eBook - ePub

Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods

Evolutionary, Developmental, and Cultural Perspectives

- 483 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the vast anthropological literature devoted to hunter-gatherer societies, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the place of hunter-gatherer children. Children often represent 40 percent of hunter-gatherer populations, thus nearly half the population is omitted from most hunter-gatherer ethnographies and research. This volume is designed to bridge the gap in our understanding of the daily lives, knowledge, and development of hunter-gatherer children.The twenty-six contributors to Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods use three general but complementary theoretical approaches--evolutionary, developmental, cultural--in their presentations of new and insightful ethnographic data. For instance, the authors employ these theoretical orientations to provide the first systematic studies of hunter-gatherer children's hunting, play, infant care by children, weaning and expressions of grief. The chapters focus on understanding the daily life experiences of children, and their views and feelings about their lives and cultural change. Chapters address some of the following questions: why does childhood exist, who cares for hunter-gatherer children, what are the characteristic features of hunter-gatherer children's development and what are the impacts of culture change on hunter-gatherer child care?The book is divided into five parts. The first section provides historical, theoretical and conceptual framework for the volume; the second section examines data to test competing hypotheses regarding why childhood is particularly long in humans; the third section expands on the second section by looking at who cares for hunter-gatherer children; the fourth section explores several developmental issues such as weaning, play and loss of loved ones; and, the final section examines the impact of sedentism and schools on hunter-gatherer children.This pioneering volume will help to stimulate further research and scholarship on hunter-gatherer childhoods, th

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods by Barry S. Hewlett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part V Culture Change and Future Research

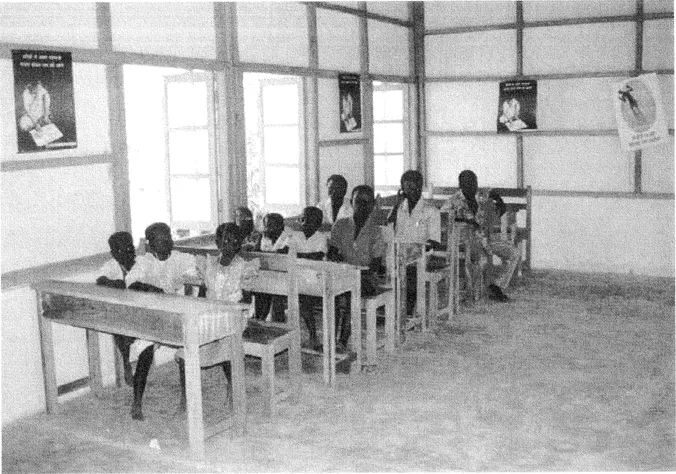

Photo 5 Ongee children in new school at Dugong Creek, Little Andaman Islands. Courtesy of V. Pandya

17 Infant Care among the Sedentarized Baka Hunter-Gatherers in Southeastern Cameroon

Ayako Hirasawa

Studies of infancy in hunter-gatherer societies1 were set in a fashion by Konner (1973, 1976) and his colleagues, who worked with the !Kung (Ju/’hoan) in the northern part of the Kalahari Desert in the late 1960s. Their work was conducted from an evolutionary framework where universal characterizations of infant development were investigated (see Konner, Chapter 2 in this volume). The number of studies of hunter-gatherer infants increased in the 1980s. Some researchers examined attachment theories in child development (e.g., Tronick et al. 1989; Hewlett 1991) while others examined how natural ecology influenced infant care (e.g., Blurton Jones et al. 1989). These studies questioned the universality of child development theories and pointed out how particular ecological and social settings contributed to diverse patterns of infant care. Issues of universal versus particularistic views of hunter-gatherer infancy persist (Konner, Chapter 2 in this volume). This chapter examines some of the universal versus particularistic questions discussed by Konner in Chapter 2 by providing a detailed ethnographic description of infant care among the Baka of southeastern Cameroon. In particular this chapter examines the impact of sedentarization and farming on infant care practices. The chapter takes a more “culturalist” approach, emphasizing social and cultural contexts (Harkness and Super 1980; Hatano and Takahashi 1997; Tanaka 1982; Yoshida 1984).

Many investigators have worked with the Baka since the 1940s. Baka are forest foragers and perform unique dances characterized by polyphonic song. In recent years, research on the Baka has focused on various topics, such as studies on their utilization of natural resources (Dounias 2001; Sato 1998, 2001), quantitative analysis of their dancing and singing performances (Bundo 2001; Joiris 1996,1997; Tsuru 1998), detailed description of children’s play (Kamei, Chapter 16 in this volume), studies of social interactions (Kimura 2001), and linguistic reconstruction of their historical prehistory (Bahuchet 1993). Furthermore, recent studies have examined the impact of culture change; Kamei (2001) has examined how Baka have responded to schooling and Hewlett (2000) has examined how governments and nongovernmental organizations view and provide “development” projects for Baka. Few descriptions of Baka infancy exist, systematic behavioral studies on Baka infants have never been undertaken, and no study to date has examined the impact of sedentarization and farming on forager infant care. This study is an ethnographic and theoretical contribution to existing studies of forager infants. Ethnographically it describes the details of Baka infant care. Observational methods were also similar to previous forager infant studies so comparisons of infancy in other foragers are also evaluated. Theoretically, the chapter addresses issues of universal versus particularistic nature of forager infant care.

Childrearing serves the universal purpose of securing the survival and growth of biologically and socially immature individuals, but childrearing practices vary from society to society. This diversity in infant care practices can be explained in terms of various factors, including the natural environment, subsistence activities, social structure, interpretation of the world, and societal history. Infant care is one of the phenomena through which the prominent features of a society emerge. This chapter attempts to home in on the Baka society and its people through their infant care practices.

Sedentarized Baka Hunter-Gatherers

I conducted field research in the sub village of Mbeson, a part of Landjoué village, Yokadouma District, Bumba-Ngoko Division, in East Province of the Republic of Cameroon. I stayed there for about ten months, from September 2000 to June 2001.

Mbeson is located alongside the logging load penetrating the tropical forest. The nearest town is Yokadouma, 17 kilometers east of Mbeson. People from Mbeson sometimes stay in Yokadouma for several days to buy daily household staples or to go to the hospital. Mbeson is inhabited mostly by the Baka and the Bombong. The Baka are one of the ethnic groups that have been referred to as Pygmies. They speak an Oubanguiah language, and live in the tropical rain forests that extend from northwestern Congo to southeastern Cameroon. The Baka population is estimated to be 33,000 (Cavalli-Sforza 1986). The Bombong are Bantu-speaking farmers who live in southeastern Cameroon. In September 2000, the population of Mbeson numbered 235 people, of which 153 (65.1 percent) were Baka.

According to Baka and Bombong elders, the first immigrants were a family of Bombong, who arrived in the late 1940s from Central Landjoué, 1 kilometer west of Mbeson, seeking a larger area to cultivate. At that time, the Baka led a foraging lifestyle in the forest, living in much smaller residential groups than now. In the process of interviewing women in Mbeson about their childbirth experiences, I found that until the 1950s their children had been born in various areas in East Province in abandoned camps, and some of them had been born in different places, which suggests that the Baka used to move around in the forest, changing residence frequently

In the 1950s, some of the Baka near Mbeson started working for the Bombong in order to procure agricultural products. Soon after, they established semisedentary camps in the forest near Mbeson and commenced small-scale self-sufficient cultivation,2 partly retaining their foraging life. From the late 1950s to the early 1960s, the colonial administration issued an order to the chiefs around Yokadouma, appealing to the Baka to settle along the road. As a result of the chiefs’ efforts, two residential groups, familiar with the Bombong, settled down to live alongside the Bombong in the early 1960s. In the 1970s, after sedentarization, the Baka began growing cacao as a cash crop, as their neighbors did. They still continue many kinds of activities, such as hunting, gathering, and fish-bailing in the forest. They also move into forest camps for several weeks during the agricultural off-season.

However, the cultivation of subsistence and cash crops quantitatively provides the most important part of their livelihood and the major part of their diet. In addition to working in their own fields, the Baka often provide the Bombong with agricultural labor to procure cash. This helps the Bombong to maintain their cacao fields because of the labor shortage existing because many young Bombong leave the village for school and to work in towns or for logging companies. This relationship between the Baka and the Bombong partly promotes a sedentary life and a dependency on cultivation among the Baka.

Since their livelihood has shifted from hunting and gathering to agriculture, other social dimensions also seem to be changing. For instance fission and fusion of the residential groups, which is regarded as a regular feature of hunter-gatherer societies, does not happen frequently in Mbeson. The membership of Mbeson is fairly stable. Today, most of the Baka men possess cacao fields, which require substantial labor to maintain; therefore, they are somewhat reluctant to migrate to other villages. It is also noteworthy that I did not observe extensive daily food sharing and cooperation, which is said to enhance close relationships among the constant members of hunter-gatherer societies. Among the Baka in Mbeson, the basic unit of production and consumption is the household based on the nuclear family, although relatives who shared experiences before sedentarization are still very familiar to one another. I did not discern a sense of unity binding the entire village. It appeared to me that the Baka lifestyle in Mbeson is no longer identical to that of hunter-gatherers, but is quite similar to that of the neighboring Bombong. During the initial phases of my research, I expected that Baka infant care would be dramatically different from that described among other hunter-gatherers.

Methods

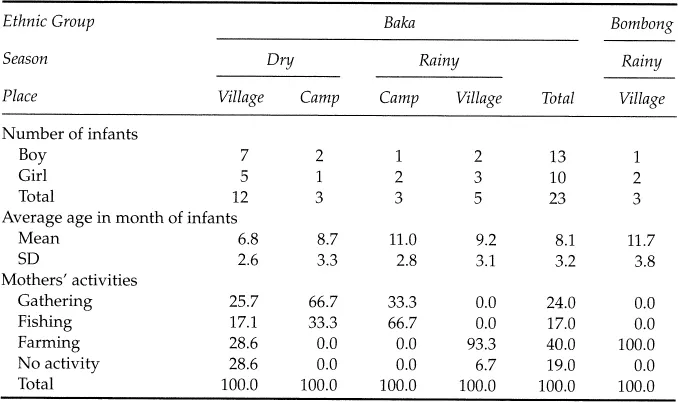

I employed the following two observational methods to identify characteristics of infant care among the Baka. One was instantaneous sampling, in which each focal infant was followed and observed for three days. The three-day sampling series was conducted in the village and the forest camp, during the rainy and dry season, respectively, in four settings in all. Daytime (6:30–18:30) was divided into 12 one-hour time blocks, during which a 30-minute observation was conducted. The following parameters were recorded every 5 minutes during the 30-minute observation: (1) behaviors of the focal infant, (2) behaviors of the mother, (3) behaviors of the most proximal individual, (4) distance between the focal infant and his/her mother, and (5) distance between the focal infant and the most proximal individual. I followed a total of twenty-three Baka infants ranging in age from 1 to 13 months. For comparison, I used the same method to observe three Bombong infants in the village during the rainy season, when both the Baka and the Bombong were exclusively engaged in cultivation. Details on the focal infants’ and mothers’ activities in instantaneous sampling are summarized in Table 17.1.

The other method I employed was focal continuous sampling, which was conducted the day following instantaneous sampling. Focal infants, both the Baka and the Bombong, were traced continuously for 12 hours from 6:30 to 18:30, and the following parameters were recorded: (1) time of nursing, (2) context of nursing.

In the following sections, I describe Baka infant care, focusing on four issues, which are common to most studies of hunter-gatherer infants: (1) Who cares for infants? (2) How often do mothers nurse the infants? (3) How do caregivers stimulate the infants? (4) How proximal are infants to caregivers?

Children as Secondary Caregivers

As in many other societies, the primary caregivers of infants among the Baka are the mothers. The instantaneous sampling showed that infants’ mothers are the most proximal individuals for 59.3 percent of the daytime on average.3 Other individuals cared for the infants for the remaining five daylight hours when the mothers were engaged in subsistence activities including food preparation and collecting water. On average, 5.3 people besides the mother were observed as caregivers of the infant during the day.

Table 17.1 Details on Instantaneous Sampling

1) the rate of mothers’ activities means how many days the mothers are engaged in each activity during observational season.

2) The average rate of mothers’ activities does not reflect the actual rate of subsistence activities through one year.

3) When the mother is engaged in more than two kinds of subsistence activities, the longest one is employed as the main activity on that day.

Hewlett pointed out that multiple or allomaternal caretaking is one of the common features of Pygmy societies (1996). The highest level of multiple caretaking is reported among the Efé. According to Tronick et al. (1987), Efé multiple caretaking is characterized as follows: (1) 14.2 different people on average had physical contact with the infant during their observation, (2) the infant was often nursed by individuals other than the mother, and (3) the infant was transferred from caregiver to caregiver about eight times per hour. Tronick et al. suggest that this parenting system helps Efé infants acquire culturally appropriate behaviors, such as cooperation, sharing, and group identification, by associating with many caregivers in the residential group. In regard to the high transfer rate, they maintain that it is adaptive for increasing infants’ heat production in a cool forest environment.4

Among the Aka, paternal involvement in infant care is much higher than in any other known societies (Hewlett 1991b). Aka fathers show a strong intimacy and affection toward their infants. They are likely to hug and kiss them more frequently than the mothers. Hewlett identified their technique of net-hunting and the relationship between husbands and wives as some of the influential factors that have led to the evolution of this practice. Aka men and women cooperatively engage in net-hunting, and their relationships are very egalitarian in other social dimensions. In this society, infant care...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- I THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL ISSUES

- II WHY DOES CHILDHOOD EXIST?

- III WHO CARES FOR HUNTER-GATHERER CHILDREN?

- IV SOCIAL, EMOTIONAL, COGNITIVE, AND MOTOR DEVELOPMENT

- V CULTURE CHANGE AND FUTURE RESEARCH

- References

- Index