1 Life, career and politics

Overview

J.B. Priestley (1894–1984) was born into a lower-middle-class family in Bradford, England at the close of the nineteenth century. A playwright, novelist, essayist, broadcaster and socialist-humanist, he left school in his mid-teens, and went into the wool trade as a clerk. It was during this period, before his time on the Front in France during the First World War (1914–18), that he began a writing career which was to span almost a century, one in which much of the vast social and cultural change was reflected in the work he produced.

His career demonstrated a new thread of mobility in the classes from working and lower middle to middle-class professional which remained an unrealised dream in general but was supremely epitomised in his own life. So many phases in his development were representative of unfolding English history between the years 1894 and 1984.

(Brome 1988: 485)

John Boynton (or ‘Jack’) Priestley was one of the most prolific and versatile English writers of the twentieth century: he worked across journalism, criticism, literature, theatre, film and radio. He experienced varying levels of success in each medium, and rarely worked solely in any one field at any one time. A socialist at heart and in practice, he believed that the creative arts, both in terms of production and consumption, had a vital importance to society at large and to the individual in particular. Priestley was both a populist and an intellectual, a man of letters and a man of the people, and his plays remain popular and have retained a remarkable cultural currency in the present day. Although much critical reference is made to his written output in general, this volume focuses on Priestley the playwright, theatre theorist and practitioner; he wrote a great deal about theatre, the arts and cultural production, as well as writing over thirty works for the stage. Like Bertolt Brecht, he did not sit quietly in the darkened auditorium while others produced his work, nor did he rely on others to find theatres in which to produce it. Throughout his theatre career, he was a proactive playwright, setting up a production company, keeping a close eye on critical debates and trying to find ways in which he could push the possibilities of playwriting as a creative art into new frontiers and forms. Others have also seen a parallel with Brecht.

I see him … as in one way to be bracketed with Noël Coward. He’s prolific, his plays work, they generally only have one set and a reasonable size of cast … He’s practical, he’s a man of the theatre. But in another sense he can justly be compared with Brecht, he goes as deep … when one realizes what his plays are really about, then one perceives that he is just as big as Brecht, that his themes have huge sweep and grandeur.

(Braine 1978: 141)

Although a socialist by conviction, Priestley did not share Brecht’s Marxist leanings, but was equally not a ‘party’ man. He was influenced by developments in scientific and political thinking as well as by Jungian psychology: his processing of these developments filtered through into his plays as well as his theories of theatre, drama and the social function of the arts.

The analysis of Priestley’s contribution to British theatre generally and playwriting in particular remains somewhat bound to the received critical and historical framing of British theatre between the two world wars and into the early 1950s. Here, dominant historical narratives focus on subsidised theatres and on 1956 and John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger as a perceived turning point in the development of drama in Britain. Although challenged by a number of recent theatre histories (see Gale 1996; Luckhurst 2006; Rebellato 1999), such narratives privilege the marginal avant-garde and the non-commercial sections of the industry: such ‘longstanding … prejudices’, which hark back to the nineteenth century binary oppositions of the legitimate and the non-legitimate theatre, mean that other key periods and kinds of work remain unexamined (see Savran 2004). The context in which Priestley worked was that of a commercial theatre industry, differing in essence from its European counterparts in its complete lack of government subsidy. J.B. Priestley fought this system, through the ways in which he operated as a playwright and a producer, but it provided the economic background to his theatre career. Some theatre histories of the period (see Chothia 1996; Davies 1987) would have us believe that there was nothing of worth being produced in the commercial West End during the interwar years (1918–39), the period which saw Priestley’s debut works in production. Others, however, have pointed to the breadth and depth of plays produced and to the fact that the commercial production system relied on cross-fertilisation from all areas of the ‘theatre world’ – including the independent, club and subscription theatres (Barker and Gale 2000; Kershaw 2004). Thus, a reappraisal of Priestley’s practice in the theatre requires a close examination of the context in which that work took place.

This volume offers a re-evaluation of Priestley’s theatre writing from a number of perspectives. Part I provides an overview of the political and ideological beliefs which drove his work, as well as a documentation and analysis of his theories of theatre and drama, his critique of the critics and his vision of the function of theatre as a form of cultural production. For Priestley theatre helped to define culture, in a society which was undergoing radical and swift social and economic transformation. In Part II, his major plays are grouped thematically and are discussed both in terms of their original production and reception and in terms of the ensuing critical analyses by academics and theatre historians. Finally, Part III focuses on a range of productions of three of his works, The Good Companions (1931), An Inspector Calls (1946) and Johnson Over Jordan (1939). Important materials from major theatre archives, as well as evidence from biographies, autobiographies, interviews and critical works are brought to bear on this re-evaluation of J.B. Priestley, one of the most popular, prolific, and often experimental, British playwrights of the twentieth century.1

Life and career: from Bradford to the West End

There are a number of biographies of J.B. Priestley, all of which offer a different focus in terms of their construction of a picture of Priestley’s life (Brome 1988; Cook 1997; Cooper 1970). Many of them borrow heavily from Priestley’s own autobiographical writing (Priestley 1940, 1941a, 1962, 1977), often without, however, attempting to authenticate or reflect upon the ways in which Priestley wrote about himself. Similarly many of the biographies fail to identify or challenge the various social, political and academic prejudices which have historically underpinned readings of his work. This part of the book uses the broad framework of these collective ‘depictions of a life’ as a means of charting the interrelationship between his life, career and ideological thinking. The son of a school teacher in the northern industrial community of Bradford, and a student of literature studying on an officer’s scholarship at the University of Cambridge immediately after the First World War, his origins influenced the development of his political thinking and in turn filtered into every aspect of his career in theatre.

after the war I turned away from politics, not because my political sympathies had changed but because I felt I needed a private world of a few friends and a lot of books . . . I became the typical Englishman behind his high wall and closed door . . .

Oddly enough it was not politics but the Theatre that opened the door and broke down the wall for me. In the early Thirties I turned from novels and essays to plays, and it happened that from the first I took more interest in the actual production of my plays than the average playwright does … I found myself at last leaving the quiet study … for the bustle and confusion and the concerted effort of theatrical production. … There might be more heartbreaks in the production of a play than in the publication of a book, but there was also much more fun. And something too that was more than fun – a sense of kinship with my fellow workers in the Theatre.

(Letter to a Returning Serviceman, Priestley 1945b: 27)

J.B. Priestley’s professional work in the theatre began in the early 1930s, and as he suggests in his Letter to a Returning Serviceman (1945), this new career pathway led him to a different, more collective way of working. Biographers and critics vary as to the degree to which they investigate Priestley’s theatre work: some focus on his plays more than others (Atkins 1981; Braine 1978; Evans 1964). There is, however, an overall acknowledgement that Priestley’s theatre work was central to his career from the early 1930s through to the late 1950s. Equally, theatre features in a great deal of his fictional writing, in novels such as The Good Companions (1929), Jenny Villiers (1947) and Lost Empires (1965); later in life he used theatre as a metaphor for modes of self-reflection and the processing of internal dialogue.

We carry a theatre around with us, and we should enjoy the comedy inside. What goes on in our inner world can soon be turned into an enjoyable comedy if we stop hugging and petting our injured vanity, our jealousy and envy.

(Priestley 1972: 32–3)

Here, late in life, Priestley is referring to the mediation of public and private selves, a process with which he was familiar and one that is vital in the biographical works of which he is the subject. Thus Vincent Brome is rather scathing about a great deal of Priestley’s writing (Brome 1988), but focuses very heavily on Priestley’s private relationships with women; his three wives, his supposed mistresses, and on his relationships with his children. Judith Cook, emphasising empirical social and historical research, gives a more balanced, detailed and contextualised analysis of Priestley’s life. She stresses the early influences of his childhood community and his years spent in action in France during the First World War (Cook 1997). Doubtless, these years, from September 1914 where he witnessed the atrocities of the war as a soldier in the trenches, to March 1919, when he left the army, hugely influenced Priestley’s writing life. Yet a number of critics have pointed to the fact that Priestley himself wrote relatively little about his war experience (Atkins 1981; Cooper 1970). He did not find in war ‘the deeper reality we all look for’; it did not transform him into an artist in the way it did others of his generation (Priestley 1962: 87).

When I look back on my life … these four-and-a-half years shrink at once; they seem nothing more than a queer bend in the road full of dust and confusion. But when memory really goes to work and I re-enter those years, then just because they used up all my earlier twenties … they suddenly turn into a whole epoch, almost another life in another world … I think the First War cut deeper and played more tricks with time because it was first, because it was bloodier, because it came out of a blue that nobody saw after 1914. The map that came to pieces in 1939 was never the apparently solid arrangement that blew up in 1914.

(Priestley 1962: 86)

For Priestley, dramatic representations of the 1914–18 war, relatively late to arrive on the interwar West End stages (see Barker and Gale 2000), such as R. C. Sherriff’s play Journey’s End (1928), presented trench life as ‘dry and commodious’ rather like a ‘suite in some Grand Hotel’ (Priestley 1962: 99–100). Priestley’s war finds its way into his writing through a continual return to the pre-1914 period, and through his sustained effort to encourage a process of self reflection in terms of our responsibilities as members of a community both nationally and internationally, rather than in overt and detailed accounts of his own actual war experience. His political views were sharpened and clarified, first by his war experience, and second through his time as a student in the early 1920s at Cambridge, which, much like Oxford, was still the enclave of the upper-middle and ruling classes. Here Priestley, whose promotion to the officer class had brought with it the possibility of a university grant, largely studied among younger men, from a very different class, predominantly from the south of England and educated in the private sector. Again, he does not write much about these years, during which he married, became a father and graduated. Later in life, however, he was very sceptical of certain types of Leavisite academic criticism which he saw as delimiting the boundaries of the purpose and function of literature, something which will be expanded upon later.

Following his degree, he turned down the offer of academic employment and began what was to become a long career as an essayist, journalist and critic. The success of his novel The Good Companions in 1929 afforded him financial stability and the possibility of creative experiment. By the early 1930s he began writing for theatre; his first play was an adaptation of The Good Companions (1931) written with Edward Knoblock. The second was Dangerous Corner (1932), which the celebrated author and critic Rebecca West (see Stokes 1996) thought contained ‘real dialogue with proper nerves in the sentences’. West congratulated him for having written so ‘rigorous and exciting’ a play, one which ‘refreshed … after the chopped hay of the ordinary English play’.2 Although seen by some as a relative failure in terms of its original West End production run (Brome 1988; Cook 1997), Dangerous Corner became one of Priestley’s most performed plays. His next play, Laburnum Grove (1933), originally ran for over 300 performances.

During the twenty-two years which cover the interwar period, London productions of plays rarely ran for more than 100 performances. Although occasionally there are years when the figure for productions lasting for 100 performances or more is as high as 46 per cent, the average figure is much lower at between 11 and 30 per cent. Unusually then, twelve of Priestley’s plays ran for more than 100 performances, and eight of these for more than 200 during their first West End production runs. There is no consistency in the ‘types’ of plays which proved most popular; The Good Companions (1931), Laburnum Grove (1933), Time and the Conways (1937), I Have Been Here Before (1937), When We Are Married (1938), They Came to a City (1943), How Are They at Home? (1944), Ever Since Paradise (1947) and The Linden Tree (1947) reveal often radically different approaches to dramatic writing. Priestley succeeded with comedy as much as with ‘plays of ideas’ and social observation. He consistently found audiences from the 1930s onwards. He would often have more than one play running in the West End at any one time, as well as simultaneous productions in continental Europe or in North America. Equally, his work continues to receive revivals all over the world in both professional and amateur contexts; the most recent and extraordinary example of this was British director Stephen Daldry’s National Theatre production of An Inspector Calls (1946) in 1992, which transferred from the subsidised sector into the West End, saw numerous international productions and was still touring England in 2005 (see Chapter 7). Very few other English playwrights could match his popularity during his heyday and fewer still have managed to sustain their cultural currency with audiences so consistently.

Life and career: from the West End to the post Second World War years

It is important to stress that Priestley continued with his other writing while working in the theatre. From the 1930s through to the early 1950s he produced more than fifteen novels, critical and autobiographical works. It is inappropriate to talk of Priestley’s career in the singular: by contemporary standards he had at least three careers running simultaneously. His autobiographical works all give evidence of an almost workaholic attitude to his professional life. He wrote to a regular schedule, and his life was shaped around his work. By the early 1930s he was well into his second marriage to Jane Wyndham Lewis (née Bannerman) and father to five children, adoptive father to one (Cook 1997). By the 1940s he was also working in radio and film and had gained a public celebrity status which he found somewhat intrusive as his circle of fans grew wider and ever more quick to recognise him in public places.

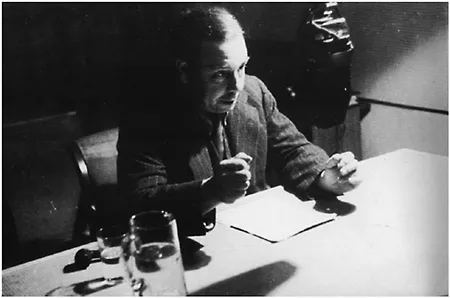

Figure 1 J.B. Priestley: wartime broadcasting for the BBC.

Priestley’s wartime radio broadcasts, known as the Sunday night ‘Postscripts’, brought his voice into the homes of all classes of British people. For a wartime audience he became a new kind of ‘radio personality’: the ‘first non-politician to whom listeners regularly tuned to hear his personal political and philosophical views’ (Nicholas 1995: 248). Begun in early 1940, his broadcasts stopped at his own request and then came back on air during 1941 only to be taken off again by both the BBC and the Ministry of Information, neither of whom would admit responsibility for doing so. Priestley himself suggests that as their political content became more overt, with frequent references to the politics of post-war reconstruction, the broadcasts became too controversial (Priestley 1967a: xix). The public, however, showed great support for his radio work as did other writers; Rebecca West wrote to thank him for them and for Storm Jameson, writer and journalist, they were ‘far and away the best’; she also suggested that in them he found ‘the poetry of the English’.3 For others, Priestley’s wartime radio broadcasts – the ‘Postscripts’ and those for the BBC Overseas Service – had an ambassadorial quality: the high-profile politician Ernest Bevin suggested ‘you have put over, in your own most effective and individual way, what we are trying to do here and, for this, the whole country owes you a debt of gratitude’.4 Those with political leanings to the right did not appreciate the growing level of dissent in Priestley’s broadcasts, but for many, in a war-torn England which relied on the radio for news and to some extent for comfort, they represented the ‘voice of the people’. Some even suggest that he ‘brought the BBC’s established traditions of impartiality and anonymity into conflict with its new needs: personality and mass appeal’ (Nicholas 1995: 266).

Life: a man through the eyes of others

Priestley had homes in London, on the Isle of Wight and later in Stratford-upon-Avon; from each he worked, entertained and travelled. His homes were often full of guests – writers, theatre people and other friends. Priestley worked and socialised with many of the key figures from all aspects of the British arts scene from the 1920s onwards, although few of these were from the so-called elitist sections of the ‘hig...