![]()

Section ONE

Planning and Financing Infrastructure

![]()

PART ONE

Introducing Infrastructure

Part I describes the overall context for local level infrastructure with four chapters that address infrastructure issues, tell its history in the United States, describe the drivers of demand for infrastructure, and the institutions that provide infrastructure.

Chapter 1 (Infrastructure and Today’s Challenges) defines infrastructure from several perspectives before describing the major infrastructure issues facing local officials today. These include climate change, capital investment needs, and problems with the institutional arrangements for infrastructure provision and maintenance.

Chapter 2 (The Emergence of Infrastructure in the United States) begins with infrastructure provision in colonial times and moves to the rise of major transportation and water and sewer systems as the country’s economic base changed from predominantly agricultural to industrial. The impact of the Great Depression on infrastructure provision is outlined as well as the post-World War II explosive growth of infrastructure systems.

Chapter 3 (Growth, Demand and the Need for Infrastructure) focuses on the social, economic, and demographic forces driving the demand for infrastructure. It also addresses the relationship between infrastructure and growth.

Chapter 4 (Institutions of Infrastructure) concentrates on the providers of infrastructure. The segmented nature of infrastructure providers is documented, with strategies to help the practitioner create a “virtual” institution in order to maximize capital investment dollars in a more sustainable way.

![]()

chapter 1

Infrastructure and Today’s Challenges

In this chapter …

Importance to Local Practitioners

What Is Infrastructure?

The Big Picture

Current Definitions of Infrastructure

Economic Views of Infrastructure

Developers’ Definition of Infrastructure

What Are the Major Infrastructure Systems?

Environmental Systems: Water and Waste

Streets and Transportation

Community Facilities

Telecommunications, Energy, and Power

Infrastructure Challenges for the City of the Future

Climate Change and the Environment

Capital Investment Needs

Local Fiscal Pressures: Boom and Bust

Inadequate Institutional Structure

Conclusion: A New Paradigm for Infrastructure

Why Is Infrastructure Important to Local Practitioners?

Infrastructure is at the heart of vibrant, innovative cities and metropolitan areas. It is responsible for our health and safety, our prosperity, and for our ability to socialize and live together in communities. During the next 20 years, the population of the United States is expected to increase by 48 million, and by almost 50 percent by 2050. Much of this increase will be accommodated in areas without streets, roads, schools, or sanitary sewers, at the edges of existing metropolitan areas. The remainder will occur in the heart of major cities and in the inner suburbs, adding burdens to existing infrastructure already at capacity or deteriorating due to lack of maintenance or replacement. Even in relatively young cities or counties with recent growth, infrastructure built only a few decades ago can already be obsolete or in need of repair. Climate change effects have enormous implications for infrastructure. Major local responses are critical to address mitigation and adaptation needs and also to ensure that our cities and counties are ready to compete in the global economy in a sustainable way.

However, the institutions that supply infrastructure are not always prepared to deal with planning and financing needs. They are fragmented, overly bureaucratic, and single purpose in scope, when increasingly the challenge is to provide multisector responses on a regional, metropolitan, or state basis, or even between states and nations. The urgent need to reduce energy use and carbon emissions may provide the necessary stimulus to bring together the diverse interests and actors in the infrastructure sector to address these problems. This chapter begins by describing infrastructure from different points of view, then provides an overview of the major systems. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the infrastructure challenges facing local officials today.

What Is Infrastructure?

The Big Picture

Infrastructure is the built foundation of our cities and towns. It is what we cannot buy or build on our own. Infrastructure includes the common places, buildings, roads, pipes, and systems that we must join together as a society to plan, finance, and care for. In the Middle Ages, cathedrals represented the quintessential infrastructure of the time. Cathedrals were used by all and considered necessary for the maintenance of life and culture. Too big for a single generation to build, many were constructed over the course of centuries. They were built to be used by everyone, and meant to last for many generations.

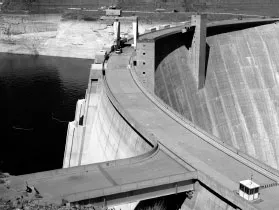

Arch Dam in Arizona

The infrastructure of our society today includes the large-scale capital structures we all share that are usually publicly financed and built. Infrastructure is capital-intensive and might not be built were it not for the intervention of government. Because infrastructure is so costly, building only “one” of it often makes sense, and usually it is owned and operated by a governmental agency.

San Mateo-Hayward Bridge in California

Infrastructure can be the invisible cable underground connecting our homes to the Internet, or the colossal dam that generates megawatts of electricity and protects downstream areas from flooding. It can be the library downtown, the sidewalk and street in a neighborhood, the local park, or the invisible network of pipes and drains underground. Infrastructure includes museums, schools, hospitals, and municipal landfills. None of these can be bought by an individual, but are shared by the whole community; they require large-scale investment, and can last for generations. They also deteriorate over time and need to be replaced or improved.

Industrial pipes leading into refining plant

Current Definitions of Infrastructure

One writer called infrastructure “the connective tissue that knits people, places, social institutions, and the natural environment into coherent urban relationships … It is shorthand for the structural underpinnings of the public realm.”1 The infrastructure historian, Joel Tarr, defines infrastructure as “the ‘sinews’ of the city: its road, bridge, and transit networks; its water and sewer lines and waste disposal facilities; its power systems; its public buildings; and its parks and recreation areas.”2

Prior to the 1980s, engineers usually called infrastructure “public works,” a term which is still used today for sewers, water and waste systems among others. Infrastructure was also a military term used to describe base camps, ports, airstrips, or other physical structures. David Perry, in his short and excellent history of infrastructure financing, notes that Presidents Washington and Jefferson referred to infrastructure as “internal improvements.”3

Construction on Portland, Oregon’s Westside Big Pipe Sewer Project at Fremont Bridge

Claire Felbinger, an infrastructure expert, writes that the term

[refers to] those physical structures and processes that support community development and enhance physical health and safety—roads, streets, bridges, water treatment and distribution systems, wastewater treatment facilities, irrigation systems, waterways, airports, and mass transit—as well as other utility services that are regulated by the public sector … [T]hey are distinguished from private-sector infrastructure such as manufacturing facilities. Hence public infrastructure traditionally includes public, physical systems that ensure a healthy quality of life and enhance movement of people, goods, and services.4

Mercer Island Crossing, Seattle, Washington

Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin assert that the configuration of infrastructure services represents the “key physical and technological assets of modern cities.” They define infrastructure as the networked systems, such as transport, streets, communications, energy, water, and waste systems that together “constitute the largest and most sophisticated technological artifacts ever devised by humans.” Graham and Marvin argue that the form of the infrastructure technology is “bundled” with the economic and cultural base of the period. Consequently, “these vast lattices of technological and material connections have been necessary to sustain the ever-expanding demands of contemporary societies for increasing levels of exchange, movement and transaction across distance.”5 This view of infrastructure as “shaping the sublime terrain for production” is echoed by architects today who use the lens of infrastructure through which to view the city.6

Maryland Bus Rapid Transit

Economic Views of Infrastructure

Economists such as W. W. Rostow used the word to designate the capital invested in major physical projects such as highways, utilities, and other government facilities.7 The U.S. Bureau of Economic Statistics distinguishes between expenditures on consumption and those on fixed assets. Fixed asset expenditures, excluding residential buildings, is defined as infrastructure in federal statistical analyses. Perry notes that the current view of public infrastructure extends beyond the capital project itself to include the entire system of planning, building, financing, and maintenance of infrastructure.8

Economists also characterize some infrastructure systems as public goods or natural monopolies, which justify public investment and/or regulation if provided by a private entity. In this case, the general public sees the merit of providing the good to everyone, because its use by those who would not normally pay for the service benefits all. For example, clean water or sewage treatment results in better health and less disease for all individuals. The transportation network is also a public good, enabling industry to produce and deliver goods that are consumed by all, and enabling workers to travel to work to produce those goods.

Natural monopolies usually refer to networked facilities covering a certain territory, often so capital-intensive that developers are deterred...