![]()

Part I

Violent conflict

![]()

1

Greed and grievance in civil war

With Anke Hoeffler

1.1 Introduction

Civil war is now far more common than international conflict: all of the 15 major armed conflicts listed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute for 2001 were internal (SIPRI, 2002).

In this chapter we develop an econometric model which predicts the outbreak of civil conflict. Analogous to the classic principles of murder detection, rebellion needs both motive and opportunity. The political science literature explains conflict in terms of motive: the circumstances in which people want to rebel are viewed as sufficiently rare to constitute the explanation. In Section 1.2 we contrast this with economic accounts which explain rebellion in terms of opportunity: it is the circumstances in which people are able to rebel that are rare. We discuss measurable variables which might enable us to test between the two accounts and present descriptive data on the 79 large civil conflicts that occurred between 1960 and 1999. In Section 1.3 we use econometric tests to discriminate between rival explanations and develop an integrated model which provides a synthesis. Section 1.4 presents a range of robustness checks and Section 1.5 discusses the results.

This analysis considerably extends and revises our earlier work (Collier and Hoeffler, 1998). In our previous theory, we assumed that rebel movements incurred net costs during conflict, so that post-conflict pay-offs would be decisive. The core of the paper was the derivation and testing of the implication that high post-conflict payoffs would tend to justify long civil wars. We now recognize that this assumption is untenable: rebel groups often more than cover their costs during the conflict. Here we propose a more general theory which juxtaposes the opportunities for rebellion against the constraints. Our previous empirical analysis conflated the initiation and the duration of rebellion. We now treat this separately. This paper focuses on the initiation of rebellion.1 Our sample is expanded from a cross-section analysis of 98 countries during the period 1960–92, to a comprehensive coverage of 750 five-year episodes over the period 1960–99, enabling us to analyse double the number of war starts. Further, we expand from four explanatory variables to a more extensive coverage of potential determinants, testing for robustness to select a preferred specification.

1.2 Rebellion: approaches and measures

1.2.1 Preferences, perceptions, and opportunities

Political science offers an account of conflict in terms of motive: rebellion occurs when grievances are sufficiently acute that people want to engage in violent protest. In marked contrast, a small economic theory literature, typified by Grossman (1991, 1999), models rebellion as an industry that generates profits from looting, so that ‘the insurgents are indistinguishable from bandits or pirates’ (Grossman, 1999, p. 269). Such rebellions are motivated by greed, which is presumably sufficiently common that profitable opportunities for rebellion will not be passed up.2 Hence, the incidence of rebellion is not explained by motive, but by the atypical circumstances that generate profitable opportunities. Thus, the political science and economic approaches to rebellion have assumed both different rebel motivation—grievance versus greed—and different explanations—atypical grievances versus atypical opportunities.

Hirshleifer (1995, 2001) provides an important refinement on the motive-opportunity dichotomy. He classifies the possible causes of conflict into preferences, opportunities, and perceptions. The introduction of perceptions allows for the possibility that both opportunities and grievances might be wrongly perceived. If the perceived opportunity for rebellion is illusory—analogous to the ‘winners’ curse’—unprofitability will cause collapse, perhaps before reaching our threshold for civil war. By contrast, when exaggerated grievances trigger rebellion, fighting does not dispel the misperception and indeed may generate genuine grievances.

Misperceptions of grievances may be very common: all societies may have groups with exaggerated grievances. In this case, as with greed-rebellion, motive would not explain the incidence of rebellion. Societies that experienced civil war would be distinguished by the atypical viability of rebellion. In such societies rebellions would be conducted by viable not-for-profit organizations, pursuing misperceived agendas by violent means.

Greed and misperceived grievance have important similarities as accounts of rebellion. They provide a common explanation—‘opportunity’ and ‘viability’ describe the common conditions sufficient for profit-seeking, or not-for-profit, rebel organizations to exist. On our evidence they are observationally equivalent since we cannot observe motives. They can jointly be contrasted with the political account of conflict in which the grievances that both motivate and explain rebellion are assumed to be well-grounded in objective circumstances such as unusually high inequality, or unusually weak political rights. We now turn to the proxies for opportunities and objective grievances.

1.2.2 Proxies for opportunity

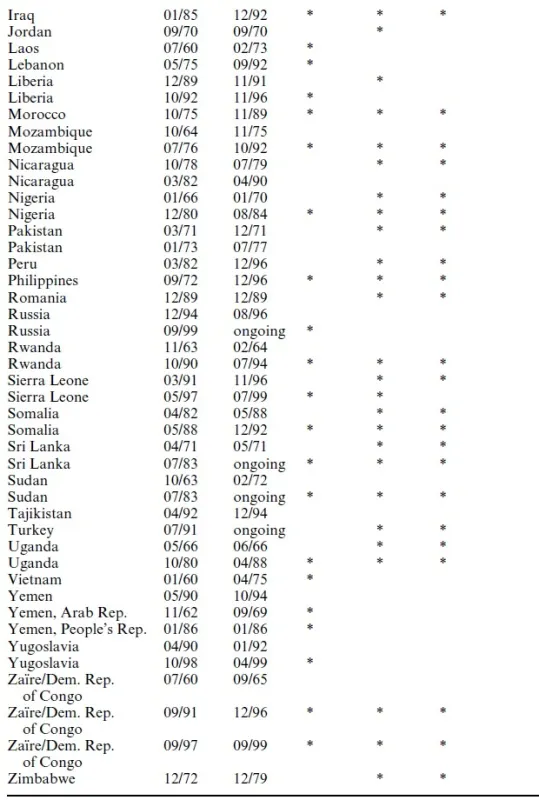

The first step in an empirical investigation of conflict is a clear and workable definition of the phenomenon. We define civil war as an internal conflict with at least 1,000 combat-related deaths per year. In order to distinguish wars from massacres, both government forces and an identifiable rebel organization must suffer at least 5 per cent of these fatalities. This definition has become standard following the seminal data collection of Small and Singer (1982) and Singer and Small (1994). We use an expanded and updated version of their data set that covers 161 countries over the period 1960–99 and identifies 79 civil wars, listed in Table 1.1. Our task is to explain the initiation of civil war using these data.3

Table 1.1 Outbreaks of war

Note: Previous wars include war starts 1945–94.

We now consider quantitative indicators of opportunity, starting with opportunities for financing rebellion. We consider three common sources: extortion of natural resources, donations from diasporas, and subventions from hostile governments.4

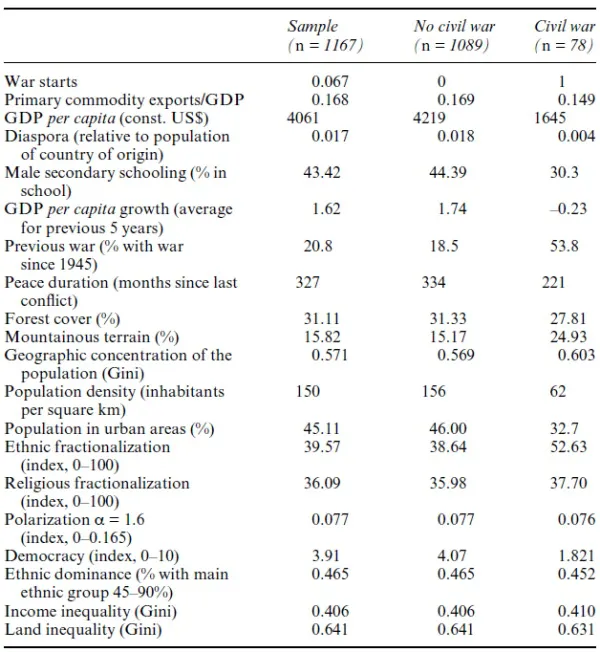

Klare (2001) provides a good discussion of natural resource extortion, such as diamonds in West Africa, timber in Cambodia, and cocaine in Colombia. In Table 1.2, we proxy natural resources by the ratio of primary commodity exports to GDP for each of the 161 countries. As with our other variables, we measure at intervals of five years, starting in 1960 and ending in 1995. We then consider the subsequent five years as an ‘episode’ and compare those in which a civil war broke out (‘conflict episodes’) with those that were conflict-free (‘peace episodes’). The descriptive statistics give little support to the opportunity thesis: the conflict episodes were on average slightly less dependent upon primary commodity exports than the peace episodes. However, there is a substantial difference in the dispersion. The peace episodes tended to have either markedly below-average or markedly above-average dependence, while the conflict episodes were grouped around the mean.5 Possibly if natural resources are sufficiently abundant, as in Saudi Arabia, the government may be so well-financed that rebellion is militarily infeasible. This offsetting effect may make the net effect of natural resources non-monotonic.6 The observed pattern may also reflect differences between primary commodities (which we defer to Section 1.3). Further, primary commodities are associated with other characteristics that may cause civil war, such as poor public service provision, corruption and economic mismanagement (Sachs and Warner, 2000). Potentially, any increase in conflict risk may be due to rebel responses to such poor governance rather than to financial opportunities.

Table 1.2 Descriptive statistics

Note: We examine 78—rather than the 79—war starts as listed in Table 2.1 because Pakistan experienced two outbreaks of war during 1970–74. We only include one of these war starts to avoid double counting.

A second source of rebel finance is from diasporas. Angoustures and Pascal (1996) review the evidence, an example being finance for the Tamil Tigers from Tamils in north America. We proxy the size of a country’s diaspora by its emigrants living in the US, as given in US Census data. Although this neglects diasporas living in other countries, it ensures uniformity in the aggregate: all diasporas are in the same legal, organizational, and economic environment. We then take this emigrant population as a proportion of the population in the country of origin. In the formal analysis we decompose the diaspora into that part induced by conflict and that which is exogenous to conflict, but here we simply consider the crude numbers. These do not support the opportunity thesis: diasporas are substantially smaller in the conflict episodes.

A third source of rebel finance is from hostile governments. For example, the government of Southern Rhodesia pump-primed the Renamo rebellion in Mozambique. Our proxy for the willingness of foreign governments to finance military opposition to the incumbent government is the Cold War. During the Cold War each great power supported rebellions in countries allied to the opposing power. There is some support for the opportunity thesis: only eleven of the 79 wars broke out during the 1990s.

We next consider opportunities arising from atypically low cost. Recruits must be paid, and their cost may be related to the income forgone by enlisting as a rebel. Rebellions may occur when foregone income is unusually low. Since non-economists regard this as fanciful we give the example of the Russian civil war. Reds and Whites, both rebel armies, had four million desertions (the obverse of the recruitment problem). The desertion rate was ten times higher in summer than in winter: the recruits being peasants, income foregone were much higher at harvest time (Figes, 1996). We try three proxies for foregone income: mean income per capita, male secondary schooling, and the growth rate of the economy. As shown in Table 1.2, the conflict episodes started from less than half the mean income of the peace episodes. However, so many characteristics are correlated with per capita income that, depending upon what other variables are included, the proxy is open to other interpretations. Our second proxy, male secondary school enrolment, has the advantage of being focused on young males—the group from whom rebels are recruited. The conflict episodes indeed started from lower school enrolment, but this is again open to alternative interpretation: education may affect...