![]()

Part I

Pre-Classical Thought

Introduction

It is a widely held, and probably substantially correct, view that the emergence and development of modern economic thought was correlative with the emergence of a commercial, eventually industrial, capitalist market economy. It is this economic system, especially as it arose in Western Europe in the eighteenth century, that economics attempts to describe, interpret, and explain, as well as to justify. This economic thought was both positive and normative, that is, it combined efforts to objectively describe and explain with those to justify and/or to prescribe (such as policy). As a positive, scientific discipline, it combined two modes of thought: (1) empirical observation, dependent upon some more or less implicit theoretical or interpretive schema, and (2) logical analysis of the relationships between variables, dependent upon some more or less conscious generalization of interpreted observations.

Prior to this time, speaking generally, there were markets and market relationships but not market economies as the latter came to be understood after roughly the eighteenth century. While modern economic theory did not exist, thinkers of various types did speculate about a set of more or less clearly identified “economic” topics, such as trade, value, money, production, and so on. These speculations are found in documents emanating from the ancient civilizations, such as Sumeria, Babylonia, Assyria, Egypt, Persia, Israel, and the Hittite empire. Some of these documents are literary or historical; others are legal; still others arose out of business and family matters; and others involved speculation about current and/or perennial events and problems. It is clear that economic activity, especially that having to do with trade, both local and between distant lands, was engaged in by households and specialized enterprises, and gave rise to various forms of economic “analysis.”

These documents seem not to have contained anything like what we now recognize as theoretical or empirical economics. But they do indicate several important concerns, centering on the general problem of the organization and control of economic activity: problems of class and of hierarchy versus equality, problems of continuity versus change of existing arrangements, problems of reconciling interpersonal conflicts of interest, problems of the nature and place of the institution of private property in the social structure, problems of the distributions of income and taxes, and so on, all interrelated. Much of the speculation related to current issues rather than to abstract generalizations, but the latter are not absent.

Early economic thought had two other characteristics: One was the mythopoeic nature of description and explanation: explication through the creation of stories involving either the gods or, eventually, God, or an anthropomorphic characterization of nature as involving spirits and transcendental forces. The other was the subordination of economic thinking to theology and organized religion and, especially, the superimposition of a system of morals upon economic (and other forms of) activity. The former remains in the form of the concept of the “invisible hand”; the latter, in the felt need for the social control of both individual economic activity and the organization of markets. The latter also gave this analysis more of a normative cast than one finds in much of modern economics.

“Modern” philosophy in the West traces back to the Greeks during the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Mythopoetry does not disappear but, one might sense, reaches its highest levels of sophistication, and, especially, existing alongside of self-conscious and self-reflective philosophical inquiry, the latter becoming increasingly independent—though not without tension and conflict. The development of philosophy is facilitated and motivated by (1) the postulation of the existence of principles of an intellectual order in the universe (in nature and in society), (2) the growing belief in the opportunity accorded by God to study the nature of things without such activity being deemed an intrusion upon the domain of God, and inter alia (3) the development of principles of observation, logic, and epistemology.

In the eighth century BC, Hesiod wrote several works, one of which, Ode to Work (or Works and Days), identified the role of hard, honest labor in production and the studied approach to husbandry and farming, the latter couched in terms of proceeding in the manner desired by deified forces of nature, including the seasons. This work was cited three centuries later by Plato and Aristotle. One of their contemporaries was Xenophon (430–355 BC), whose Oeconomicus dealt with household management (most production was undertaken by households) and with analyses of the division of labor, money, and the responsibilities of the wealthy. Xenophon's Revenue of Athens was a brilliant analysis of the means that could be employed by the organized city-state to increase both the prosperity of the people and the revenues of their government, an analysis combined with the injunction, once the program of measures of economic development had been worked out, to consult the oracles of Dodona and Delphi if such a program was indeed going to be advantageous.

But it is with Plato (427–347 BC), notably in his Republic and The Laws, and with Aristotle (384–322 BC), in his Politics and Nichomachean Ethics, that more elaborate and more sophisticated economic analysis takes place. Both Plato and Aristotle were concerned with (1) aspects of the relation of knowledge to social action; (2) topics of political economy, such as the nature and implications of “justice” for the organization and control of the economy, including issues of private property versus communism and/or its social control; and (3) more technical topics of economics, such as self-sufficiency versus trade, the consequences of specialization and division of labor (including their relation to trade), the desirable-necessary location of the city-state, the nature and role of exchange, the roles of money and money demand, interest on loans, the question of population, prices and price levels, and the meaning and source of “value.” Their discussions of these topics reflect the social (read: class) organization of Athens, the deep philosophical positions they held on a variety of topics, the economic development of Athens and its trading partners, and how they worked out solutions to serious, perennial problems of social order. In terms of the canon of Western economic thinking, economic analysis largely disappeared for roughly a millennium-and-a-half subsequent to the death of Aristotle, not to reappear in a significant way until the scholastic writers beginning in the thirteenth century AD.

The readings that follow in this section trace the development of economic thought from the Greeks through the late eighteenth century. Along the way, the reader will be introduced to classic writings in scholasticism, mercantilism, and physiocracy, as well as to works that mark a turn in economic thinking toward a more systematic, and some would say scientific, method of analysis. While economics, throughout this period, was primarily considered to be, and analyzed from the perspective of, larger systems of social and philosophical thought, the economic system increasingly came to be recognized as a sphere that embodied its own particular set of laws, worthy of analysis in its own right. The reader will also notice an increasing recognition over this period of the interdependent nature of economic phenomena and thus the tendency of the authors to increasingly treat the economic system as an interrelated whole as opposed to engaging in piecemeal analysis of particular aspects of economic activity.

References and Further Reading

Blaug, Mark, ed. (1991) Pre-Classical Economists, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hutchison, Terence (1988) Before Adam Smith: The Emergence of Political Economy, 1662–1776, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Letwin, William (1964) The Origins of Scientific Economics, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.

Lowry, S. Todd, ed. (1987) Pre-Classical Economic Thought: From the Greeks to the Scottish Enlightenment, Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Rothbard, Murray (1995) Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Spengler, Joseph J. (1980) Origins of Economic Thought and Justice, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

![]()

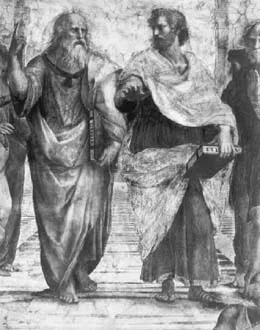

Aristotle with Plato, by courtesy of Corbis, www.corbis.com.

Aristotle was born in Stagira and spent some twenty years studying under the tutelage of Plato in Athens. After a number of years of travel and serving as tutor to the young man who would later become Alexander the Great, Aristotle returned to Athens and established his own school, the Lyceum, in 335 BC.

The works of Aristotle span virtually the entire breadth of human knowledge—logic, epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, the natural sciences, rhetoric, politics, and aesthetics. While only a small fraction of his writings deal with economics, he did see matters economic as an important aspect of the social fabric and thus as necessary elements of a larger social–philosophical system of thought. Aristotle's writings had a profound influence on Aquinas and, through Aquinas, on subsequent scholastic thinking. Indeed, Aristotle's influence continues to be present in modern economic theory.

In the excerpts from Aristotle's Politics and Ethics provided below, we are introduced to his theories of the natural division of labor within society, household management (œconomicus) and wealth acquisition (chrematistics), private property versus communal property, and of the exchange process. The reader may wish to take particular note of the “reciprocal needs” basis of Aristotle's division of labor, his view that wealth acquisition is “unnatural” because it knows no natural limits, his strong defense of private property (as against his teacher, Plato), and his theory of reciprocity in exchange.

References and Further Reading

Finley, M.I. (1970) “Aristotle and Economic Analysis,” Past and Present 47 (May): 3–25.

—— (1973) The Ancient Economy, Berkeley: University of California Press.

—— (1987) “Aristotle,” in John Eatwell, Murray Milgate, and Peter Newman (eds.), The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Vol. 1, London: Macmillan, 112–13.

Gordon, Barry (1975) Economic Analysis Before Adam Smith: Hesiod to Lessius, New York: Barnes and Noble.

Laistner, M.L.W. (1923) Greek Economics: Introduction and Translation, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.

Langholm, Odd (1979) Price and Value Theory in the Aristotelian Tradition, Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.

—— (1983) Wealth and Money in the Aristotelian Tradition, Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.

—— (1984) The Aristotelian Analysis of Usury, Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.

Lowry, S. Todd (1969) “Aristotle's Mathematical Analysis of Exchange,” History of Political Economy 1 (Spring): 44–66.

—— (1979) “Recent Literature on Ancient Greek Economic Thought,” Journal of Economic Literature 17: 65–86.

—— (1987) The Archaeology of Economic Ideas: The Greek Classical Tradition, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Soudek, Josef (1952) “Aristotle's Theory of Exchange: An Enquiry into the Origin of Economic Analysis,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96: 45–75.

Spengler, Joseph J. (1955) “Aristotle on Economic Imputation and Related Matters,” Southern Economic Journal 21 (April): 371–89.

—— (1980) Origins of Economic Thought and Justice, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Worland, Stephen T. (1984) “Aristotle and the Neoclassical Tradition: The Shifting Ground of Complementarity,” History of Political Economy 16: 107–34.

Politics*

Book I

Part I

Every state is a community of some kind, and every community is established with a view to some good; for mankind always act in order to obtain that which they think good. But, if all communities aim at some good, the state or political community, which is the highest of all, and which embraces all the rest, aims at good in a greater degree than any other, and at the highest good.

Some people think that the qualifications of a statesman, king, householder, and master are the same, and that they differ, not in kind, but only in the number of their subjects. For example, the ruler over a few is called a master; over more, the manager of a household; over a still larger number, a statesman or king, as if there were no difference between a great household and a small state. The distinction which is made between the king and the statesman is as follows: When the government is personal, the ruler is a king; when, according to the rules of the political science, the citizens rule and are ruled in turn, then he is called a statesman.

But all this is a mistake; for governments differ in kind, as will be evident to any one who considers the matter according to the method which has hitherto guided us. As in other departments of science, so in politics, the compound should always be resolved into the simple elements or least parts of the whole. We must therefore look at the elements of which the state is composed, in order that we may see in what the different kinds of rule differ from one another, and whether any scientific result can be attained about each one of them.

Part II

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin, whether a state or anything else, will obtain the clearest view of them. In the first place there must be a union of those who cannot exist without each other; namely, of male and female, that the race may continue (and this is a union which is formed, not of deliberate purpose, but because, in common with other animals and with plants, mankind have a natural desire to leave behind them an image of themselves), and of natural ruler and subject, that both may be preserved. For that which can foresee by the exercise of mind is by nature intended to be lord and master, and that which can with its body give effect to such foresight is a subject, and by nature a slave; hence master and slave have the same interest. Now nature has distinguished between the female and the slave. For she is not niggardly, like the smith who fashions the Delphian knife for many uses; she makes each thing for a single use, and every instrument is best made when intended for one and not for many uses. But among barbarians no disti...