eBook - ePub

Myth and the Greatest Generation

A Social History of Americans in World War II

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Myth and the Greatest Generation calls into question the glowing paradigm of the World War II generation set up by such books as The Greatest Generation by Tom Brokaw.

Including analysis of news reports, memoirs, novels, films and other cultural artefacts Ken Rose shows the war was much more disruptive to the lives of Americans in the military and on the home front during World War II than is generally acknowledged. Issues of racial, labor unrest, juvenile delinquency, and marital infidelity were rampant, and the black market flourished.

This book delves into both personal and national issues, calling into questions the dominant view of World War II as 'The Good War'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Myth and the Greatest Generation by Kenneth Rose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Americans Abroad

1

Fairness, Savagery, Delight, Trauma, and Vice

I. The Fair and the Savage

Americans fought two distinct wars between 1941 and 1945, wars separated not only by geography but also by the most basic assumptions of moral behavior. In terms of battlefield conduct, the war that Americans fought in Europe was not markedly different from the Napoleonic wars. But the war in the Pacific was revolutionary, a plunge into brutality and race hatred with seemingly no bottom. More than any other single factor, the differences between these two wars were rooted in the ways the enemies regarded each other.

In his memoir, Paul Fussell notes that “we always called the Germans ‘Krauts,’ doubtless to bolster our sense that we were killing creatures very odd and sinister and thus appropriate targets of contempt.”1 “Hun,” an appellation borrowed from World War I, was another derogatory word applied to Germans, and also in wide use was the almost affectionate-sounding “Jerry.” Robert Rasmus, who fought in Europe, remembered that he initially hated Germans both collectively and individually, but as increasing numbers of German dead came under his view, Rasmus had a revelation in which “each took on a personality. These were no longer an abstraction. These were no longer the Germans of the brutish faces and the helmets we saw in the newsreels. They were exactly our age. These were boys like us.”2 A soldier in Italy told Martha Gellhorn that he felt a similar kinship with German soldiers, “We’re not mad at anybody. Jerry’s in there just because he’s ordered, same as we are.”3 This was so common an attitude that the army worried that “identification with the enemy” was becoming a “liability.”4

Because of this feeling of commonality among Germans and Americans, there was widespread agreement that combat between them, with some exceptions (such as the operations of German SS units), was “fair.” German tank commander Hans von Luck described the fighting in North Africa as “merciless, but always fair.”5 German and American medics and doctors not only gave medical relief to each other’s troops but also sometimes performed operations side by side.6 Lieutenant Sidney Hoffman, a frontline doctor in Africa, noted that the Germans “ran their own ambulances right into no man’s land … we tried not to hit them.” Twelve American ambulances were destroyed by the Germans, but Hoffman was quick to add, “I think it was accidental. … They seemed to respect the Red Cross as we do.”7

Corporal John F. O’Neill, who was repatriated after a stay in German hospitals and prison camps, insisted that “German front-line soldiers are always gentlemen. The experiences of all our wounded have proven that.”8 In addition, both sides honored the surrender of enemy troops, and once former enemies became noncombatants, it was often the case that relations between them not only relaxed but even became remarkably cordial. J. Glenn Gray recalled one incident when Americans fighting in Italy took prisoner a group of Germans:

We stared at one another with a confused mixture of hostility and fear, all alike victims of ignorance. Suddenly I heard some of the prisoners humming a tune under their breath. Four who were a trained quartet and had contrived to be captured together started to sing. Within a few minutes, the transformation in the atmosphere of that stable was complete, and amusing, too, in retrospect. The rifles were put down, some of them within easy reach of the captives. Everybody clustered closer and began to hum the melodies. Cigarettes were offered to the prisoners, snapshots of loved ones were displayed, and fraternization proceeded at a rapid rate. When the commanding officer, just as new to combat as his men, arrived on the scene, he was speechless with fury and amazement.9

Undeniably, the doctrine of “fairness” between German and American troops was constantly being stretched and challenged. In Italy, Eric Sevareid came across the body of a German soldier and asked two American soldiers standing nearby what had happened. “Son of a bitch kept lagging behind the others when we brought them in. We got tired of hurrying him up all the time.” Sevareid found he was not shocked by this “deliberate murder,” “merely a little surprised.”10 But despite innumerable violations, “fairness” at least existed as an ideal between Americans and Germans. Elsewhere, warfare was conducted on a radically different premise. Germans and Russians fought each other on the Eastern Front with a savagery that was virtually unrestrained.11 In the Pacific, Americans and Japanese waged a war of primal hatred.12

The way the American public viewed the Japanese was consistently more negative than its view of Germans, which helps explain why there were no German “relocation” camps in the United States. Robert Redfield noted:

We distinguish Nazis from Germans. Not all Italians are followers of Mussolini. We know these things and recognize them. But the Japanese are all “Japs.” The Japanese, in the thinking of most of our people, are all one thing: a people fanatically devoted to the destruction of the United States—our enemies, all of them.13

More than anything else, it was a perceived difference of mind that American writers focused on in articles on the Japanese psyche. In Atlantic Monthly, for instance, Helen Mears described the Japanese as “repressed” both socially and intellectually, and explained that “the ruthlessness of his attacks is the energy of years of pent-up repressions.”14 A Life magazine article claimed that Japanese behavior during the war—“a cold-blooded ruthlessness” and a “stubborn fanaticism in the face of death”—was not a wartime anomaly but was deeply rooted in Japanese culture. As evidence, Life analyzed The 47 Ronin (“the most popular play in Japan”) and found a blood-soaked drama in which “the Japanese audience demands extreme realism in scenes of cruelty.”15

American depictions of the Japanese were uglier, more intense, and more personal than their portrayals of the Germans, and the Japanese were much more likely to be reduced to subhuman caricatures than the Germans.16 When Americans were asked in 1945, “Which people do you think are more cruel at heart—the Germans or the Japanese?” 82 percent responded that it was the Japanese. Gallup pollsters commented that “attitudes toward the German and Japanese people do not vary to any important extent by education levels in this country” and that all strata of society believed that “the Japanese people show instincts considerably less civilized than the German people.”17 The difference in the way Americans viewed their two enemies is made clear in the popular song “There’ll Be No Adolph Hitler nor Yellow Japs to Fear.”18

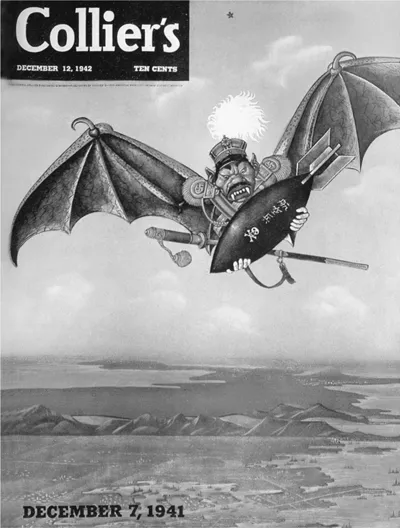

Racism is frequently offered up as the explanation for this difference, and undeniably there was a racial component to the fighting in the Pacific that was not found in Europe. In America, the ingrained Jim Crow system, the internment of resident Japanese, and the segregation and ill-treatment of black U.S. troops were all clear indications of the blithe assumptions of white racial superiority that prevailed in American society. When the fighting started, these assumptions were applied to the Japanese, whom in the popular imagery of the war were portrayed as rats, monkeys, cockroaches, snakes, dogs and bats.19 Senator Alben W. Barkley called the Japanese “brutes and beasts in the form of man.”20 One indication of the epithets that Americans were directing against the Japanese is found in the list released by the Office of War Information to radio broadcasters of words that were “recommended” and “not recommended” to describe the Japanese:

| Not Recommended | Recommended |

slimy Fiendish Bestial Grinning Toothy Monkey-man Jap-rat Yellow Inhuman Slant-eyes | Brutal Treacherous Cruel Tough Wanton Desperate Scheming Fanatical Venomous Ruthless21 |

Fig. 1.1 Collier’s cover by Arthur Szyk, 12 December 1942. (Reproduced with the cooperation of Alexandra Szyk Bracie and the Arthur Szyk Society.)

Even more xenophobic and racist than Americans were the Japanese. The Japanese took for granted their own racial superiority, and despite Japan’s promotion of a pan-Asianism and a “Co-Prosperity Sphere,” it soon became clear that these were concepts based not on cooperation among equals but on formulas for Japan’s subjugation of client nations. Japanese propaganda emphasized the purity and superiority of the Japanese race, which meant that the other degraded races of the world were fit only to obey and follow the Japanese. Nakajima Chikuhei, a Japanese industrialist and political leader, claimed that “it is the sacred duty of the leading race to lead and enlighten the inferior ones” and that Japan was “the sole superior race in the world.”22 This attitude would have grim repercussions for non-Japanese. Tamura Yoshio, a Japanese medical technician who infected human subjects with bacteriological agents (including bubonic plague, typhoid and syphilis) at Unit 731 in China, was asked in an interview if he had ever felt pity for his victims. He replied, “I had gotten to the point where I lacked pity. After all, we were already implanted with a narrow racism, in the form of a belief in the superiority of the so-called ‘Yamato Race.’ We disparaged all other races.”23

All of Asia would bear the brunt of this Japanese-style enlightenment, and as John W. Dower has noted, Japan’s “oppressive behavior toward other Asians earned the Japanese more hatred than support.”24 Certainly, the Chinese needed no reminders of the barbarity of the Japanese. China had already suffered one of the largest massacres in human history when Japanese soldiers put to death some 260,000 Chinese civilians in the Rape of Nanking.25 Rather than an incident in which the military got temporarily out of control, the Rape of Nanking lasted for seven weeks, with the Japanese exhibiting a wanton cruelty that exceeded even Nazi atrocities. Japanese soldiers held killing contests to see who was fastest at beheading prisoners, buried people alive (some were only partially buried, then run over by horses or tanks), nailed prisoners to trees and telephone poles and used them for bayonet practice, sprayed Chinese with gasoline and burned them alive, and were responsible for other Nanking residents being torn to pieces by dogs. In addition, this was one of the largest-scale rapes in human history, with some 20,000 to 80,000 victims. The Japanese went into a raping frenzy, violating women of all ages, from the youngest girl to the oldest woman. Often this was done in front of the women’s families, to make the rapes more satisfying to the Japanese.26 The peoples of other Asian nations under the yoke of the Japanese would soon have their own horror stories.

Some idea of the casual Japanese brutality toward native populations can be gleaned from a diary that was taken from the body of a dead Japanese artillery lieutenant in Burma. The lieutenant noted that natives were reluctant at first to become coolie laborers for the Japanese until “a first-class soldier, Hamauchi, a fellow graduate of mine at Arioki, took some to the edge of a ricefield, and the remainder saw that it was necessary to do as they were told.” Elsewhere, “the natives left behind did not show themselves but we had some fun pulling out some of the native girls.”27 Life editorialized in January 1942 that “the Japanese Army has spread across Asia a tale of horror that will be told for a thousand years,” and four months later the same magazine claimed that “the Japanese soldier is uncontrollable, shows no mercy and takes no prisoners. He is a fanatical, frenzied murderer.”28

Not surprisingly, the American hatred of the Japanese was mirrored by a Japanese contempt for their American enemies, who were portrayed as demons, devils, or beasts with tails.29 John Dower notes that in one Japanese drawing, Roosevelt and Churchill were rendered as “debauched ogres carousing with fellow demons in sight of Mount Fuji.”30 Even on the Eastern Front, the racial hatred was not as intense as it was in the Pacific.

The style of fighting practiced by the Japanese reflected both official military policy and societal norms. The 1908 Japanese army criminal code declared that “a commander who allows his unit to surrender to the enemy without fighting to the last man or who concedes a strategic area to the enemy shall be punishable by death.” The 1941 Japanese Field Service Code was even more blunt: “Do not be taken prisoner alive.”31 Japanese soldiers were trained to fight to the death for the glory of the emperor. To do so brought honor to the soldier and his family; to surrender brought shame to the soldier and humiliation to his family. One Japanese soldier explained that a Japanese who surrenders “commits dishonor. One must forget him completely. His wife and his poor mother and children erase him from their memories. There is no memorial placed for him. It is not that he is dead. It is that he never existed.”32 Not surprisingly, this attitude, coupled with intense racial hostility, made the fighting in the Pacific much less “conventional” than the war in Europe, and more frightening to most Americans. This unconventionality was reflected in very low Japanese surrender rates, with military units fighting to the death or committing suicide rather than suffering the disgrace of surrender. Said the U.S. general W. E. Lynd, “Japs do not leave any place they hold. They don’t go away. You just kill them.”33 Only a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was already speculation that suicide might be a national characteristic, that Japan was “committing national hara-kiri by throwing itself at the throat of its mightiest enemy.”34

From the beginning, American soldiers were astonished at the willingness of Japanese to sacrifice themselves by the hundreds in banzai suicide attacks that made no sense militarily. Fighting on the Bataan Peninsula in December 1941, Clayton Dahl of the 31st Infantry Regiment described Japanese attacks in his diary:

They’d come in waves, with their rifles high above their heads, screaming. God! What mass murder. They’d jump and stumble over the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- World War II Timeline

- Introduction

- Part I: Americans Abroad

- Part II: Americans at Home

- Part III: Americans and the Culture of World War II

- Part IV: Americans and the End of the War

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index