During the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, visible markers of the past – plaques, information boards, museums, monuments – have come to populate more and more land- and cityscapes. History has been gathered up and presented as heritage – as meaningful pasts that should be remembered; and more and more buildings and other sites have been called on to act as witnesses of the past. Many kinds of groups have sought to ensure that they are publicly recognised through identifying and displaying ‘their’ heritage. At the same time, museums and heritage sites have become key components of ‘place-marketing’ and ‘image-management’; and cultural tourism has massively expanded, often bringing visitors from across the world to places that can claim a heritage worth seeing.

This book explores a particular dimension of this public concern with the past. It looks at what I call ‘difficult heritage’ – that is, a past that is recognised as meaningful in the present but that is also contested and awkward for public reconciliation with a positive, self-affirming contemporary identity. ‘Difficult heritage’ may also be troublesome because it threatens to break through into the present in disruptive ways, opening up social divisions, perhaps by playing into imagined, even nightmarish, futures. By looking at heritage that is unsettling and awkward, rather than at that which can be celebrated or at least comfortably acknowledged as part of a nation’s or city’s valued history, my aim is to throw into relief some of the dilemmas about its public representation and reception. Doing so highlights and unsettles cultural assumptions about and entanglements between identity and memory, and past, present and future. It also raises questions about practices of selection, preservation, cultural comparison and witnessing – practices which are at least partly shared by anthropologists and other researchers of culture and social life.

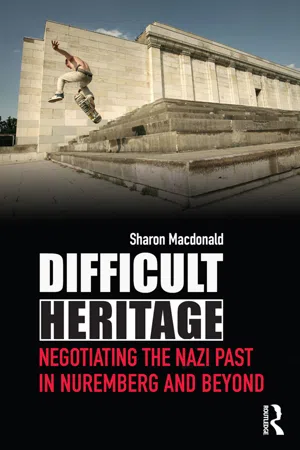

At its core, this book tells a story about one particular especially difficult heritage.1 This is the struggle with Nazi heritage – especially remaining architectural heritage – in the city of Nuremberg, Germany; a city which has, perhaps more than any other, found its name linked to the perpetration of the appalling and iconic atrocity of modernity – the Holocaust. To give an account of how Nuremberg has negotiated its difficult heritage, and how visitors to the city experience it today, I draw on a combination of historical and anthropological perspectives in order to explore changes over time as well as to try to see how different players, practices and knowledges – local and from further afield – interact, and are brought into being, to shape the ways in which the city’s past is variously approached and ignored. By telling this detailed and sometimes untidy story, my intention is also to provide a located position from which to think further about – and to some extent complicate – accounts of how Germany has faced its Nazi past and what this might mean to people today. More generally still, it is to provide some coordinates for understanding difficult heritage – wherever it is found – and its implications.

Difficult heritage

Wars, conflict, triumph over foreigners, the plunder of riches from overseas – these are the stuff of most national histories. Yet whether they are perceived as troubling for contemporary identity may vary considerably; and what was once seen as a sign of a country’s achievement may later come to be understood as a reason for regret. Colonialism, for example, once a source of great national pride for colonising countries has increasingly – though not unequivocally – come to be regarded as a more problematic and even shameful heritage; and many explicit depictions of colonial might now languish in museum basements. Wartime episodes that were regarded as military triumphs can also become sources of embarrassment. In Japan, for instance, the 1937 Rape of Nanking, in which the Japanese Imperial Army brutally slaughtered or tortured tens of thousands of Chinese, remains a national achievement for some, and is repeated as such in school textbooks, but has become a mortifying memory for many other Japanese who know about it.2 The allied bombing of Japanese cities during World War II, and of German cities, especially Dresden, have likewise become increasingly controversial over the years, and the subject of continued memorial and museological dispute.3

While what counts as ‘difficult heritage’ – or indeed worthy heritage – may change, however, the idea that places should seek to inscribe what is significant in their histories, and especially their past achievements, on the cityscape is longstanding and widespread. In a pattern consolidated by European nation-making, identifying a distinctive and preferably long history, and substantiating it through material culture, has become the dominant mode of performing identity-legitimacy. ‘Having a heritage’ – that is, a body of selected history and its material traces – is, in other words, an integral part of ‘having an identity’, and it affirms the right to exist in the present and continue into the future. This model of identity as rooted in the past, as distinctively individuated, and as expressed through ‘evidence’, especially material culture, is mobilised not only by nations but by minorities, cities or other localities.4 Because of the selective and predominantly identity-affirmative nature of heritage-making, it typically focuses on triumphs and achievements, or sacrifices involved in the struggle for realisation and recognition. Events and material remains which do not fit into such narratives are, thus, likely to be publicly ignored or removed from public space, as have numerous monuments erected by socialist regimes or former colonisers. Or, as Ian Buruma writes of the lack of information about Nanking in Japanese school history texts, they may be ‘officially killed by silence’.5 More dramatically, silencing may involve the physical destruction of material heritage, such as the destruction of mosques as part of ‘ethnic cleansing’ and the obliteration of the Oriental Institute and Bosnian National Library in Sarajevo – both home to vast archival evidence of Bosnian history – by Serb extremists during the Bosnian War.6

Yet ignoring, silencing or destroying are not always options – and the awkward past may break through in some form. This may be because the events are too recent and their effects still being felt, though recency is not a guarantee of public acknowledgment, as we will see below. It may be because some groups or individuals – ‘memorial entrepreneurs’ – try to propel public remembrance, perhaps of events of which they were victims or which they feel morally driven to commemorate, perhaps because they fear that forgetting risks atrocity being repeated in the future.7 In some cases, groups or individuals outside the locality, and even beyond the nation, demand that past perpetrations are publicly recalled and exposed. In others, material remains of past events or regimes may defy easy obliteration and thus act as mnemonic intrusions. Archaeological finds or historical scholarship may embarrass accepted narratives. Or public recognition may be prompted by the fact that, while a troubling history may be uncomfortable, it is also of heritage-interest, attracting tourists and bringing revenue. In all such cases – which in reality are likely to be combinations of motives and actors – heritage-management is fraught with multiple dilemmas.

In the field of heritage and tourism management, Tunbridge and Ashworth have devised the term ‘dissonant heritage’ to express what they see as the inherently contested nature of heritage – stemming from the fact that heritage always ‘belongs to someone and logically, therefore, not to someone else’8 – though which may be relatively ‘active or latent’. They chart numerous kinds of dissonance, including where tourist authorities promote a range of differing images of a place and what they call ‘the heritage of atrocity’,9 in which, they argue, ‘dissonance’ may provoke intense emotions and be bound up with memories that have ‘profound long-term effects upon [a people’s] self-conscious identity’.10

Like others, Tunbridge and Ashworth distinguish between atrocity heritage that is primarily concerned with victims – for example, Nazi concentration camps or Khmer Rouge torture buildings – and that which is principally of perpetration.11 In many cases, of course, it is hard to maintain a clear distinction between sites of victims’ suffering and those of perpetration – concentration camps and torture chambers were clearly both. Nevertheless, there are places – such as, say, the Wannsee villa in Berlin or Hitler’s complex of buildings on the Obersalzburg in Bavaria – which are part of the apparatus of perpetration but not locations in which suffering was directly inflicted. These might be seen as sites of ‘perpetration at a distance’, to adapt some language from actor network theory.12 While all sites of atrocity raise difficulties of public presentation – including the question of how graphically suffering is depicted – there are some specific dilemmas raised by sites of perpetration at a distance. In particular, precisely because heritage-presentation and museumification are typically regarded as markers of worthwhile history – of heritage that deserves admiration or commemoration – their preservation and public display might be interpreted as conferring legitimacy of a sort.13 This is part of a ‘heritage effect’ – a sensibility grounded in particular visual and embodied practices prompted by certain kinds of spaces and modes of display.14 Moreover, there is also the risk that such sites might become pilgrimage destinations for perpetrator admirers. This argument surfaced in the debates over the legitimacy of later public uses of the sites just mentioned, both of which incorporate educational displays (though Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest on the Obersalzburg also, controversially, opened as a luxury hotel in 2005). In other instances, as with the site of Hitler’s bunker in Berlin, this argument has been used to prevent any kind of public marking.15

In this book, my aim is neither to try to classify different types of heritage, nor to present a general survey, as do Tunbridge and Ashworth, useful though these may be. ‘Difficult heritage’, as I use it here, is more tightly specified than their notion of ‘dissonance’ insofar as it threatens to trouble collective identities and open up social differences. But beyond that, my approach here is to explore ‘difficult heritage’ as a historical and ethnographic phenomenon – and as a particular kind of ‘assemblage’ – rather than to establish it as an analytical category.16 This means looking at how heritage is assembled both discursively and materially, at the various players involved, at what they may experience as awkward and problematic, and at the ways in which they negotiate this. My interest here includes the kinds of assumptions that are made about the nature of heritage, identity and temporality, the terms in which debates about ‘difficult heritage’ are conducted, what is ignored or overlooked, and how agency is accorded – all of which can be seen as constituents of what is sometimes called ‘historical consciousness’ (which is a recognised field of historiography within Germany).17 As Jeffrey Olick has noted, the idea of ‘historical consciousness’ usefully avoids reifying a sometimes spurious distinction between ‘history’ and ‘memory’;18 and it directs attention not just to the content of history or memory but also to questions of the media and patterns through which these are structured, as well as where lines between, say, history and memory might be drawn in particular contexts.

In some historical consciousness theorising, especially in the German tradition, there is an emphasis upon identifying universal ‘orientations’, in, for example, how people understand the relationship between past, present and future. Rather than revealing universally shared patterns, my own more modest aim is to highlight elements of a repertoire of possible approaches to difficult heritage and to chart some of their implications. That is, I seek to identify a non-exhaustive range of negotiating frames and tactics through which some kinds of past are evoked and engaged within public culture. Unlike the universalist approach to historical consciousness, mine here is not concerned with presumed shared mental patterns but addresses the social and cultural situations and frames in which heritage – and difficult heritage – is assembled and negotiated. These situations and frames are simultaneously local and beyond local. That is, they involve specific local conditions and actors but these never act in a vacuum, even when they are actively producing ‘locality’. Instead, as we see below, local actions are frequently negotiated through comparisons with other places, through concepts and ideas produced elsewhere and that may even have global circulation, and through the sense of being judged by others. They are also negotiated in relation to legislation, political structures and economic considerations which are rarely exclusively local.

As I am interested in heritage making and historical consciousness as social and cultural practices, I am concerned to look not just at ‘history products’ (e.g. a heritage site) but at the practical activities and sometimes rather banal events involved in their production and consumption. I am also concerned with the sometimes messy – and sometimes strikingly consistent, rhythmic and predictable – course of negotiations, and the social alignments and identifications that such negotiations may produce. For these reasons, my focus is on a specific, in-depth case – that of Nuremberg – and my hope is that this can enable me to illuminate better some of the assumptions, oversights, silences and complexities of negotiating difficult heritage than might a wider survey.

As the section below briefly indicates, however, struggles with difficult heritage are extremely widespread, and increasingly likely to result in public display. Moreover, as the Nuremberg study shows too, what goes on in any particular country or city is never culturally isolated – even if it may sometimes feel like it to those involved. Rather, the local is negotiated into being in relation – sometimes through cultural analogy, sometimes via shared concepts and practices, sometimes through the intervention of actors from outside, and sometimes through explicit opposition – to ‘elsewhere’, be that other cities nearby or other parts of the world.