- 462 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

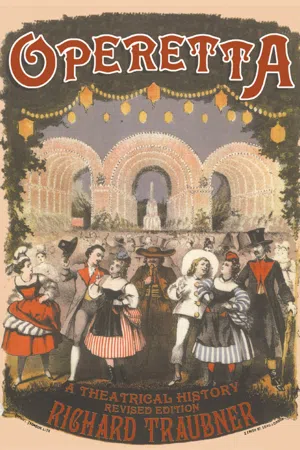

"Operetta: A Theatrical History" is considered the classic history of this important musical theater form. Traubner's book, first published in 1983, is still recognized as the key history of the people and productions that made operetta a worldwide phenomenon. Beginning in mid-19th century Europe, the book covers all of the key developments in the form, including the landmark works by Strauss and his followers, Gilbert & Sullivan, Franz Lehar, Rudolf Friml, Victor Herbert, and many more. The book perfectly captures the champagne-and-ballroom atmosphere of the greatest works in the genre. It will appeal to all fans of musical theatre history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Operetta by Richard Traubner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicBROADWAY

THE GENUS Broadway operetta, as distinct from the nineteenth-century comic opera, had two major influences: Victor Herbert and the Viennese operettas of the Silver Era. Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml were the leading composers of the late teens and 1920s, and both had middle-European backgrounds. Though much of their work in the teens was frankly, requisitely imitative of Herbert, their operettas of the ’20s were as spectacularly romantic as the gushing costume operettas of Lehár, if not more so. The uniformed male choruses that Herbert had held over from the older comic operas were retained by Friml and Romberg, and given similarly stirring marches. Perhaps influenced by the close-up intimacy and spectacular passion of the hugely popular silent screen, operettas were forced to be increasingly romantic and full-blooded, rather than satiric or comic.

What is astounding about the ’20s is that while these hot-blooded romantic operettas were being created and consumed, the same years saw the birth of the fast, dancing, jazz musical comedies of Gershwin, Youmans, and other composers, as well as excellent revues, both spectacular and intimate, and also attempts to modernize operetta into something almost as zippy as musical comedy. It was truly the Golden Age of the American musical theatre, and one that did not really end in 1929. The potent romantic and sentimental elements that had made The Student Prince and Show Boat such superb operettas were simply streamlined in the 1940s and transformed into the “musical play,” a euphemism for romantic operetta. The main differences between the 1920s and the 1940s operetta involved the replacement of passion with compassion and psychology, cleverer segues into songs that had to do more sophisticatedly with character and plot than before, an attempt to use the comedian and soubrette more effectively in the story, and, most importantly, the use of ballet for story or mood purposes, sometimes replacing the central finales altogether. Some acclaimed modern musical plays are very apparently and decisively operettas, though critics do not care to admit that they are. Recently revived on Broadway, shows like Oklahoma!, Brigadoon, The King and I, West Side Story, My Fair Lady, and Camelot are all to varying degrees romantic operettas, and there are those who would consider The Most Happy Fella and Porgy and Bess operettas as well, if not American operas. There are several other classic “musical plays” that are so much operettas that there seems to be a slight hesitation in reviving them, in spite of their magnificent scores: Carousel and South Pacific are two examples. The latter was however recalled to life in 1987, with a recording, a New York City Opera mounting, a popular revival at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre, and a touring edition with Robert Goulet.

(Charles) Rudolf Friml (1879–1972) was born in Prague and was a star music pupil at its Conservatory, which he entered at the age of fifteen. In Friml’s last year there, Antonin Dvořák was one of his teachers. His talents as a pianist were for many years employed by Jan Kubelik, the violinist, with whom he first visited the United States in 1901. During these years, many of Friml’s piano compositions were published. By 1904, he arranged his own tour of the United States, including in his repertoire his own Piano Concerto in B. In 1906 he settled in New York.

His piano works apparently attracted the attention of music publishers Max Dreyfus and Rudolph Schirmer, who reportedly suggested Friml as a replacement for Victor Herbert as the composer for Arthur Hammerstein’s production of The Firefly (Lyric, 2 December 1912). Emma Trentini and Herbert had quarreled after Naughty Marietta, and Hammerstein quickly had to find a new composer for the Otto Hauerbach (Harbach) libretto. Miss Trentini played an Italian street singer (of course!) who travels to Bermuda as a cabin boy and ends up a famous opera star. The “cabin boy,” Tony, got to sing “Giannina Mia” and his alter ego, Nina, thrilled audiences with the title song, “(Love is Like a) Firefly.” Another song hit was “Sympathy.” The Broadway run was 120 performances, and there were reprises in later seasons. The 1937 MGM film jettisoned the Hauerbach plot and substituted one by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, with Ogden Nash that concerned a female spy in Spain during the Napoleonic era. Jeanette MacDonald sparkled in Oliver Marsh’s camera setups. The big song hit from the film was “The Donkey Serenade,” an adaptation of a 1920 piano piece. Sung by Allan Jones, it became his trademark.

High Jinks (Lyric, 10 December 1913) was a lighter story, concerning a perfume which made its wearers giddy. “Something Seems a Tingle-ing-eling” was the best song (later sung by Cyril Ritchard in his last Broadway appearance in a revue). This ran longer than The Firefly and was reproduced in London (Adelphi, 24 August 1916) with an interpolation by Jerome Kern, the wonderful “It Isn’t My Fault,” sung by W.H.Berry and Marie Blanche. The London run nearly doubled Broadway’s. Katinka was a return to the more romantic style of The Firefly and was popular both in New York (44th Street, 23 December 1915), with Franklin Arcade and Adele Rowland, and in London (Shaftesbury, 30 August 1923), with Joseph Coyne and Binnie Hale. Hauerbach’s libretto switched from Russia to Austria (France, in the British production), and Friml’s score had a number of delectable melodies: the sumptous “Allah’s Holiday” showed the path that led to Rose-Marie’s “Indian Love Call.” You’re in Love (1917), Sometime (1918), Glorianna—no relation to Britten’s opera—(1918), Tumble In (1919), The Little Whopper (1919), and June Love (1921) were not musically in the same category as The Firefly or Katinka, but Sometime had a startling cast that contained Ed Wynn, Francine Larrimore, and Mae West as a vamp. The Blue Kitten (Selwyn, 13 January 1922) further confirmed the musical-comedy bent Friml seemed to be pursuing: he even contributed to the Ziegfeld Follies that season.

Cinders (1923) was unnotable, and it would have seemed that Friml’s career was at a standstill. Until the second of September 1924, when the Imperial Theatre presented Rose-Marie to an enraptured audience. Arthur Hammerstein had wanted an ice spectacular, but this became unfeasible. Retaining a Canadian setting, however, the producer had Hauerbach (now Harbach) and Oscar Hammerstein II map out the fundamentally serious love story of the Rockies concerning a singer and her lover, implicated in the murder of an Indian, Black Eagle. This added a bit of excitement to what was otherwise a fairly common Leháresque plot of impossible love in some strange place—Endlich Allein had a mountain plot as well. But Rose-Marie rather cleverly managed to merge the vivacious rhythms of contemporary Broadway with the dreamy Lehár; even the most romantic songs had a dash and verve that had hitherto been lacking.

The original Imperial Theatre programme declined to list the songs, rather pretentiously stating: “The musical numbers of this play are such an integral part of the action that we do not think we should list them as separate episodes.” (In London, however, the songs were listed separately.) Certainly, there was a cinematic flavor to the proceedings, with constant use of mélodrame, perhaps in an attempt to give spectacular scope to the operetta to compete with the motion picture, which by this time had reached new plateaus of elaborateness in films like The Thief of Bagdad. Rose-Marie also had general and specific screen antecedents. Between 1921 and 1923 there were no less than forty feature films with Canadian Northwest Mounted Police plots, and one of them, Tiger Rose (1923, based on a 1917 stage melodrama), had a plot vaguely similar to the following season’s Rose-Marie.

The operetta had two male singing leads: Jim Kenyon, with whom RoseMarie is in love, and Sergeant Malone of the RCMP. Plus the buffo part (instrumental in unraveling the murder) of Hard-Boiled Herman. In New York, the classically trained English actor, Dennis King, originated the part of Jim, with Arthur Deagon as Malone and William Kent as Herman. In London, Derek Oldham, of D’Oyly Carte fame, was Jim, John Dunsmure was Malone, and Billy Merson (later Nelson Keys) was Herman. On the distaff side, the Metropolitan Opera soprano Mary Ellis was the world’s first Rose-Marie, while Edith Day, the American singer who had conquered London in Tierney’s Irene, played the part at Drury Lane (20 March 1925).

Rose-Marie was not the first operetta to involve a murder. Offenbach’s first full-length operetta, Orphée aux Enfers (1858), had Eurydice killed in the first act by Pluton. But Rose-Marie, building on the turn-of-the-century libretti furnished for Victor Herbert, provided the “serious” romantic mold set in some exotic locale that would become stylish in the 1920s. The plots might deal with a doomed love (The Student Prince), or political upheaval (The Vagabond King, The New Moon), or even racial strain (Show Boat, Golden Dawn), but there was definitely a new effort to avoid the trivialities of musical comedy and the purely romantic escapades of royalty and disguised-royalty that still dominated the Central European operetta in the ’20s.

This is not to say that operetta libretti suddenly became serious. Most of them were still the familiar drivel, and the quality of the lyrics on the whole showed no improvement. But there was definitely a vibrancy and a stoutheartedness about these shows that proved immensely popular, as did the exoticism and glamor found necessary to rival the spectacle offered to the public so inexpensively any week on celluloid.

And it was in its spectacle that Rose-Marie proved so influential. One great attraction of the first productions was the “Totem Tom-Tom” number near the end of Act I. The words were arrant nonsense, with silly rhymes that harked back to the Geisha era, and the song—like so many memorable production numbers—advanced the plot not one whit. But when one hundred dancers appeared in formation dressed as totem poles (the young Anna Neagle was one at Drury Lane), the effect was quite spectacular. And it was truly an operetta a grand spectacle, with ten elaborate scenes to suit Parisian tastes. The Paris production (Mogador, 9 April 1927) was, incredibly, the longest-running of all (1,250 performances), with more revivals in that city than anywhere else. The French version was led by Robert Burnier (Jim), Felix Oudart (Malone), and Cloe Vidiane (Rose-Marie). Drury Lane saw 851 performances, and without a ticket-broker deal prior to the première, as the agencies were unconvinced the show would be a hit. The Imperial run was the least impressive—only 557 showings—but it made more money than any Broadway musical play until Oklahoma! in 1943, and it made Oscar Hammerstein II a millionaire in seven months. Moreover, Rose-Marie appeared all over the world to great acclaim, and was still a staple of repertoires in Eastern Europe, particularly in the Soviet Union, where it was often used for mildly anti-American jokes, as in a production at Leningrad’s Musical Comedy Theatre.

Rose-Marie was King George V’s favorite show—he saw it no less than three times during its original Drury Lane run, and again on revival. It was so popular that it was decided not to hold up the first film version in order to wait for the perfection of sound recording. MGM released Rose-Marie in 1928, with Joan Crawford in the title role, and with a somewhat altered plot, but with a musical score based on Friml and Stothart, though without actual singing. Herbert Stothart let himself go on the MGM remake in 1936; he also let most of Friml’s score go as well, to be replaced by items ranging from the “St. Louis Blues” to scenes from Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette and Puccini’s Tosca. Nevertheless, W.S. Van Dyke’s Rose-Marie remains, to many, the most characteristic of the Jeanette MacDonald-Nelson Eddy epics. The mountain scenes, filmed at Lake Tahoe, gave a breadth to “Totem Tom-Tom” and the “Indian Love Call” that was obviously impossible to achieve on the stage. Unfortunately, songs like “Door of My Dreams,” “Pretty Things,” and “Minuet of the Minute,” all of which would have been perfect material for Miss MacDonald, were not used. A sensible plot emendation had the Mountie sergeant becoming Rose-Marie’s swain, making the story less complicated. Mervyn LeRoy’s 1954 version had several things going for it: CinemaScope, Eastman Color, Bert Lahr (as the “Mountie Who Never Got His Man”), and Howard Keel, reverting to the original conception of the Mountie sergeant who doesn’t get his girl.

Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy in the famous MGM film version of Friml-Stothart’s Rose Marie (1936). Even today, “MacDonald and Eddy” mean operetta to many Americans. MGM.

It would have been nice to report that the next Friml hit was also a resounding success in Paris, but The Vagabond King, based on the romanticized exploits of François Villon, was never seen there. Nevertheless, it proved dramatically popular in the English-speaking world. Based on Justin Huntly McCarthy’s If I Were King, which had been a vehicle for E.H.Sothern from 1901 in the United States, and for Sir George Alexander from the next year in the United Kingdom, the story took considerable liberties with history, and the characters were musical-comedy-ized to an extent. But the plot was sufficiently romantic and robust to attract Friml and W.H.Post and Brian Hooker (the librettists). Structurally, it was similar to Rose-Marie in its use of a wanton rival for the attention of the hero. In the former, the Indian girl Wanda; in The Vagabond King, the prostitute Huguette.

Producer Russell Janney’s “New Spectacular Musical Play” at the Casino (21 September 1925) was carefully tailored for Dennis King, whose Shakespearean training and thrilling singing voice could finally be used at the same time. Opposite King was Carolyn Thompson as Katherine de Vaucelles, Jane Carroll as Huguette. Max Figman played King Louis XI and also staged the operetta for its producer. The Casino registered 511 performances. In London, the tally at the Winter Garden (19 April 1927) reached 480. Leading the London cast were Derek Oldham and Winnie Melville (who were actually husband and wife) as the lovers, while Norah Blaney and H.A.Saintsbury were streetwalker and monarch, respectively. The operetta was filmed in 1930 with King repeating his stage role and Jeanette MacDonald as Katherine, directed by Ludwig Berger. There was a dull remake in 1956.

The Vagabond King is arguably Friml’s best score. In order of their appearance, the better songs are: “Love for Sale,” the drinking song, “A Flagon of Wine,” the “Song of the Vagabonds,” “Some Day,” “Only a Rose,” “Tomorrow,” the “Huguette Waltz,” and “Love Me To-night.” The comic numbers were only marginally less successful, the “Serenade” trio “Lullaby! Plim-Plum” being quite likable, and there are any number of other captivating marches and flourishes. The reprises—and there were many—were not discomfiting: one could listen to “Only a Rose” and “And to Hell with Burgundy!” over and over. Today, the medievalistic dialogue and idiotic jokes would seem contrived, but the force and amorousness of the songs are not dated. Major revivals of The Vagabond King have been attempted outside of New York, but a truly thrilling leading man would be required to sell the show on Broadway, along with extensive dialogue revisions.

Both The Wild Rose (1926) and The White Eagle (1927) were failures. The first concerned Americans in Monte Carlo, the second was set in Indian territory, a musical version of The Squaw Man, the 1905 play that had been the basis of a famous 1913 Cecil B.De Mille film. Too much Americana probably convinced Friml that a return to European romance was in order, and to Alexandre Dumas père, at that. The Three Musketeers (Lyric, 13 March 1928) was a Ziegfeld pro-duction, with book by William Anthony McGuire, sets by Joseph Urban, glorious costumes by Jack Harkrider, a leading Ziegfeld costumier, and lyrics by P.G.Wodehouse and Clifford Grey. McGuire had difficulty supplying the script in time, and so insisted on having the entire company see the 1921 Fred Niblo/ Douglas Fairbanks film of The Three Musketeers prior to the last rehearsals so he could finish his work. McGuire also had to stage the production, and rehearsals were far from amicable due to the intense rivalry of Dennis King (as D’Artagnan) and Vivienne Segal (as Constance). Reginald Owen was Richelieu. The musketeers were Douglass Dumbrille (Athos), Detmar Poppen (Porthos), and Joseph Macaulay (Aramis).

Surprisingly, Friml’s melodious score and the time-proved plot did not add up to a very long run: only 318 performances in New York and 240 in London (Drury Lane, 28 March 1930), where Dennis King repeated his part opposite Adrienne Brune (Constance), Webster Booth (Buckingham), Lilian Davies (Queen Anne), and Arthur Wontner—a well-known Sherlock Holmes impersonator (Richelieu). Raymond Newell, as Aramis, stopped the show cold with his rendition of “Ma Belle,” just as Joseph Macaulay had done on Broadway. But King stole all hearts. “From the moment when D’Artagnan arrived at the Inn of the Jolly Miller on a white horse painted to represent emaciation, and the young Gascon clad in rags leapt from the steed, Dennis King was the favorite with the audience,” reported the critic of the Daily News.

The score to The Three Musketeers nearly rivaled that for The Vagabond King, even if some of the songs were very patently suggested by those from the earlier show: “One Kiss” was alarmingly similar to “Love Me To-night,” for one example. But the swaggering anthems and marches were so excellent that they swept almost all else aside and easily conquered audiences: “Gascony,” “My Sword and I,” “March of the Musketeers” being the principal examples. Dennis King’s swashbuckling was admired in both song and action. During the London run a bit of D’Artagnan’s épée broke during a particularly active fight and sailed out into the audience, landing on a lady’s lap. She took her souvenir home, and before the nervous management thought they would receive a lawsuit, the lady had written a kind letter inquiring whether she could keep her memento.

Luana (Hammerstein, 17 September 1930) was originally intended as a film musical of the Richard Walton Tully play The Bird of Paradise (which was eventually filmed as a straight romance in 1932 with Dolores del Rio and Joel McCrea, and remade in 1951). With the famous theme-song for Ramona in the Del Rio film proving such a potent advertisement, one can almost hear Hollywood asking Friml for “Luana.” But the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Preface to the Revised Edition

- Overture

- Beginners, Please!

- The Emperor of Operetta

- Post-1870 Paris

- Vienna Gold

- The School of Strauss II

- The Savoy Tradition

- The Edwardesian Era

- Fin De Siècle

- The Merry Widow and Her Rivals

- Silver Vienna

- Continental Varieties

- The West End

- American Operetta

- Broadway

- Pasticcio and Zarzuela, Italy and Russia

- Bibliography