6

THE HOME LEARNING ENVIRONMENT AND ACHIEVEMENT DURING CHILDHOOD

ERIC DEARING AND SANDRA TANG

The home serves as children’s first library, their first laboratory, their first art studio, and their first playground. In their homes, children make initial explorations into literacy, mathematics, science, art, and music. Indeed, it is in the home that children formulate and test some of their first hypotheses about the nature of the world, building and progressively refining their knowledge and skills as well as their learning expectations, beliefs, goals, and strategies. Accordingly, the home environment has long been considered central in shaping children’s growth, although most scholars now reject socialization theories that gave little regard to genetics and the ways that children also shape their homes (Bjorklund & Yunger, 2001; Collins, Maccoby, Steinberg, Hetherington, & Bornstein, 2000; Kellaghan, Sloane, Alvarez, & Bloom, 1993; Maccoby, 1984, 1992).

OVERVIEW

In this chapter, empirical work on home learning environments and their role in children’s achievement is reviewed. To organize this work, recent theoretical advances addressing the role of sociocultural contexts in children’s development are relied upon (e.g., Chase-Lansdale, D’Angelo, & Palacios, 2007; García Coll et al., 1996; Magnusson & Stattin, 1998; Spencer, 2006). In addition, existing conceptual frameworks of the home learning environment were helpful in organizing the present chapter (e.g., Bornstein, 2006; Bradley & Corwyn, 2004; Brooks-Gunn & Marksman, 2005). Building on these frameworks, the goal of the chapter is to answer the question: What characteristics of children’s homes matter for their achievement?

Developmentally Salient Domains of the Home Environment: What Matters for Children’s Achievement?

Compared with the young of other species, children are unusually dependent on their parents. Because of the large amount of child brain growth that occurs postnatal, and because human society is exceptionally complex, parents invest extensive resources and time in child-rearing across several years. As Bjorklund and colleagues point out, Homo sapiens “have taken parenting to new heights” (Bjorklund, Yunger, & Pellegini, 2002, p. 3).

Children’s safety and survival are a parenting priority, particularly when resources are scarce or risk is pervasive (Bowlby, 1982; 1988; LeVine & White, 1897). Beyond these basic needs, parents also use the home as a learning environment to educate their children for successful adaptation to the cultural, physical, and social milieu, passing on knowledge and life skills that children use to their advantage (Bjorklund et al., 2002; Bornstein, 2006; Harkness & Super, 2002; Lerner, Rothbaum, Boulos, & Castellino, 2002; LeVine & White, 1987). Parental investment in children within the home learning environment involves processes of socialization toward particular value orientations, but it also involves parents passing along what Swidler (1986, p. 273) referred to as a cultural “toolkit” of habits, skills, and styles” that provide “strategies of action” that children may use to thrive. These value orientations and toolkits are shaped by parents own socialization experiences, biologically-based motivation systems, intuitive parenting skills, the greater sociocultural context, and children themselves (Bowlby, 1988; Fleming & Li, 2002; LeVine & White, 1987; Papoušek & Papoušek, 2002).

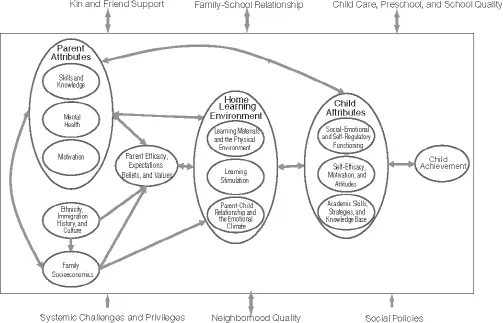

In Figure 6.1, a conceptual model is provided that helps structure the discussion of the home learning environment, depicting both physical and psychosocial elements of the home and extended developmental contexts as well as intra-psychic processes relevant for child achievement. The home learning environment is illustrated as one component of a larger child-family system that influences, and is influenced by, child achievement. From left to right, pathways of mediation are noted within this system, moving from relatively distal elements on the left that generally have indirect effects on achievement to relatively proximal elements on the right that generally have direct effects on achievement. Also highlighted in the figure are a few of the many connections between the child-family system and contexts outside the family that have either direct (e.g., child care) or indirect (e.g., social policy) implications for both the home learning environment and child achievement.

Figure 6.1 Conceptual model of the home learning environment and its connection to more general family systems, child achievement, and developmental contexts outside the family.

An exhaustive list of contextual elements and processes inside and outside of children’s homes cannot easily be included in a single figure (nor can all possible connections within the system), and encircling unique elements of the system necessarily oversimplifies what are, in reality, porous boundaries and dynamic subsystems with mutual influences on one another. Moreover, although not explicitly illustrated, three points are critical for understanding the meaningfulness of children’s home learning environments. First, children’s achievement is generally the net result of child vulnerabilities and competencies combined with contextual risks and protective factors (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Sameroff, 1975; Spencer, 2006). Second, the optimal home learning environment for promoting children’s achievement is, in part, determined by person-environment fit (Lerner, 1983; Magnusson & Stattin, 1998); for example, the optimal complexity, frequency, and intensity of experiences in the home are dependent on child developmental stage (Eccles et al., 1993). Third, associations between the more general system depicted in the figure, the home learning environment, and children’s achievement are often bidirectional, non-linear, non-additive, and changing with maturation (Gottlieb, 1998; Lerner et al., 2002; Sameroff, 2000). Yet, with these complexities in mind, much evidence has accumulated over decades of work on (a) the consequences of home learning environment quality for children’s achievement, (b) the mechanisms by which these consequences are transmitted to children, and (c) the determinants of home learning environment quality.

Organizational Framework of the Home Learning Environment

Several groups of theorists have offered frameworks to help organize families’ diverse and complex child-rearing efforts. Some frameworks organize the home environment as it is relevant for child growth broadly construed, including cognitive, language, and social-emotional growth. Notable frameworks of this type include those proposed by Bornstein (e.g., Bornstein, 2006) and Bradley and colleagues (e.g., Bradley & Corwyn, 2004). On the other hand, some frameworks have focused on the relevance of the home environment for narrowly defined domains of achievement. Two notable examples of this latter type include a framework for understanding parenting effects on school readiness provided by Brooks-Gunn and Markman (2005) and a framework for understanding home environment effects on literacy development provided by Hess and Holloway (1984).

Importantly, across these broad and narrow frameworks, there are many points of convergence with regard to home environment characteristics that matter for children’s growth. Regarding children’s achievement, these points of convergence indicate at least three elements of the home learning environment that are critical for promoting children’s achievement: (a) materials that stimulate children’s learning within a physical environment that is structurally conducive to learning, (b) parent engagement in activities with their children that stimulate learning, and (c) a parent-child relationship and emotional climate that is supportive of learning. Each of these three elements is considered in greater depth.

Learning Materials and the Physical Environment of the Home

Children learn about the world and themselves through interaction with the world and objects in it (Piaget, 1950, 1951, 1985). Indeed, both animal and human studies highlight the impact of an enriched environment on brain development. In a classic series of animal studies, for example, Greenough Black, and Wallace (1987) demonstrated that complex environments with access to stimulating toys (e.g., climbing ladders and spinning wheels) are necessary for optimal synaptic growth in young rats. These studies suggest that a basic level of material resources in the environment is likely necessary for typical brain development and, on the other hand, deprivation limits neural growth (Blakemore & Firth, 2005). In fact, consistent with the animal studies, infants raised in extremely deprived orphanages display later cognitive deficits perhaps resulting from neural damage, although some of these children also evidence considerable cognitive recovery when adopted into enriched home environments (Rutter & O’Connor, 2004).

Learning Materials Most studies on the value of home learning materials for achievement do not have the design advantages of animal studies (randomized experiments) or orphanage-adoption studies (natural experiments). Nonetheless, many non-experimental between-family comparisons have indicated a strong correlation between having learning materials in the home and nearly all areas of achievement. Children’s access to literacy materials in the home, for example, is an excellent predictor of literacy achievement. The number of children’s books and other print materials within the home predict reading outcomes contemporaneously such that children from homes that contain high quantities of print materials have better vocabulary skills, show more interest in book reading, and have higher reading achievement scores than those from homes with fewer print materials (Connor, Son, Hindman, & Morrison, 2005; Morrow, 1983; Sénéchal, LeFevre, Hudson, & Lawson, 1996; Wahlberg & Tsai, 1985).

Bradley, Caldwell, and colleagues noted the developmental value of material resources in their series of studies on the home learning environment and achievement (e.g., Bradley & Caldwell, 1984; Bradley, Caldwell, & Rock, 1988). Their work pointed toward a heightened importance of access to home learning materials during infancy and toddlerhood, findings consistent with Piaget’s emphasis on physical exploration of the environment during the sensory-motor stage of early development. The presence of play materials and toys in children’s homes at age 2, in fact, was a robust predictor of achievement through age 10, even controlling for contemporaneous levels of learning materials in the home (Bradley et al., 1988). Yet, researchers have also noted the importance of materials in middle-childhood and beyond. Simpkins and colleagues (Simpkins, Davis-Kean, & Eccles, 2005), for example, documented associations between parents’ provision of math and science toys and games in the home during the elementary-school years and children’s involvement in math and science activities outside of school.

For learning materials, variety and match with developmental stage also matter. Children’s reading comprehension, for example, is promoted by having access to many different kinds of reading materials (Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). It is not clear, however, that diversity of experience is always explicitly designed by parents. Although some families provide a range of materials and products purchased solely for the purposes of enriching the learning of children (e.g., educational games, children’s books), other families provide variety by giving children access to materials not originally intended for learning stimulation per se (e.g., magazines, coupons, religious reading materials such as the Bible), but are stimulating nonetheless (Purcell-Gates, 1996).

In addition, materials in the home are effective only to the extent that they provide challenge that is aligned with children’s cognitive maturity, skill levels, and interests (Bradley, 2006; Eccles et al., 1993; Eccles & Midgley, 1989). During infancy, access to brightly colored concept books that have very large pictures accompanied with a few words of print is important (Morrow, 2001). Toddlers and children in kindergarten should have a wider variety of print materials: alphabet and number books, poetry, nursery rhymes, and books with limited vocabulary that have pictures matching the text (Morrow, 2001). Once children develop foundational reading skills, more challenging materials (e.g., chapter books) are appropriate, and considerations for topics of interest and child-specific curiosities become relevant through middle-childhood and adolescence (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Morrow, 2001).

Organization and Physical Quality of the Home Beyond material resources, the organization and structural quality of the physical home environment are also relevant for children’s growth, albeit areas that have received less study by child development scholars (e.g., Bradley & Corwyn, 2004; Evans, Kliewer, & Martin, 1991; Evans, Wells, & Moch, 2003). In one interesting set of studies on the organization of the home, Dunifon and colleagues (e.g., Dunifon, Duncan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2001, 2004) have found that home cleanliness is predictive of children’s years of educational attainment and, in turn, later earnings as an adult. The proclivity towards cleanliness and organization may be determined, in part, by personality traits that parents pass on to children, and these personality traits may also have achievement benefits. Dunifon and colleagues noted, however, that the cleanliness of children’s homes during childhood is more strongly predictive of later outcomes such as earnings during adulthood than is the cleanliness of their homes during adulthood. This finding appears most consistent with environmental, rather than heritable, explanations of the impact of home cleanliness on children’s achievement.

Home cleanliness findings may also provide insight into the importance of household efficiency. Because Dunifon and colleagues statistically controlled for the amount of time that parents spent cleaning the house, cleanliness may have been an indicator of efficient investment in their children and the household. Based on historical and cross-cultural evidence, LeVine and White (1987, p. 289) argued that “there is probably an optimal strategy of parental investment, i.e., a most efficient way of maximizing culture-specific parental goals” in every society. On the other hand, there is accumulating evidence that the physical home environment per se (i.e., the organization, physical integrity, and safety of the home) has implications for children’s achievement (Evans, 2004, 2006).

In comprehensive reviews, Evans (2004, 2006) has documented the implications of physical environments for children’s growth, integrating evidence of both direct and indirect effects of home organization and physical structure on children’s achievement. As a function of housing quality and location, for example, some children are exposed to higher concentrations of toxins linked with cognitive impairment such as lead, mercury, and PCBs (e.g., Needleman et al., 1979). Noise levels in the home matter as well; children whose homes have high noise levels (e.g., from transportation) are at risk for reading, memory, and attention problems. This is likely due to both the direct negative impact that noisy environments have on children’s efforts to learn and through the negative impact that noise can have on parents’ levels of stress and patience (e.g., Evans & Maxwell, 1997). Furthermore, home size, crowding, and access to outside play areas are relevant for learning in the home (Evans, Lepore, Shejwal, & Palsane, 1998). More densely crowded homes with little access to natural play settings limit exploration and learning opportunities and, in turn, are associated with poor cognitive, literacy, and achievement outcomes. In addition, the effects of crowding can be indirect, mediated by the extent to which parents engage in learning stimulation. In densely crowded homes, for example, parents may read less often with their children.

Learning Stimulation

Several theoretical perspectives on children’s development have emphasized the important role of parent stimulation of children’s learning through parent-child interaction, including ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998), sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978), and social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997). In particular, sociocultural theory emphasizes the central importance of parent-child interactions for stimul...