![]()

Chapter 1

Review of Complementary and Alternative Modalities

This work uses a modification of the five domains created by the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM). CAM practitioners from around the United States worked with government officials and other medical personnel to create these classifications during the Clinton administration. These original classifications or domains have been slightly modified here to enable them to incorporate education, licensing, and regulation needs for CAM. Specifically, some “energy” therapies have been moved to the “biologically based” classification, including magnetic therapy, since magnetic fields are both detectable and measurable, and their effects can be measured in reasonable randomized trials overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The “Energy” domain has been updated to include “Metaphysical” as part of the title. This energy/metaphysical domain removes prayer from the mind/ body category as an “undetectable” (at least not detectable without much argument) means of intervention: prayer asks an outside, metaphysical force to intervene. The energy/metaphysical category now includes Reiki, shamanism, and therapeutic touch, not due to a lack of conventional scientific proof but because it will be recommended here that licensing and regulation for such modalities be classified in the same way that religious and faith-based means of intervention have always been classified, and that is to be exempt from such constraints.

The modalities discussed in this chapter are by no means exhaustive. This underscores one of the public problems with CAM—so many new interventions seem to appear every day. Despite the possibility that some of these interventions might become established as highly effective for the treatment of various conditions, this flux of modalities adds to the appearance of faddishness of CAM to both consumers and current health professionals. Where the expression “drug of the week” refers to the rapid development and release of new medications in the United States, so does a CAM “modality of the week” reflect this proliferation of new methods. This is more likely due to the nature of our “try and discard” culture than to anything good for health care. It would therefore be useful to adopt a five-domain classification system, so one can quickly refer to a modality as falling within an easily understood classification or type.

Part of the purpose of this chapter is to offer some information about scientific studies done for CAM modalities to assist prospective clinics in choosing which modalities to offer. Something must be said here about what this “scientific proof ” of efficacy is. The double-blind, placebo-controlled study for pharmaceutical drugs has been entrenched in the United States since 1962. Since that time, this method has been exalted as the only true scientific method by which all medical research must now be conducted. It is hard to believe that no amount of clinical evidence or other forms of scientific evidence will suffice for this “true and ultimate scientific method.” The author has heard the lament and cry of dozens of practitioners concerning the difficulty of developing a placebo for such things as massage so that we will never even know if it is effective! This reasoning is faulty. The method and FDA regulation set forth in 1962 was put into place to determine whether drugs were safe and effective. If a method is safe, it does not need scrutiny in this regard, unless one touts that doing anything at all is “unsafe.” For this view, the author sighs and places his face in his hands. If living is unsafe, the solution for you is alarming because it involves not living.

The “effective” part of the equation has become dependent on the placebo variable, because it has been defined to mean “more effective than placebo.” The whole “placebo effect” was defined when it was discovered that persons given something—anything that they thought was a cure—got better whether or not it contained an intended active pharmacological agent. Here it is in frightening nonscientific terms: compared to a control group with no treatment, a sham, or nonsense treatment, is effective for about one-third of persons suffering from clinically verifiable illness. Now, here is a vast curiosity: the same “scientific” persons who know full well that this placebo effect exists, and use it to “prove” that CAM interventions are fanciful ideas that do not work, also purport that no scientific evidence proves a mind/body connection, and that, therefore, mind/body interventions cannot work. This is a curious paradox. This placebo effect is further discussed in the Ayurveda section that follows.

For this placebo question, researchers now compare many CAM practices to drugs that have already been proven more effective than placebo. If a CAM procedure, then, shows equal or better results, it can be proclaimed effective. In the same vein, long-term clinical evidence and observational studies can be used to determine some level of efficacy. Although testimonials do not prove efficacy and may merely show a “placebo of choice” for a patient, it must be asked, “If that procedure is safe and effective for that person, what is the problem?” As long as people understand that “miracle cures” do not exist, and provided CAM clinics do not mislead people into believing in such cures, it may be both reasonable and ethical to offer services that do not have a single shred of “scientific proof.”

Alternative Medical Systems

The first domain in the classification structure is alternative medical systems. This domain is the broadest in scope. In other cultures, the conventional Western medical system would be classified within it. It is the most confusing category, as it may include some or all of the elements of other domains. The single most important factor for inclusion in the alternative medical systems domain is a method for assessment of health and diagnosis of disease. A health care system is not a “system” without a concisely developed method for assessment and diagnosis.

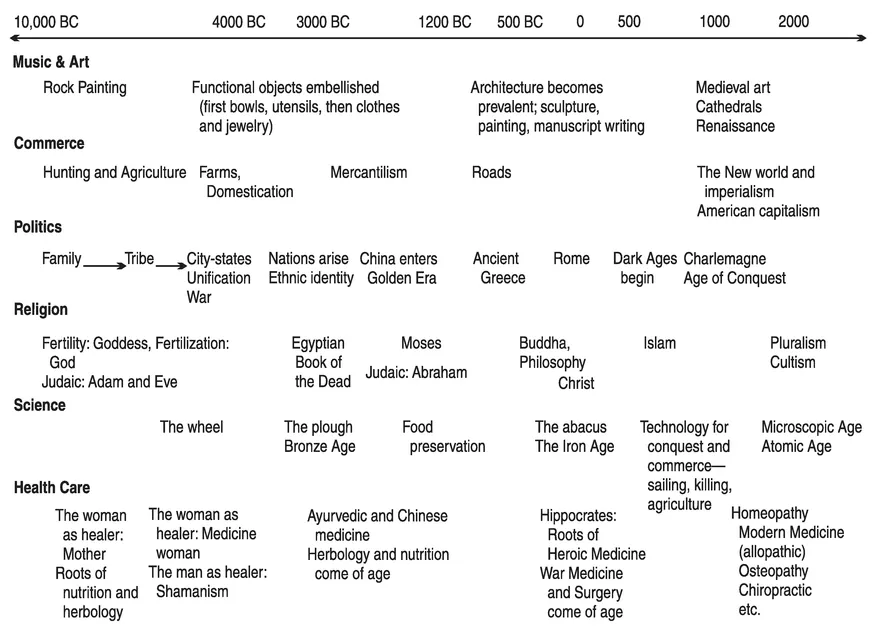

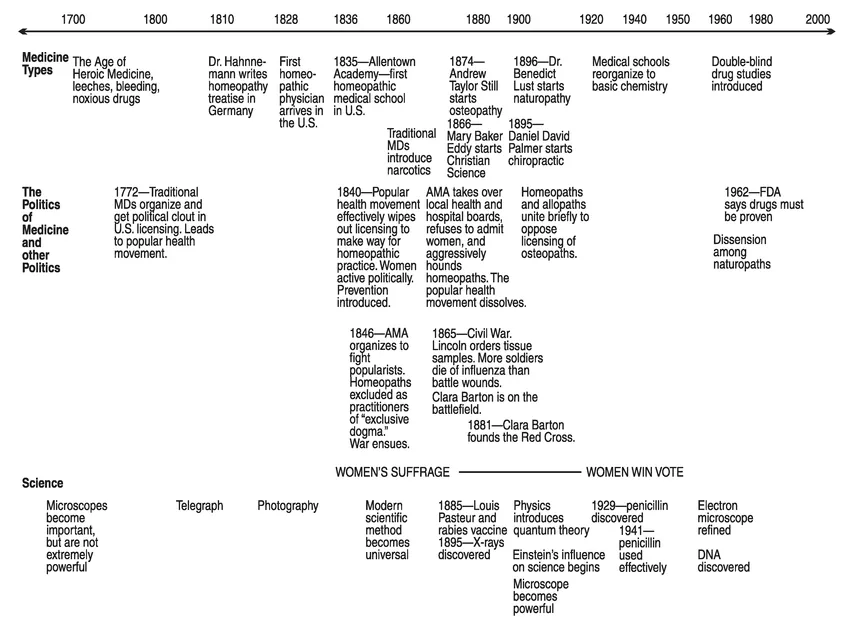

This classification is first because it recognizes that health care is primarily a cultural phenomenon, shrouded in the mists of an elongated history that stretches to a time before record keeping. Western medicine has similar deep roots as well. It did not start suddenly when the concept of the Western scientific method was introduced, and it still contains components that predate this type of validation (see Figure 1.1 and 1.2). Health care itself is much older than this. These instincts to survive and care for one another are seen in other species as well, and the ancestors of our own species likely established interdependent helping roles to perform in their social structure. Helping others survive and be well likely would have been cru

FIGURE 1.1. The history of health care graphically shown with overlapping occurrences in science, religion, politics commerce, and music/art.

FIGURE 1.2. The advent of science and politics in medicine from 1700 to the present, two very important themes in this book. The political history of medicine helps us to understand why we think the way we do about certain types of health care.

cial roles played by individuals for the survival of the entire group. The ill health of wise leaders or skilled workers before their apprentices could learn these skills might have led to great suffering and death for many members of the group. Health care, therefore, became a necessity for the ancestors of our species. This role of health care provider, in most instances, was and still is performed by the head female or mother of the family unit. This intimate form of health care has a sustained prevalence in many cultures throughout the world and should not be taken lightly.

A dramatic example of this intimate health care appeared in the alumni newsletter of Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It reported that William Fair, a renowned cancer surgeon, was diagnosed with a colon tumor. After two surgeries and a year of chemotherapy the cancer continued. No progress ensued until his wife Mary Ann insisted that he try an alternative approach: meditation, yoga, a change in diet, and Chinese herbs led the tumor to shrink. Fair claims he scientifically evaluated his options when selecting his alternative treatments, and now he lectures about the use of complementary and alternative therapies, but it was his wife’s role as their family health care manager that led him in the right direction, despite his own expertise and experience in the field (Clendenin, 2000).

At the time health care began to organize as a recognizable discipline, civilization itself was emerging from familial and tribal forms of social structure. The dynamics of cooperation and oppression coalesced in order to create improved and enhanced living conditions, in order to bend the will of the many to the will of the few. Clashes occurred and wars were declared; this dynamic struggle to fight and to tend to the wounded is inexorably attached to the advancement and knowledge of organized health care.

The advent of religion and the pursuit of thought in an organized manner in the ancient cultures of India, China, and Greece led to the creation or formalization of the nurturing, or feminine, form of health care. The scientific method of observing and reflecting on thousands of health cases, along with what were essentially trial-and-error treatment methods, were drawn together with meditative thought in ancient India. Causes and effects were observed and recorded. An entire scientific explanation for the construct of the universe was created and written down in the ancient Indian Vedas, the earliest Hindu sacred writings. Buddhists also played important roles in recording these observations, including the effort of the first Dalai Lama who called physicians from both China and India to systematically record their knowledge, thus creating the Tibetan medicine system. In Greece, it was the same, with great observers of nature and philosophers such as Hippocrates giving the first formalized direction in health care in the West.

Chinese Medicine

As one of the oldest and most detailed systems of health care, Chinese medicine has recently returned to some prominence in Western cultures because one of its components, acupuncture, has had considerable success in meeting current randomized-trial standards for efficacy. For the purposes of reviewing the literature here, meta-analyses have been used whenever possible. Meta-analyses of studies about the effects of acupuncture on pain show positive differences between acupuncture and no intervention, and equal results between acupuncture and other therapies (Melchart et al., 1999; Ernst and White, 1998; Riet, Kleijnen, and Knipschild, 1990; Patel et al., 1989). However, the use of placebo or “sham acupuncture” continues to present a problem in these studies. Most of the meta-analyses authors suggested caution and warned about what they felt were poorly constructed studies. Acupuncture was catapulted into the forefront of CAM modalities in 1997 when The New York Times, on November 6, published it as front-page news (Weil, 1997a). The original press release from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stated,

A consensus panel convened by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) today concluded there is clear evidence that needle acupuncture treatment is effective for postoperative and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting, nausea of pregnancy, and postoperative dental pain. The twelve-member panel also concluded in their consensus statement that there are a number of other pain-related conditions for which acupuncture may be effective as an adjunct therapy, an acceptable alternative, or as part of a comprehensive treatment program but for which there is less convincing scientific data. These conditions include but are not limited to addiction, stroke rehabilitation, headache, menstrual cramps, tennis elbow, fibromyalgia (general muscle pain), low back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and asthma. (NIH, 1997)

This consensus panel derived its observations from what it felt were several good single studies. After this time, the AMA started reporting the research in earnest and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) began to brim full with positive acupuncture results. An online index for JAMA listed 176 articles published from 1997 to 2001, most of them quite favorable (JAMA, 2001). The odd thing is that positive results were scant for acupuncture before this time. This may illustrate an important point about politics and science: the panel was a political body, which issued an opinion based on unquoted sources. Since the panel was U.S. government sponsored, its opinion entrenched itself in public opinion (especially since it was reported in The New York Times) and was picked up by the prestigious AMA. This may also indicate an important factor in the effectiveness of any health modality: cultural acceptance.

Ayurveda

Between 3,000 and 6,000 years ago, the Indian Vedas were established, first as an oral tradition and then as sacred writings, ushering in this health care system of India (Frawley, 1989). Since this is the author’s base discipline, it should not be construed that in-depth observations in this section are exclusive to Ayurveda, or that other systems of health care do not have methodologies and insights as effective or more effective than that of Ayurveda.

Ayur is the Sanskrit word for “life,” and veda the word for “science.” It can also be translated as the “study of longevity.” This is important to understanding the purpose of Ayurvedic intervention and prescriptions: to prolong life in order to pursue spiritual goals. This clearly ranks the importance of the “holistic trinity” of mind, body, and spirit—something that most religious or spiritual traditions might agree with, but that most health practices do not cover. This is, however, inseparable from the Ayurvedic view.

It is difficult to locate studies on panchakarma, the main Ayurvedic therapeutic technique that focuses on using the body’s natural systems of elimination to cleanse and detoxify. Since Ayurveda is heavily lifestyle oriented, most of the interest in this modality has focused on diet and herbs, with those interested in metaphysical or “new age” ideals, focusing on color and gem therapy, as well as chakra balancing (Chakras are metaphysical energy crossroads where the nadis—similar to the Chinese meridians—intersect. These energy centers, when balanced, are considered to affect physical organs, emotional and mental states, and spiritual development.) and the more spiritual aspects of the discipline. The U.S. National Library of Medicine available via their Web site, Medline, contains the most significant studies.

In review of all these alternative medical systems, a question arises: Should Western consumers afford the same respect to the medical systems of other cultures as they do their own? (This is a double-edged sword! U.S. citizens, especially, are sharply critical of their medical care.) It seems clear that only simple arrogance would discount the scientific methods followed by another culture, even if those methods do not match those of our own. The question of scientific method as required by federal authorities—such as in drug approval—is a study unto itself. Many criticisms of CAM assert that it should have to hold up to the same scientific rigor as other medical treatments (Council on Scientific Affairs, 2001) and yet it is little understood that the whole process of drug trials is a relatively recent U.S. phenomenon from the 1960s, which is not as well managed as it is touted as being (Weil, 1995, 1980). The placebo effect in drug trials has never been well accounted for. The fact that a sugar-containing pill is used for comparison purposes (as sugar has a specific metabolic effect and chemical structure) is, perhaps, one of the most fundamental mistakes of this method.

The rigors of Ayurveda for effectiveness in its own structure as a science rely on the one common element of science regardless of culture, which is observation. However, Ayurvedic observation is a passive activity (Frawley, 1989). Ayurveda as a science does not allow for the introduction of theory into observation—at least not beyond the concept that one is going to try out an idea. Hypotheses for results are quite strictly forbidden. In addition, a meditative state must be achieved by the observer, so that such things as hypotheses can be kept at bay while the observed subject reveals its true nature to the scientist. In other words, through formal tradition and training in mind-discipline techniques such as meditation, Ayurveda as a science has a means for eliminating bias. It also stands to reason that a health care system with clinical application ranging in thousands of years has a basis in science. There would have to be some efficacy and safety in most of the methods, or it would not be so wide...