on the gallows. Other women made the trip because poverty or religious oppression made it impossible for them to stay where they were. And perhaps the greatest number—ranging all the way from noblewomen to housemaids—undertook the voyage primarily because the men who made the decisions in their lives had determined that the family should go to America.

In this colonial kitchen, several women (and one elderly man) go about a variety of household tasks: spinning, pie-making, grilling, churning, and keeping an eye on the children.

Having settled in the colonies, these white women encountered still more change and disruption. First, there were the upheavals that most women lived with during these years: epidemics, natural disasters, deaths in the family. Each time one of these cataclysms struck, old connections were broken and it became necessary to build again. A second source of instability was the continual flow of people moving westward. As the population increased and as land along the coast became more expensive, many a colonial family picked up stakes and moved again, or watched their children or their friends set out to find new opportunity along the frontier. Each arrival and departure unsettled old relationships while making new ones possible.

Starting around the middle of the eighteenth century, colonial women experienced a third source of instability: the rupture of the ties between Britain and her North American colonies. The troubled years leading up to the American Revolution caused bitter divisions within colonial society and culminated by breaking one of the most time-honored ties of all: the connection between the king and his subjects. The fight for independence drew many women into unfamiliar roles in political (and sometimes military) affairs, further alienated the patriots from the Indians who sided with the British, exposed thousands of American families to the depredations of war, and drove hundreds of loyalist families into exile. Once the war ended, women's roles were not very different from what they had been before, but the colonial society within which they had performed those roles was replaced by the young republic, and that change presented women with a new set of possibilities and limitations for the future.

For some American women, the repeated breaking of old ties during the years before 1800 represented liberation; for others—especially Indian and black women—it meant loss and dislocation. But as the United States entered the nineteenth century, the country owed much of its vitality to the way in which, despite constant upheavals, women of every race and class had managed to keep weaving and reweaving the social fabric that held together their families and their communities.

The First American Women

For thousands of years, Native American women constituted the entire female population of the territory that would later become the United States, Through most of prehistory, these women lived as members of small bands (usually just a few families) that maintained themselves by some combination of hunting, fishing, and gathering. Starting about 5000 B.C., the developmen! of agriculture made it possible to form larger permanent settlements—villages and even cities. Large parts of the interior were still sparsely inhabit nomadic bands, but by the time the first Europeans arrived in 1492 Indians had established significant clusters of population along the Pa coast, in the Southwest, the Southeast, in the Mississippi Valley, an along the Atlantic coast. Estimates vary, but by that time there were at least 4 million and perhaps as many as 18 million Indians living in North America north of Mexico.

Like women in many parts of the world, Native American women bore the primary responsibility for the care of their children and for preparing food and clothing. There were, however, two ways in which the lives of Native American women were quite different from those of the European women who would settle on their continent.

For one thing, in Indian society each nuclear family was part of a larger and more important group: the kinship network. The fact that in many communities several families lived under one roof and that many tribes held their land in common reflected a larger idea: that the whole kin network, rather than the nuclear family, was the linchpin of society. As a result, Native American women appear to have had access to a broader set of primary relationships than most European women enjoyed in their nuclear households. The extensive association with female kin probably reached its peak in matrilineal societies such as the Pueblos, the Iroquois, and the Cherokees. In these places, it was the men rather than the women who moved to their spouses' communities when they married; thus it was the women who remained in the community from generation to generation, maintaining the continuity of the tribe through their daughters and granddaughters.

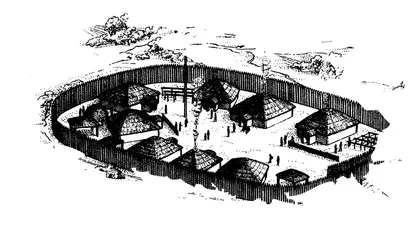

This drawing suggests what an Indian village in North Carolina might have looked like, several hundred years before the European settlers began to arrive.

A second major difference between the lives of Native American and European women lay in the fact that in most agricultural areas Indian women did virtually all the field labor, while men performed the tasks that required being away from the village: hunting, fishing, trading, fighting, and treaty making. Contemporary European observers often criticized this arrangement, maintaining that Indian men were lazy and their women overworked. Yet the women's vital role in providing food gave them higher community standing than most European women enjoyed. In many tribes, women had a considerable voice in religious or political affairs, and among some peoples such as the Pueblo, Hopi, Zuni, and Iroquois, women actually owned the fields collectively and controlled how the food was distributed.

European Women in the New World

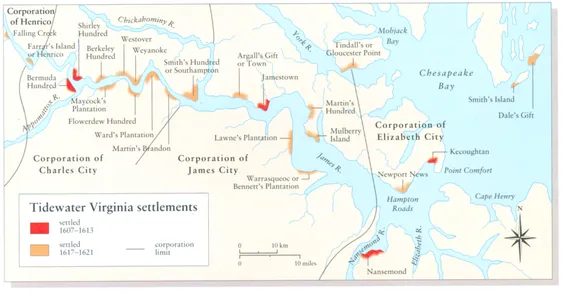

During the early 1600s, English women helped establish the first two permanent European colonies in the future United States—one in Jamestown, Virginia, and the other in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Thousands more Europeans followed, as well as a growing number of African slaves. By 1700 there were about 250,000 people in the American colonies, of whom just over 10 percent were black.

Most white female colonists of the seventeenth century, whether in the North or the South, worked as farmers' wives, presiding over a continual round of tasks involved in feeding, clothing, and caring for their families. Black women, too, generally worked on farms and oversaw the preparation of food and clothes for their families. None of these women could vote, hold church office, make a contract, or own property if she were married. Yet beyond the similarities they shared, colonial women's lives did differ by region, as can be seen if we compare the experience in Virginia and Massachusetts.

The first two women arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1608, a year after the colony's founding. Since supplies from England arrived erratically and the colonists were reluctant farmers, only the Indians' generosity kept them alive during the first difficult years. Tobacco growing emerged as Virginia's salvation, and within a few decades it attracted a flood of new immigrants from Europe. Many of the female newcomers were indentured servants, bound to six or seven years of labor. They found themselves in a society divided by growing economic inequality, shadowed by a death rate higher than the worst epidemic years in England, and moving toward a dependence on slave labor. Yet despite its problems, Virginia promised these women a better life than at home, including plenty of marriage offers when their indentures were up, since for many years the colony had far more men than women.

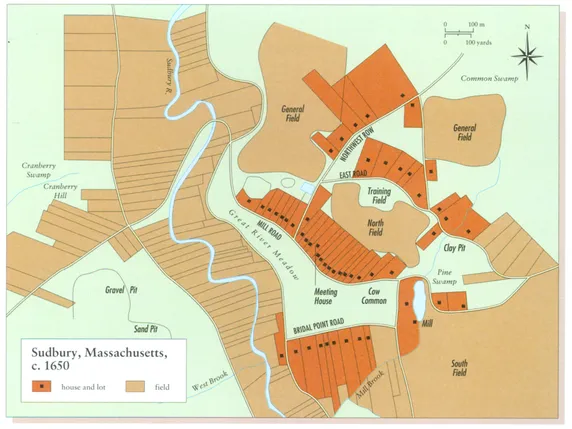

A thousand miles away in Massachusetts, the Puritans were also facing challenges, but after a desperate first winter in 1620-1621, they moved more quickly than Virginia to a condition of relative stability. For one thing, most of the Puritans immigrated in family groups, which made for a more settled community life. In addition, because most of the Puritan couples came intending to work as farmers, food shortages were rare. (This, plus a more familiar climate, may help explain why life expectancy in Massachusetts was over 70 years, compared to under 50 in Virginia.) Finally, New England's very drawbacks—its stony soil and harsh winters—saved Massachusetts from two factors that kept life in Virginia unsettled: the continual influx of new immigrants and the emergence of large plantations that lent themselves to slave labor.

One more thing distinguished Massachusetts from Virginia. In Massachusetts, most settlers lived close together in towns. This could involve women in the petty conflicts of small-town life, but it also gave them regular opportunities to see friends, go to church, and exchange services with neighbors. In Virginia, where families generally lived on separate plantations, women spent much more of their time within the circle of their own households and had less opportunity to benefit from the conversation and support of other wives.

Women in the Northern Colonies

Between 1700 and 1780, the population of the American colonies increased more than tenfold, from 250,000 to nearly 3 million. Driving that increase were two important trends: soaring levels of immigrati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: BREAKING OLD TIES: AMERICAN WOMEN BEFORE 1800

- PART II: WOMEN'S PLACE IN AN EXPANDING NATION: 1800-1865

- PART III: SEEKING A VOICE: 1865-1914

- PART IV: TWO STEPS FORWARD, ONE STEP BACKWARD: 1914-1965

- PART V: REDEFINING WOMEN'S PLACE: 1965 TO THE PRESENT

- AMERICAN WOMEN: STATISTICS OVER TIME

- FURTHER READING

- INDEX

- MAP ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS