![]()

Part 1

The Setting

![]()

1

Barack Obama

A Reagan of the Left?

Andrew J. Dowdle, Dirk C. van Raemdonck, and Robert Maranto

Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that, you know, Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not. He put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it. . . . I think it’s fair to say that the Republicans were the party of ideas for a pretty long chunk of time there over the last 10, 15 years, in the sense that they were challenging conventional wisdom.

—Barack Obama, quoted in “There You Go Again” 2008

Almost every new presidential administration surges into office promising a tide of change. Even when the incoming president belongs to the same party as his predecessor, priorities and faces typically change. During the most recent intraparty transition, George H. W. Bush replaced every cabinet secretary with more than a year’s service in the Reagan administration and promised a “kinder, gentler America” than that of his predecessor. Evaluating change requires determining the magnitude of the change as well as whether that change generates new policies that are or will be sustained and built upon by future presidents. Is the change so significant and lasting that it builds a new regime?

Obama: Change We Can Regime?

Like George W. Bush in 2000, Bill Clinton in 1992, and Ronald Reagan in 1980, Barack Obama sought to reshape government, to alter the existing political order. With the largest popular vote majority since 1988 and the largest by a Democratic candidate since 1964, large gains and a majority in the U.S. House, a filibuster-proof Senate majority, and entering office at a time of economic crisis and two simultaneous wars, President Obama was seemingly poised to become America’s first regime-constructing president since Ronald Reagan. Indeed, this was candidate Obama’s stated goal.

Using the work of Stephen Skowronek (1993, 1997), we analyze whether Obama will be able to establish a new political regime to replace the Republican presidential regime that has existed since 1980. Skowronek proposes a cyclical model of the presidency based on presidential regimes. Regimes exist when a new type of public philosophy is promoted by a “carrier” party that is able to gain political control and transform that philosophy into concrete policy measures. It is crucial that such regimes have a strong, popular leader in the White House to act as the face of these new measures. The success of the new regime is such that the subsequent political landscape is dominated by this new political philosophy and a new dominant political coalition such as the New Deal coalition. Subsequent administrations typically try to pass incremental initiatives designed to reform, not overturn, the measures put in place by the new regime.

Skowronek identifies five distinct political regimes in U.S. history associated with five “reconstructive” presidencies: Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, and Reagan. These presidents faced a long-standing political order dominated by the other political party. However, the old ideology had begun to become irrelevant. Old interests were losing power as society changed and new interests arose. Periods of disjunction at the end of an old regime come to a close when these presidents and their party present a new vision and are given a mandate by the electorate and the rest of the political system.

Reconstructive presidents are succeeded by one of the following: presidents of articulation, presidents of disjunction, and presidents of preemption. Presidents of articulation try to implement, adjust, and, in some cases, expand the political regimes founded by their reconstructive predecessors. George H. W. Bush and Harry Truman are good examples. Disjunctive presidents, in contrast, serve near the end of a political regime’s life span. They have the daunting task of balancing the constant demands of the coalition of interests at the heart of the regime against the growing public perception of regime irrelevance and illegitimacy. Such balancers include Carter and Pierce.

Preemptive presidents represent the dominant party’s opposition within the existing regime. These “opposition presidents” can still win elections under the existing order. However, they appear only in instances of significant division

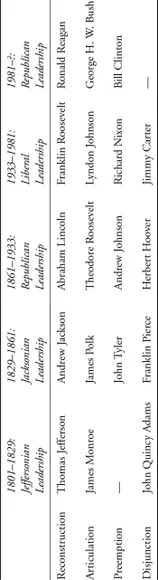

Table 1.1 Presidential Political Regimes in The United States

Source: Based on Skowronek (1993, 2008).

within the regime party, a non-ideological minority candidate (who takes advantage of a prominent military career, a centrist image, and/or being unknown), and where the minority party runs an “indirect campaign” that minimizes debate on core issues and focuses on subsidiary or transitory issues, like the Republican decision in 1952 to run on “Korea, Communism and Corruption,” instead of attacking the New Deal (Crockett 2008).

These criteria seem to argue against Obama being a mere electoral deviation within the existing order. Obama did not have a military career. While many Republicans were unhappy with John McCain, he did receive 90 percent of the Republican vote in the general election. Obama represented a clear rejection of the previous administration, even if he may, on occasion, have adopted a strategy of strategic ambiguity.

The 2008 presidential election put into place a new president whose regime affiliation seemed to be a clear repudiation of the fifth presidential regime inaugurated under Reagan. On the surface, this election was the strongest challenge to the old regime to date. From 1984 to 2008, Republicans clearly dominated presidential electoral politics. While Clinton won in 1992 and 1996, he never won a popular majority and avoided running on a mandate of sweeping change and a wholesale repudiation of the policies of his Republican predecessors. Not only did the Republican presidential nominee lose in 2008, but the party also lost many seats in the 2006 and 2008 elections. However, there is reason to question whether a new Obama regime might replace the Reagan regime or whether Obama, like Clinton, will bear the label of a preemptive president.

A New Regime?

With slogans such as “Change We Can Believe In” and “Yes, We Can!,” the incoming Obama administration seemed poised to make major alterations to existing policies and possibly create a new, sixth regime. Obama’s election also seemed to augur drastic change. While a majority of senior citizen voters cast their ballots for McCain, the one age cohort that Obama decisively won was voters below the age of thirty. Some scholars have argued that a new wave of voters provided the political fuel for the Roosevelt realignment (Andersen 1979), although Campbell (1985) argues that conversion of some former Republican voters played an important role as well.

These political winds appeared to open the door for change. A new party controlled the White House and, for a period of time, had the sixty seats in the U.S. Senate needed to prevent a filibuster. Parties are, by their nature, imperfect coalitions and often dueling aggregations of conflicting desires, but the prevailing wisdom was that the parties were more bifurcated at the elite level than at any time since the Great Depression (see Levendusky 2009). While some scholars have questioned the depth and breadth of these partisan divisions (Fiorina et al. 2004), others have argued that individuals in the active and even the mass public have internalized these partisan divisions (Jacobson 2007; Abramowitz 2010). Thus, Democratic elites and voters should have rallied behind a president willing to present a new agenda. They also should have been less willing to compromise with the minority Republicans because of this political polarization.

It is impossible to overstate what the election of Obama represented to many voters. Within the president’s own lifetime, African Americans have faced state-sanctioned barriers that limited their rights to vote, marry, attend school, travel, reside in areas of their choosing, and participate in other aspects of civic and personal life. Instead of protecting them, local and state governments often served as agents of discrimination, while the federal government stood by in apathy.

The incoming president also faced policy challenges that called for a deviation from the status quo. While the conflict in Iraq appeared to be winding down, the war in Afghanistan had taken a turn for the worse. A long laundry list of controversies (e.g. foreign reaction to the invasion of Iraq, allegations of torture and illegal detention at the Guantánamo Bay military base, the U.S. stance on the Kyoto protocols on climate change) had hurt the image of the United States worldwide. In fact, the overwhelming enthusiasm that Obama generated abroad was in anticipation that he would change the policies of the Bush administration. The campaign capitalized on this by staging the first address of his general election campaign in Berlin.

While Obama had expected to face a plethora of foreign policy challenges, the financial crash of late 2008 forced a number of unforeseen domestic decisions. In October, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 led to the creation of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which was left to the new Obama administration to implement. The financial crash led to calls for new measures of government oversight. The economic downturn became the Great Recession, which the incoming administration attempted to address with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, pumping $800 billion of stimulus into the economy.

Traditional Democratic constituencies also wanted changes in domestic policy. The first legislation the new president introduced was the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, a symbolic nod to feminist groups. Hate crime legislation was a high priority. The administration also proposed climate change legislation in September 2009. Health care reform, while aimed at specific constituencies, had been an aspiration of Democrats since the Truman administration. All of these policy proposals represented significant departures from the agenda and policy preferences of the previous administration. However, are they significant enough to warrant the label of a new regime and will these reforms not only last but manage to expand in depth and scope?

Or Just a Continuation of the Old?

While the Obama campaign was propelled by “change we can believe in,” the realities for the new administration were often quite different. Election night pundits might predict that partisan change triggers policy changes, but there are also reasons to believe that the likelihood and magnitude of reform that a new administration can bring are overstated. Structural, political, and policy constraints all place brakes upon a new agenda.

The power of these constraints means that existing political regimes are surprisingly resilient. As numerous scholars have argued, Americans have deeply contradictory views about their presidents (see Cronin and Genovese 2009). On the one hand, they want presidents who will change government and society. On the other hand, they do not want their presidents to become too powerful. Ingrained suspicion of centralized power, combined with constitutional constraints, makes it difficult for presidents to reshape government and society. Yet, by the nature of their office, presidents are drawn to do just that. For political regimes to collapse, there must be a sustained condition that delegitimizes the old system, such as the stagflation economy of the 1970s that paved the way for the Reagan regime.

Not every president who attempts a new regime will succeed. Skowronek gives the example of Bill Clinton as a preemptive president who was unable to significantly alter the current political regime. He began with an ambitious agenda, but the keystone of his legislative program, health care reform, failed and his party lost control of Congress in 1994 after having dominated the House for over forty years. Existing regimes are very resilient. Chastened, Clinton acquiesced in the Reagan regime for the sake of remaining in power and limited himself to policy changes that were either marginal or did not conflict with the existing regime.

What lessons does the preemptive case of Bill Clinton provide to help us understand the pitfalls facing the Obama presidency? One of the first maxims of American politics is that power is dispersed. Party change has less influence on public policy in those countries with “countermajoritarian institutional constraints” (Schmidt 1996, 155). Federalism and separation of powers both limit the ability of a new administration to impose its will on the political universe. As Weatherford (2002) points out, voters are only one part of political realignment. Other politicians and interest groups also have to reorient their behavior during the consolidation phase after the initial critical election.

Political parties are supposed to be the binding agent that overcomes the Madisonian institutional ambition that prevents cooperation among institutions (Schattschneider 1942). However, American political parties have been traditionally weak, because they lack the resources to reward support or punish deviance from the party agenda. Furthermore, a federal system of parties further weakens this potential centripetal force (Lipset 1990). As Madison might say, a decentralized system of parties coupled with Federalist Number 10’s factional heterogeneity in a large country may mean that policy coordination is difficult even if the barriers to institutional cooperation of Federalist Number 51 falter.

The Obama administration could appeal to the mass public for support. For most of his presidency, a plurality, if not at some time a strong majority, of poll respondents have approved of his presidency. As Edwards (2003) notes, though, success in the bully pulpit is rare. Moreover, drastic, wide-ranging policy change also represents the type of agenda most likely to draw opposition and least likely to succeed. The Obama administration’s choice of issues, such as health care reform, sparked heightened opposition. If Wildavsky’s (1966) two presidencies theory is still valid, the president should have the most success in foreign policy. The public’s growing disenchantment with Iraq made this an area where it would have been easier to pursue a change in policy. However, the administration has continued to pursue an incremental withdrawal.

Instead, domestic issues such as health care and climate change were chosen. These were likely to fall into the “political echo chamber,” where Rottinghaus (2010) warns that political success is difficult to achieve, as the experience of the Clinton administration demonstrated. While they may have been popular with groups inside the Democratic coalition, they were likely to generate opposition as well. They might represent attempts to change policy, but they were also less likely to be successful attempts.

Political party building might create a tool to mobilize support and unify the Democratic coalition to overcome these hurdles. Democratic presidents have been less successful at party building than their Republican counterparts (Galvin 2010). A task more likely to yield immediate benefit for the White House would be to build stronger relationships with interest groups sympathetic to the administration’s goals. The previous administration had made efforts to utilize this tactic with faith-based organizations and had managed to accomplish significant policy changes pleasing both to these groups and to the White House (Aberbach 2005). Organizing for America, an entity created by the Democratic National Committee to spur community organizing, did serve as a potential vehicle for mobilizing support for Obama’s programs. However, as former Dean for America (2004) presidential campaign staffer Zephyr Teachout predicted in January 2009, its success in mobilizing public support for Obama’s agenda has been underwhelming (Teachout 2009).

If the Obama team was unable to direct outside pressure on Congress, the White House could have elected to expand the administrative presidency to accomplish their goals. Barilleaux (1988) argues that the Reagan administration rebuilt presidential power in the post-Watergate era largely through the use of unilateral prerogative power. Both Presidents Bush also utilized the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within the Office of Management and Budget to increase presidential control over the bureaucracy. As West (2005) points out, though, Democratic presidents have been less likely to expand the role of OIRA since they perceive the bureaucracy to be less resistant to their proposals.

Political culture represents a less fluid element that serves as a brake on rapid and drastic change. In...