eBook - ePub

Race-ing Art History

Critical Readings in Race and Art History

Kymberly N. Pinder, Kymberly N. Pinder

This is a test

Share book

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Race-ing Art History

Critical Readings in Race and Art History

Kymberly N. Pinder, Kymberly N. Pinder

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Race-ing Art History is the first comprehensive anthology to place issues of racial representation squarely on the canvas. Art produced by non-Europeans has naturally been compared to Western art and its study, which refers to a binary way of viewing both. Each essay in this collection is a response to this vision, to the distant mirror of looking at the other.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Race-ing Art History an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Race-ing Art History by Kymberly N. Pinder, Kymberly N. Pinder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunstgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

one

Black Athenas,

Semitic Devils,

and Black Magi

Reading Race from Antiquity

to the Middle Ages

1

"Just Like Us"

Cultural Constructions of Sexuality and Race

in Roman Art

in Roman Art

John R. Clarke

One of the greatest difficulties plaguing the study of Roman art is the persistent notion that the Romans were "just like us." This problematic idea forms the premise and subtext of five centuries of classical studies. If the Renaissance had a deep stock in establishing the legitimacy of early capitalist/bourgeois conceptions of the humanist individual through the study of classical texts, it was because the legitimation of princely politics and ethics required a powerful precedent—no less authoritative and powerful than the fabled Roman empire. Renaissance humanists looked to Cicero, Vergil, and Livy for ways to define the early modern state. Subsequent attempts to legitimate the prince, the absolute monarch, colonialism, nineteenth-century nationalism, and—finally and most terrifyingly—German and Italian fascism, always went back to the ancient Romans, to those same text with their histories of emperors and empire, their great lawyers, statesmen, rhetoricians, moralists, and poets.

Late twentieth-century Euro-American culture is in many ways the end product of centuries of adaptation of ancient Roman texts and cultural artifacts to fit the requirements of an increasingly capitalist, bourgeois, and colonial system. If the Romans seem to be in all things so much like "us," it is because "we" have colonized their time in history.(In this essay I use the words "we" and "us" to denote the white, male elite of Euro-American culture—the person I perceive to be the dominant voice in traditional scholarship.) We have appropriated their world to fit the needs of our ideology.

A revolution has occurred in the study of classical texts, one that has challenged those five centuries of scholarship. On one front, feminist scholars have challenged and problematized the sources in their search for that elusive person, the Roman woman.1 All the texts that have survived, written either by elite white males or by men working for them, construct—that is, make up—women. Both the poet and the jurist put words in their mouths and devise their actions, whether vile or virtuous. One will search in vain for a woman's commentary on the condition of women of any class, although by deconstructing texts scholars have succeeded in extrapolating information about the elite woman: her legal and marital status, social mores, and political power. Harder to track are the nonelite women—the greatest number of them invisible because they are ciphers, both juridically and socially: these include free nonelite women, former slaves, slaves, foreigners, and outcasts (infames) like prostitutes.

A second route of inquiry has tried to recover the diversity of people in the Roman empire by applying the models developed in sociology, economics, cultural anthropology, and geography (including urban studies and population analysis). The picture that has emerged is that of an empire loosely organized indeed. Once the Romans had conquered various peoples of the Mediterranean, they tried to rule with the lightest possible touch, preferring the laissez-faire accommodations of religious syncretism, local rule, and vassal (puppet) kings to the heavy-handed direct policing that was so expensive to maintain. As long as a town or province paid its taxes to Rome and maintained a modicum of civil order, Rome was happy to let indigenous cultures continue. Again, it seems that modern ideologies have required Roman rule to be more all-encompassing than it was in reality.2

If application of the methodologies of feminist scholarship and the social sciences has begun to expand the tunnel-vision optic of traditional classical studies of Rome, what can the study of visual representation accomplish? Central to any project using Roman visual arts to understand ancient Roman people is the realization that whereas texts addressed the elite, art addressed everybody. From official imperial art to the wall paintings in a Pompeian house, Roman art consciously embraced a far broader audience than the texts. My recent work has focused on two specialized genres of Roman art, images of human lovemaking and representations of the black African, in an effort to understand the nonelite viewer, the female viewer, and even the non-Roman viewer.3 It is from this work that I would like to draw two illustrations of how contextual readings of visual representations reveal the great differences between Roman culture and our own.

The typical literature on sexual representation in Roman art presents a variety of imagery in many media—from wall paintings to ceramics and metalwork—under the rubric of "erotic" art.4 Authors then try to tack texts onto photographs of these representations: the reader sees a photograph of a satyr and maenad copulating on one page, and on the facing page an excerpt from Ovid's Art of Love. Never mind that the painting came from the wall of a house in Pompeii: that it dates from one hundred years later than Ovid's poem; that the couple is mythical, not human; and that Ovid was writing poetry for the elite whereas the viewer of this painting may have been illiterate. Yet with few exceptions studies of Roman so-called erotic art have assumed that Roman visual representations illustrated texts and that texts "document" Roman sexuality. Erudite studies of Latin words for sexual positions claim to find corroboration in wall paintings, lamps, even the coinlike spintriae—all considered without regard to their architectural contexts or dates.5

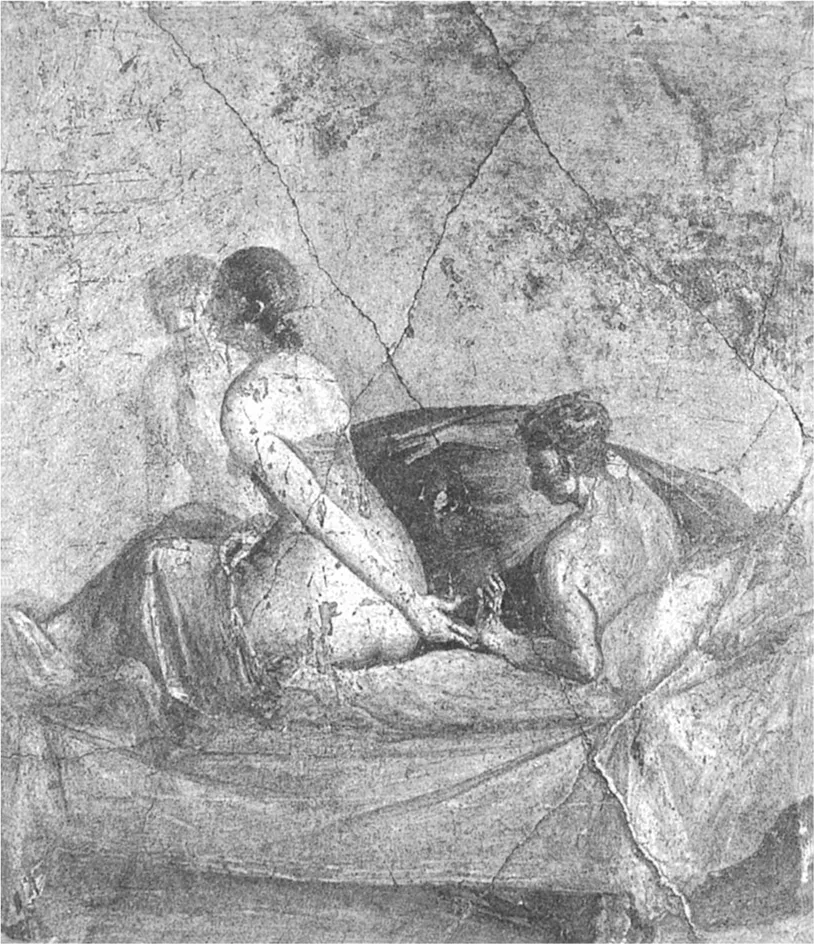

If we turn the tables and begin with the context of visual representations of lovemaking, surprising results emerge. We begin to understand how what seems to be erotic—by which I mean an image meant to stimulate a person sexually—had a totally different meaning for the ancient Roman viewer. A good case in point is the painting (dated A.D. 62-79) cut from a wall of the House of Caecilius Iucundus at Pompeii (fig. 1.1). Antonio Sogliano, who excavated this large residence in 1873, deemed it obscene and had it carted off to the infamous Pornographic Collection of the Naples Archaeological Museum. (To this day this room, filled with mosaics, wall paintings, and small objects, remains barred to the public.) Yet consideration of the original location of the picture, along with aspects of its imagery, indicates that it was the pride of the owner's house: it spelled "status," not "sex."

Figure 1.1 Pompeii, House of Caecilius Iucundus, peristyle, Couple on Bed with Servant. Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. 110569 (photo: Michael Larvey).

The owner was a freedman who had enlarged the house to make four dining rooms. The major dining area was the one located on the peristyle; it formed a suite with a luxurious kind of bedroom, one with two niches, immediately to its right. Our "erotic" painting occupied the important space on the peristyle itself between the doorways to these two rooms. Modern scholars, ignoring both the culture of Roman entertainment and the meaning of the picture itself, have assumed that the painting designated the bedroom as a place for a tryst after dining.6

We associate bedrooms with sleeping and sexual intimacy; the ancient Romans also used well-appointed bedrooms to entertain guests of a status equal to or higher than their own. The entire Roman house was a place of business; a guest's entrance into a fine cubiculum like this one depended entirely upon his status.7 This room is not, then, about "privacy"— a concept that does not exist in Roman language or thought—but about high status.

Examination of the painting itself shows that the painter was striving to create an image of upper-class luxury. There is a couple on a richly outfitted bed. The woman holds her hand behind her, whether to conceal her desire to touch the man or to locate him is not clear. He lifts his arm as though in entreaty, but she cannot see this gesture. A nice touch is the way his left hand curves up at the wrist, allowing the artist to show his virtuosity in depicting delicate fingers. The viewer sees these details but the woman does not, allowing the person who looks at this scene of lovemaking to understand the man's entreaty and the woman's hesitation in a way that the woman—and perhaps her lover also—cannot. In effect, the artist created these nuances of viewing to implicate the viewer as a voyeur. He also included the bedroom servant, the cubicularius, to underscore that this was not a poor man's bedroom. He even applied gold to highlight the opulence of fabrics and jewelry. These are all marks of wealth, luxury, and sophistication, similar to the paintings representing lovemaking from the famous villa of the early Augustan period found in Rome under the garden of the Farnesina.8

The painting was part of an extensive redecoration campaign with a pointed iconographical program.9 The adjacent dining room received a refined decorative scheme, including mythological pictures of the Judgment of Paris and Theseus Abandoning Ariadne.10 Someone entering the cubiculum would have seen relatively large figures at the center of the walls in front to the right and to the left. The room's principal image was a group of Mars and Venus with a figure of Cupid standing in the panel to the right. Bacchus presided over the right wall, on the left wall stood the muse Erato. It seems clear that the artist intended to expand the theme of lovemaking from the human to the divine by associating the vision of aristocratic dalliance in the peristyle panel with an image of passion stirring the quintessential divine lovers, Mars and Venus, in the main panel of the cubiculum. Wine and song, personified by Bacchus and Erato, muse of love poetry, furthered this iconography of amor...