- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Islam: The Basics

About this book

Now in its second edition, Islam: The Basics provides an introduction to the Islamic faith, examining the doctrines of the religion, the practises of Muslims and the history and significance of Islam in modern contexts. Key topics covered include:

- the Qur'an and its teachings

- the life of the Prophet Muhammad

- gender, women and Islam

- Sufism and Shi'ism

- Islam and the western world

- non-Muslim approaches to Islam.

With updated further reading, illustrative maps and an expanded chronology of turning points in the Islamic world, this book is essential reading for students of religious studies and all those new to the subject of Islam.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE MESSENGER

There can be very few people in the world who have not heard of Muhammad, Prophet of Islam. For Muslims, of course, he is the orphan who became the apostle of God, communicating to all humankind the message of Divine Oneness and the key to man’s existential dilemma: islām or conscious submission to the will of the One true Lord of all worlds. For those who choose not to follow his teachings, he is a man whose career formed the cornerstone upon which a vast empire, spanning from Spain to India, was founded, and the enigmatic, often controversial, founder of a world religion that today claims the allegiance of over a billion souls. As such, he is often lauded – even by his detractors – as both prophet and statesman, a figure whose significance is such that he was once voted the most influential man in world history by a panel of Western writers and academics. Few who have read anything about him come away without having formed an opinion concerning him, and many who know nothing at all about him will often venture an opinion anyway, swayed possibly by the latest news item on ‘Islamic fundamentalism’, or simply because it is human nature to pontificate on matters totally beyond our ken. But who is Muhammad, and what is his role in the genesis of that enigma known as Islam?

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT MUHAMMAD AND HOW TO WE KNOW IT?

It has been argued, and not without justification, that we know more about Muhammad than we do about any other classical prophet or founder of religion. The wealth of information available on almost every aspect of the man’s life is astounding, from detailed accounts of his role as prophet to the most intimate minutiae of his private life. Not only can we read about the trials and tribulations he faced in establishing his mission, or the wars he fought in defence of his community-state in Medina, but we can also peer directly into his private space, gleaning fascinating snippets of information on every facet of his conduct as an ordinary human being: how he ate and drank, how he behaved towards strangers, how he treated his family – and even how he urinated, took ablutions or made love to his wives. There is nothing, it would appear, that is taboo, and no place in the public or private life of this exceptional individual that we cannot enter.

Yet little if any of this information is available in the Quran, which is extremely sparing in its references to Muhammad: the Quran may be all things to all people, but a biography of the Prophet it most certainly is not. In fact, the amount of concrete biographical information on Muhammad in the Quran amounts to probably no more than a handful of verses, and he is mentioned by name a total of four times in all. If the wealth of detail that we have on Muhammad does not come from the Quran, then, what is its source? In short, how do we know what we know about the Prophet of Islam?

THE HADITH

The Meccan Arabs at the time of Muhammad were not known for their written literature: while poetry was their forte, for the most part this was communicated orally, with very little of it actually committed to paper. The art of memorisation was highly prized: legends from the past, and the history of each clan, were captured in verse and handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation.

By the time of Muhammad in the late sixth century, this predominantly oral literary culture was still very much in evidence. However, with the growth of centres of commerce such as Mecca and the gradual settlement and urbanisation of the nomads, there was a commensurate rise in literacy, and in the popular perception of its importance and prestige. It is inconceivable, then, that the rise of a self-styled ‘messenger of God’ would not have been written about or at least commented on by writers and historians of the time. Equally, it is inconceivable that his close followers and companions would not have wished to record for posterity the sayings of a man whom the Quran described as a universal messenger to all humankind.

Muslims today do indeed believe that much of what Muhammad said and did was recorded for future generations. Each written account is referred to individually as a hadith, and collectively as ‘the hadith’. (The usual English translation is ‘Prophetic Tradition’ or simply ‘Tradition’.)

The overriding problem with the Prophetic Traditions is that a written record of their existence did not emerge until 200 years after the Prophet’s death, when six authoritative volumes of Traditions, each containing thousands of hadiths, were produced. Why, if accounts of the Prophet’s life were recorded while he was alive, is there no record of their existence until the middle of the ninth century? There are several possible explanations for this:

(i) Although the accounts were written down while the Prophet was still alive, they were not actually collated until the middle of the ninth century. When the six definitive volumes appeared, the sources from which they were compiled were gradually lost. Today we have the six volumes, but no record of the written sources upon which they were based.

(ii) The accounts were not written down while the Prophet was alive, but were instead handed down orally from generation to generation. Eventually it was felt that to avoid the problem of possible errors in transmission, the accounts should actually be committed to paper.

(iii) The absence of written sources prior to the middle of the ninth century makes it unlikely that anything substantial was written down in the lifetime of the Prophet, although this cannot be proved beyond all doubt. Some of the Traditions which were produced two centuries after the death of the Prophet were based on hearsay and probably do date back to the time of Muhammad; most, however, are fabrications from a later age, constructed for political or ideological purposes.

The ‘orthodox’ Muslim position is that the Traditions which emerged from ad 850 onwards are for the most part genuine, regardless of whether they were compiled from written or oral sources. Some Muslims concede that the possibility of later fabrication exists, and for this reason treat the Traditions with a certain amount of respectful caution. Non-Muslim critics of the Traditions tend either to accept the Muslim account, albeit with the obvious caveats, or to reject the whole corpus of Traditions as a later construction. The situation is not helped by the fact that the Traditions accepted as valid by the Sunni Muslims differ from the Traditions considered authoritative by the Shi’ites.

A closer look at the history and structure of the Traditions may help to show why the issue is such a controversial one.

The two main (Sunni) collections of Traditions are those made by Muhammad ibn Isma’il al-Bukhari (d. 870) and Muslim b. Hajjaj (d. 874), each of which, confusingly enough, is known as the Sahih or ‘authoritative collection’. The Sahih of al-Bukhari contains around 9,000 hadiths, while the Sahih of Muslim has around 4,000; both collections contain numerous repetitions. The fact that both authors entitled their works Sahih indicates the conviction on their part that the Traditions they had included were genuine. Other compilers – the Shi’ite collectors of Traditions in particular – concede the possibility that spurious hadiths may have fallen through the net.

The Sahih of al-Bukhari is arguably for the vast majority of Muslims the most important ‘religious text’ after the Quran, and with the Sahih of Muslim it is considered the most authoritative collection of Traditions by all Sunni Muslims. Containing approximately 9,000 Traditions in nine volumes, it is arranged thematically and deals with the sayings and behaviours of Muhammad with regard to a wide range of issues such as belief, prayer, ablution, alms, fasting, pilgrimage, commerce, inheritance, crime, punishment, wills, oaths, war, food and drink, marriage and hunting. The Sahih of al-Muslim, with approximately 4,000 Traditions, is divided into forty-two ‘books’, each dealing with a different theme.

The topics covered by al-Muslim are similar to those one finds in the Sahih of al-Bukhari. The differences in methodology employed by the two compilers is minimal. Bukhari was renowned for his precision in testing the authenticity of Traditions and tracing their ‘chains of transmission’, and he was the founder of the discipline known as ‘ilm al-rijāl (lit. ‘science of (learned) men’) or the detailed study of those individuals who transmitted hadith orally. Muslim b. Hajjaj for his part divided the Traditions into three main categories according to the level of knowledge, expertise and excellence of character of the transmitter, and also the degree to which the Tradition was devoid of contradictions, falsities or misrepresentations.

Each Tradition has two parts: a main body of text, known in Arabic as a matn, which includes the actual account of what the Prophet either said or did; and an isnād or ‘chain of transmitters’ – the list of people, reaching back to one of Muhammad’s companions, who have handed the account down orally through history. For example, a typical hadith would read as follows:

X said that Y said that W said that V heard the Prophet say: ‘…’

The text of the above hadith indicates a saying of Muhammad, uttered by him either as a general comment or word of advice, or in response to some question or other. These recorded sayings were not said by him in his capacity as Prophet, and clearly do not hold the same status as the utterances which constitute the Quran.

The hadiths do not record only the sayings of the Prophet, however: they also record his behaviour, as witnessed by others. A typical hadith of this kind would read as follows:

X said that Y said that W said that V saw the Prophet do …

The form of the hadith clearly keeps itself open to possible adulteration, by the simple process of ‘Chinese whispers’ if not by blatant manipulation or fabrication by those who wish, for whatever reason, to put words in the mouth of the Prophet. Controversy concerning the authenticity of the hadith material still continues today, with groups polarised sharply in their assessment of the validity of the Traditions not only as a reliable source for a biography of the Prophet, but also as the theoretical cornerstone of Islamic jurisprudence.

THE BIOGRAPHY OF THE PROPHET

Another important source of information on the Prophet is his biography or sira. However, this is surrounded by the same problems and controversies as the Traditions.

The biography of Muhammad is problematic in that it was not written until over a century after his death. Its author, Ibn Ishaq, was a native of Medina, where he devoted much of his time to the collection of hadith, anecdotes and reminiscences concerning the early years of the Muslim community and the life of Muhammad in particular. The work itself, produced at the beginning of the eighth century, has not survived. However, many early Muslim historians quoted from it extensively, and so it has been possible to reconstruct most of Ibn Ishaq’s book by excavating it from the writings of others.

While the sira is of immense historical importance as the earliest known source of information on the Prophet’s life, it has come under fire from many historians – quite a few of them Muslim – as unreliable, presumably on the same grounds that the hadith may be unreliable. One must, therefore, treat it with caution when trying to piece together parts of the enigmatic jigsaw that goes to make up the life of one of the world’s most illustrious figures.

There is actually much debate within the community of historians who research the birth of Islam and the rise of the Muslim world as to which, if any, of the early Muslim historical sources are of any real use at all, with some critics going so far as to say that the life of Muhammad is impossible to reconstruct, while others claim that much of what has passed traditionally as early Muslim history is, in fact, a product of later fabrication.

In the absence of viable alternatives, however, they are as reliable or unreliable as any historical source of similar antiquity is likely to be, and thus we must give the benefit of the doubt to the traditional Muslim account, which is certainly as credible as, and for the most part considerably more credible than, any of those accounts proffered centuries later by certain revisionist historians with particular axes to grind. To begin that account, we need to go back over 1,400 years to Mecca, in the Arabian peninsula, birthplace of Muhammad and cradle of the religion of Islam.

PRE-ISLAMIC ARABIA

The old idea that Islam is a religion of the desert, designed for a desert mindset, is one of those myths that seem to persist even when they have been proven false; the notion that Islam was spread by the sword is another. Almost as deep-rooted is the assumption that the history of Islam is the same as that of the Arabs, and that prior to the arrival of Muhammad they had little if any history to speak of. Yet Islam did not emerge into a vacuum; nor was its founder, or the society of which he was a part, without a past. It is to this past – the history of pre-Islamic Arabia – that we must look in order to better contextualise, and thus understand, the mindset of Muhammad, the advent of Islam, and the genesis of Muslim civilisation.

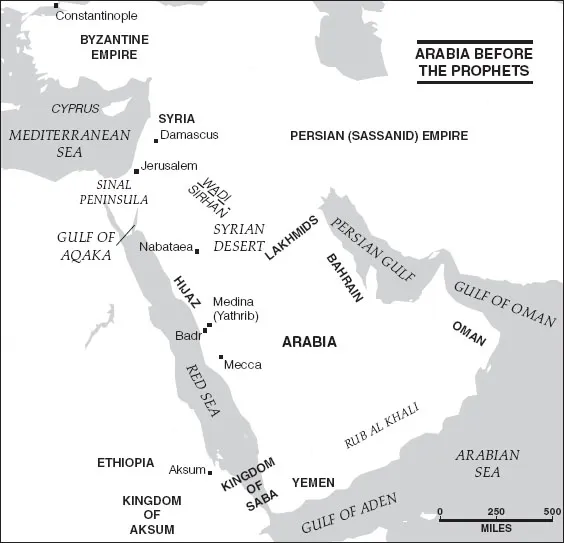

Although Arabia and the Arabs were known to the chroniclers of ancient history, for the purposes of this book we shall begin our story in the middle of the sixth century ad, some 500 years after the death of Jesus Christ. Our scene is set in the vast Arabian peninsula, an area of mainly rock and desert approximately 700 miles wide and 1,000 miles long. Those who lived there eked out their existence under the harshest of physical conditions, scorched for most of the year by a relentless sun, which made survival something of an achievement. Yet on its coasts were dotted numerous small ports, home to enterprising seafarers, forming an important part of the trade network which linked India and Mesopotamia to East Africa, Egypt and the Mediterranean. Also, for several hundred years before, and for a century after, the birth of Christ, the southern part of Arabia had been the locus of several prosperous kingdoms, with civil institutions as advanced as any in the world at that time. However, a variety of socio-economic factors led to gradual changes in the demographic structure of the peninsula. Among them, according to historians of the time, was the bursting and subsequent collapse of the great dam of Ma’rib in the Yemen. Consequently, the inhabitants were forced to migrate northwards where, untouched by the civilising influence of the two great empires of the region, namely Byzantium and Persia, the migrants formed a tribal society based on pastoral nomadism. This was the Arabia of Muhammad’s day – an Arabia which, in many respects, has changed little since.

ARAB SOCIETY AND CULTURE

Some Arab tribes in the peninsula were involved in trade between the Mediterranean and the southern seas. A larger number, however, made a precarious living in the desert by raiding other tribes or plundering trade caravans, or by herding camels, sheep and goats in a life that was lived constantly on the move. Yet the old image of the ‘uncivilised Bedouin’ is most misleading, for in fact desert life was lived to the highest of values. Qualities such as manliness, valour, generosity and hospitality were valued highly; even the intertribal raids and vendettas occurred to precise, unwritten rules. The Arabs were also lovers of poetry, producing a sophisticated literature that was communicated orally from father to son, and from tribe to tribe. Indeed, it was the unquestioning loyalty to one’s tribe, and the values it represented, that lay at the heart of Bedouin life, and the idea of individual identity outside the tribal set-up was unknown.

Figure 1.1 Arabia at the advent of the Prophet

By the end of the sixth century, certain changes had begun to occur. The population was growing, and with it the development of sedentary life. The town of Mecca was one such oasis. Situated at the junction of two major trade routes, it had enjoyed a certain amount of prestige since ancient times. More important, however, was its prominence as the most sacred city of the desert Arabs – a status it still enjoys, albeit under very different circumstances.

The pre-Islamic Arabs have often been described misleadingly as ‘pagans’. The Arabs believed in a whole host of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- A Note to Readers

- Introduction

- 1 The Messenger

- 2 The Message

- 3 The Rise of Muslim Civilisation

- 4 Belief

- 5 Practice

- 6 Spirituality

- 7 Revival, Reform and the Challenges of Modernity

- A Timeline of Events in Muslim history

- Glossary of Arabic terms

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Islam: The Basics by Colin Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Islamic Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.