Introduction

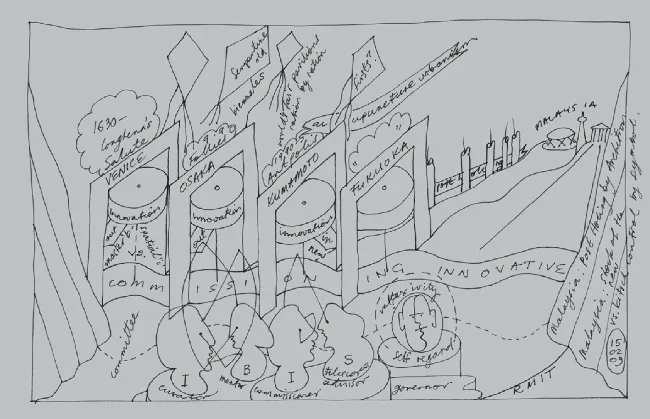

The practice of architecture has persisted in a recognisable mode for a very long time. The organisation of the office of Sir John Soane (1753–1837) is recognisable in ways in which architects work now: the digital revolution has made one of his key design development and marketing methods ubiquitous. Soane worked with two delineators, Joseph Gandy and George Basevi, and designs moved from drawing to model to delineation and back again in a manner that is evident in the office of savvy, computer-literate architects like ARM anywhere in the world today. Client attitudes to architects do not seem to have altered much in the West either. In 1630 the Venetian Parliament commissioned Santa Maria Della Salute.1 Seeking an outstanding design, they immediately began the search for an architect outside Venice, sending a delegation to Rome to interview the world-famous architects there. Why is this still so often where clients begin, assuming that their own culture is incapable of innovation? On their return, the building committee of the Parliament decided to run an international competition, and the outcome of that was a tie between two Venetian architects: one whose design solved the difficult ritual requirements of the proposed church, the other an architect noted for his technical capabilities in the area of securing marble to brickwork. Again we are shocked by the familiarity of this conundrum: a client choosing between spatial thinking and master building. Parliament met and resolved the deadlock in favour of innovation. The losing architect sued in the courts. That seems utterly current too.

Is this continuum with its deeply entrenched drivers only true in Europe and its former colonies? Or is it all pervading? Joseph Needham,2 who devoted much of his life to a scholarship that proved that China was often centuries ahead of the West in scientific discovery (snow crystals, six-sided symmetry of, 135 BC) and technical invention (ball bearings, second century BC; printed book, seventh century AD), was enormously impressed by the continuities in civil organisation in that country, but puzzled about why the leadership in scientific discovery and technical innovation ended in around 1500.3 Needham is not much interested in innovation in architecture, but he notes cast iron being used in the construction of pagodas (that still stand) in the fourth century BC, the invention by Li Chhun of the segmental arch bridge in AD 610 – many of his bridges still stand – and an early flood mitigation system of dams, sluice gates and water diversion canals from the third century BC is also still operating. Continuous development is his message, and then a mysterious hiatus.

Two kinds of continuity seem to pervade the history of architecture in East Asia:4 literal, as in the cast iron pagodas still existing; and phenomenal, as in the temples at Kyoto, which maintain their thirteenth-century AD form, but with regularly refreshed fabric. Five hundred years of stasis (or equilibrium – perhaps Chinese civil society foresaw the challenge to the planet wrought by unchecked development) makes for a history in architecture that celebrates the unchanging but also the location-free.5 Even as it does so, today China imports architectures from abroad and only recently has begun the building of a local culture of innovating architecture. Japan – early to jump onto the modern development bandwagon – has since World War II produced a formidably assured architectural culture,6 discernibly related to some ancient concerns – rawness is often cited. Japanese architects are – despite their ancient lineage – subject to the waves of ideas that flow through architectural thinking, and – as in the adoption of the Postmodern style by some – the culture succumbs at times to these rather unthinkingly. In the main, the consistency with which the culture adheres to recognisable traits makes it seem that there must be a commissioning class whose tastes are being satisfied by the carefully crafted buildings that appear every year. However, the visitor to Japan discovers that the jewels of the architectural culture are set in a vernacular of informal commercial and suburban building. Systematic patronage of architecture is in fact rare, and quality – as in the collective of all new art galleries, for example – seems to arise through unspoken competition between Prefectures and the institutions within them.

Twenty-first-century Chinese attempts at curating innovation have thus far set out to place new, imported exemplars

alongside ancient indigenous ones – as in the developer-led competitions to build houses by new and emerging architects adjacent to the Great Wall near Beijing.7 This is a pale reflection of the Weissenhof housing scheme in Stuttgart in 1927, which brought together designs that sought to showcase new ways of living, with at least a semblance of thought for mass housing. Only the emerging rich are in mind in the current icon-seeking collections. Singapore architect Mok Wei Wei describes design development on a house in a similar complex near a famous lake as being led by a discussion about ‘how the rich live’.8

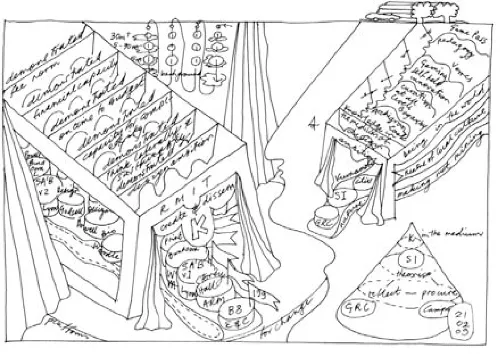

At RMIT in Australia, motivated by recognition of its geographical location and inspired by its ongoing attempts to shrug off its post-colonial cultural cringe, we began in the late 1980s an initiative that grew to systematically commission works from emerging innovative architects from Melbourne, Victoria – the city region in which our institution is based. This venture is described in the three following sections of the book. At the time, it seemed a lonely, almost defiant act.

Nevertheless, there was in Japan, in Kumamoto, at least one extraordinary example of a procurement process that can be seen to have played a very strong role in developing the innovative force of the local architectural culture. The Kumamoto process, known as the Artpolis (see below) commenced in 1988 after the Governor of the Prefecture had visited the IBA (a gathering in of designs by international stars) in Berlin in 1987. In contrast, it soon began to commission works from new and emerging Japanese, or Japan-domiciled, architects. The Artpolis became perhaps the most outstanding example of procuring innovative architecture while simultaneously building the local culture that East Asia has produced.

In South East Asia informal ways of building local cultures of innovative architecture were promoted by Ken Yeang (Asia Design Forum – ADF) and William Lim (AA Asia). Ken Yeang’s own Malaysian practice has been a raw collision between architecture for clients who look forward to new ways of living sustainably in the world, and the commissioning practices of a governing party determined to rule, and (following the dismissal of the then Deputy Premier) using architectural symbolism to bolster an Islamic nationalism.9 In 1999, the ADF culminated in bringing the brightest and best of a new generation of architects from East and West together in an urban design charette in Taipei; out of this came innovations in sustainable design that were applied by Yeang initially in Europe. AA Asia hit its stride with multidisciplinary conferences in Singapore in 2007 and 2008. In these – to the delight of the participants – the voice of the region is being found without the crutches of American or European critique. This is a fitting outcome for Lim’s efforts in theorising the specifics of the urban civilisation that is emerging in Asia.

The culture-building program of RMIT architecture has been deeply involved in both of these ventures (see p 32).10 Alumni of RMIT’s ‘invitational’ research program – Frank Ling and his partner in Architron, Pilar Gonzales Herreiz; and Richard Hassell and his partner in WOHA, Mun Summ Wong – have benefited from this combination of research into their own practice and a lively regional discourse. They have pioneered a newly self-aware practice mode in the region. Architron in Malaysia has built a portfolio of work that post-holes all of the housing types in that society, demonstrating the role of innovation across the board, and creating a contemporary version of the marketing strategy of the Vitruvius Brittanicus11 or the Oeuvres Complet.12 WOHA have been able to steer themselves into the space in Singapore that is crying out for innovative design as that city state seeks to reposition itself as a creative leader in the world. In the corporate sector, Andrew Lee Siew Meng and Jon Shinkfield have begun to adapt the RMIT approach to understanding design practice to the nurturing of design ‘ginger groups’ within their respective companies.

Continuities are undeniable, but we are prone to imagine that we, generation after generation, have invented the world we inhabit.13 This naïve assumption of originality, so prevalent in the twentieth century, is the enemy of creative innovation. What is emerging is a generation who have interrogated their intuition, surfaced its deep structures, contextualised its origins and begun to behave as conscious actors on the world stage.