![]()

Part One

Group Therapy Essentials

![]()

Chapter One

An Introduction to Cognitive-Behavior Group Therapy with Youth

Jessica L. Stewart, Ray W. Christner, & Arthur Freeman

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) with youth clients has received considerable attention and support over the past several years for a variety of presenting problems experienced by youth, including depression, anxiety, anger and aggression, eating disorders, and such (Ollendick & King, 2004). With the growing interest in CBT among practitioners, a number of experts in the field have compiled thorough and useful resources for implementing CBT with child and adolescent clients (see Kendall, 2000; Reinecke, Dattilio, & Freeman, 2003). Not only has CBT been applied to a variety of presenting problems experienced by youth, but also there is growing implementation of CBT interventions in a variety of settings in which youth interact. Recently, Mennuti, Freeman, and Christner (2006) offered a resource specifically for addressing child and adolescent issues a school setting.

The focus for a number of the CBT resources for youth clients, however, is mostly on individual psychotherapy or intervention; yet, many professionals in the field are being faced with greater time constraints and increasing numbers of referrals. For this reason, therapists are looking for alternative and time efficient ways to work with youth. Freeman, Pretzer, Fleming, and Simon (2004) suggest that cognitive-behavior group therapy (CBGT) can be a natural alternative, or in some cases, a supplement to individual treatment. To date, there is a growing evidence-base for CBGT, as it has shown positive outcomes with youth for a variety of issues, including anger and aggression (Feindler & Ecton, 1986; Larson & Lochman, 2002), depression (Clarke, Rohde, Lewinsohn, Hops, & Seeley, 1999), and anxiety (Albano & Barlow, 1996; Flannery-Schroeder & Kendall, 2000; Ginsburg, Silverman, & Kurtines, 1995). Others have contributed excellent practical resources (Dryden & Neenan, 2002; Rose, 1998). Given the opportunities that CBGT offers for clinicians in a number of settings, it is only fitting that a comprehensive resource be available.

Our goal when deciding to develop this handbook was to fill the void for a comprehensive resource that presents not only the theoretical constructs of CBT and group therapy, but also to capture the innovative practices of CBGT with various presenting problems and in specific settings. As such, we hope this volume offers a complete guide designed to provide professionals working with youth a focused and structured model of group intervention, guided by cognitive-behavior theory, principles, and strategies. Whether experienced in CBT or new to the model, each chapter provides a basic review of the components of CBT relevant to the treatment being discussed and direction on how to apply them effectively in group therapy with youth. However, we encourage readers to also consult the already existing guides that present many of the essential tenets of using CBT with children and adolescents (see Friedberg & McClure, 2002; Reinecke, et al., 2003).

Brief History of the Group Modality

The modern form of group psychotherapy was pioneered by Joseph H. Pratt in the 20th century in the United States (Dreikurs & Corsini, 1954). On July 1, 1905, Pratt used group education to treat groups of patients with tuberculosis. The original intent of this approach was to expedite educating his patients on their condition of pulmonary tuberculosis. He quickly realized, however, the psychological benefits this approach demonstrated with his patients and proceeded to generalize this approach to other medical populations. Pratt later went on to work with psychiatric patients where he began to focus more on the emotional responses to their illnesses and the impact the illness had on the patients’ psychological condition. This occurred in the group setting and eventually became one of the staples to Pratt’s work in therapy (Pratt, 1945; Blatner, 1988). Although Pratt was most likely unaware at that time, he had created a methodical approach to the use of groups as a treatment modality.

Between 1908 and 1911, not long after Pratt began utilizing group methods, Jacob Moreno implemented the idea of creative drama with children in Vienna. This was among the first group methods implemented that did not focus on the concepts of individual therapy (Dreikurs & Corsini, 1954). Creative drama has become a valuable vehicle for teaching social skills, self expression, and ways of learning to groups of children. Compiling his insights from this process, in 1912 Moreno began the first known self-help group. He gathered together a group of prostitutes in Vienna to discuss their concerns, health issues, and life problems. During this group process, Moreno expected that each woman would become the therapeutic agent for the other women by sharing stories and experiences to which each woman could relate. These groups brought about a sense of community, of self-awareness, and an enhanced ability to solve problems. Moreno later applied the process of group psychotherapy to working with inmates in the prison system, focusing on the interaction between group members with less emphasis on education. In presenting this work at the American Psychiatric Association conference in Philadelphia in 1932, Moreno used the terms “group therapy” and “group psychotherapy” for the first time.

Group Therapy with Children

Alfred Adler was most likely the first psychiatrist to use the group method in an orderly and prescribed way in his child guidance clinics (Dreikurs & Corsini, 1954). In 1921, Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs engaged in the first family oriented group work which consisted of counseling and case planning for children and their families. Adler’s early work, consistent with his social philosophy, consisted of service within the poorer sections of Vienna, focusing on children in schools. He believed that “people are understood best in relation to their social environment” (Sweeney, 1999, p. 427), and therefore established child and family education centers where Adlerians worked with children, their parents in child-rearing groups, and marriage discussion groups. This work carried over to the United States when Dreikurs established these services in Chicago.

In 1934, Slavson initiated a shift from group therapy with adults to group therapy with children. At his child guidance clinic, he worked with groups of children to provide them with a myriad of tools for creativity. As a psychoanalyst, his group work consisted of goals similar to individual therapy that included the resolution of unconscious conflict that was blocking the function and productivity of the children in home and school settings. Slavson had two foci in his work. The first was on the group treatment of children who were judged as disturbed. A second focus was to work with parents of troubled children in what he termed child-focused group treatment of adults. In 1943, Slavson introduced the idea of activity group therapy (AGT) for children in The Introduction to Group Therapy (1943), and addressed the importance of understanding child development because of the constant change and growth. He believed that it was important to address the differences among age and developmental trends in childhood in play therapy, particularly when using play therapy in a group setting. He believed that children will have the greatest benefit from participating in a group with peers who have skills which fall within their own realm of understanding and by being challenged in a way that will allow a child to be successful. Other early group work with children includes Lauretta Bender’s use of play therapy groups for emotionally disturbed children at Bellevue hospital (Bender, 1937, Blatner, 1988).

“Certain problems, especially involving social skills, empathy, and interaction problems are best dealt with in a group setting. Groups are also used to facilitate discussion, to provide support, to normalize disorders, and to motivate otherwise disinterested children” (Kronenberger & Meyer, 2001, p. 34). By putting children together in a group they can see that their behaviors, feelings, thoughts, and families, are not strange or “weird.” It also allows children to see the impact of their behavior on other children. Whether or not this will add to their insight, help them change what they do, or effect a change on their out-of-group behavior is unclear. Yet, it is the contention of an ever-growing body of literature, and the authors and editors of this volume, that such a process is a viable and effective option for improving the service delivery of psychological services to children and adolescents.

Benefits and Cautions of Cognitive-Behavior Group Therapy

Group treatments can have a number of distinct advantages for clinicians, as well as clients. However, clinicians must use their judgment in determining the appropriateness of group intervention for particular clients, as it is not always the treatment of choice. We offer several thoughts for clinicians to consider when deciding to provide CBGT services. Some of these highlight the inherent benefits, while others draw attention to particular cautions.

Convenience

A primary benefit of the group modality is simply the capability to reach a large number of children and adolescents at one time. For some professionals, this has become a primary modality as a matter of necessity, based on healthcare limitations and restrictions on resources, rather than a desire to work with groups of clients. Yet for other clinicians, group interventions afford them the ability to deliver therapy to multiple clients within a limited timeframe, thus maximizing efficiency while not compromising effectiveness. While this is convenient from time, space, staffing, and financial standpoints, groups also (and more importantly) allow clinicians to begin seeing clients sooner to prevent the increase in difficulties or the decline in coping that may arise during a long wait period (Freeman et al., 2004). This issue of convenience can also have some disadvantages, as well. For instance, although clinicians may be able to see individuals in group sooner, it also means that there will be less time devoted to each individual client.

Ongoing Assessment

Many child and adolescent patients who present for therapy do so because of difficulties interacting with others. This may manifest for some through social anxiety, while for others may relate to being disrupting or disturbing, as is the case with children with anger problems or difficulty with behavioral inhibition. In individual therapy, it is difficult to see patients demonstrate skills with others and more challenging to facilitate the generalization of skills outside of the therapeutic setting. Goldstein and Goldstein (1998) suggest that interventions must occur in a setting in close proximity to where the problem occurs. In this case, a group format offers an ideal way for clinicians to directly observe participants’ emotional and behavioral reactions and interactions with peers. This affords valuable information regarding members’ repertoire of interpersonal responses and skills (e.g., decision making, coping, problem solving, communication), as well as their abilities to implement them successfully. Clinicians can use this information to refine their ongoing conceptualization of the client, as well as to monitor his or her progress. For children or adolescents with social problems, monitoring can occur with specific skills (e.g., listening to others when they are talking, making eye contact) by establishing a baseline during the initial one or two group sessions and then collecting data on the skills through observations. This information can be tracked and compared to baseline data over the course of the group treatment.

Psychoeducation

Groups also provide an increased emphasis on psychoeducation, which facilitates skills acquisition. This is a primary premise to providing psychotherapy to children and adolescents—that is, educating them about specific skills they can apply to their daily life in order to deal with their presenting problem. It is implausible to expect children and adolescents to apply skills that they have not yet mastered, or in some case have not yet learned. Thus, group interventions often begin by simple teaching of the skills necessary to remediate deficits or just to refine their existing skills for effectiveness.

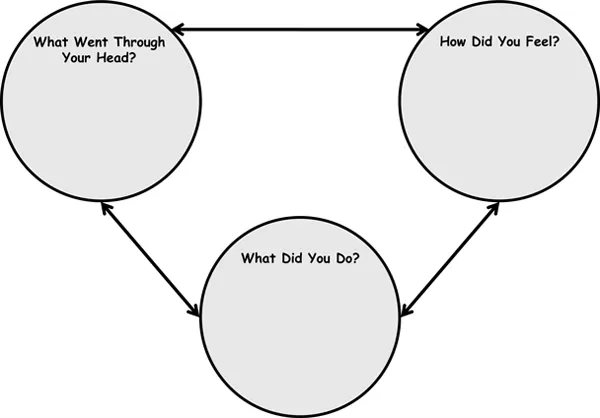

In addition to building skills, it is important when conducting CBGT to orient the children or adolescents to the CBT model (described in further detail below)—teaching them to recognize that a relationship exists between situations, beliefs, emotions, and behaviors. Subsequently, sessions will involve exercises used to modify their thoughts and acquire skills. We suggest that when socializing children and adolescents to the cognitive-behavioral connections, it is best to begin by using generic situations, different from their own, albeit situations they understand. For instance, with younger children we use stick figure drawings of common situations, such as a child holding a present, playing with a dog or cat, or swinging on a swing, with an empty thought bubble to demonstrate how changing thoughts may change feelings and behaviors. Friedberg and McClure (2002) explain a similar procedure in their book, Clinical Practice of Cognitive Therapy with Children and Adolescents: The Nuts and Bolts. For adolescents, while the pictures can be used, we often use a diagram demonstrating the interaction and select common scenes for the adolescents to discuss (e.g., talking on the phone, shopping at the mall, playing a sport). Figure 1.1 is an illustration of the diagram used.

Figure 1.1 Thought-Feeling-Behavior Connection. (© 2004 R. W. Christner. This form can be copied for clinical use. All other situations, please contact the author.)

Another area in which psychoeducation is useful is to expose the clients to facts and basic information regarding their diagnosis, symptoms, or experiences that have led to inclusion in group therapy. Many group programs include the presentation of written materials or working folders or notebooks at the start of group for the development of skills in an orderly sequence.

Social Comparison and Support

According to Festinger’s (1954) social comparison theory, change is internally motivated and occurs more readily when relevant others are available for social comparison, particularly in the presence of an ambiguous situation. The situations that typically produce the emotional and behavioral disturbances for young people are oftentimes new and ambiguous to them, as they are largely unaware of their mental processes (Reneicke, et al., 2003). Observing and hearing others who are similar to them, in terms of presenting problems or circumstances, affords group members reference points to offer information and increase motivation to adapt to their challenges and difficulties, as well as to help normalize what makes members feel “different” or alone. Yalom (2005) offered that “normalizing behavior” promotes a sense of universality that is one of the most helpful features of group therapy. It is common, especially in working with adolescents, for patients to discount the therapist’s ability to understand what they are “going through.” However, the group setting makes it less feasible for members to dismiss the observations of others who share similar problems.

In general, this is a significant benefit to group interventions, though for some youth, there can be a negative impact. We recall a 10-year-old boy in group who became very discouraged because he did not see himself as making similar gains as his groupmates, though his progress was commendable on an individual level. For him, this reinforced his thought, “I’m a failure.” To overcome this, we recommend setting specific goals for each child and having a target that they should meet for themselves. This requires celebrating the moments that each client achieves the steps leading to his or her goal.

Natural Laboratory

As noted earlier, group therapy settings offer a unique opportunity for clients to interact and practice skills in a safe setting. In essence, the group therapy setting serves as a natural laboratory in which members can “test out” their beliefs, as well as newly acquired strategies and interventions they have learned during the skill acquisition phase. This skill implementation aspect of group therapy offers an environmen...