Chapter 1

Policy Definition and Gun Control

The one area where I feel that I’ve been most frustrated and most stymied…is the fact that the United States of America is the one advanced nation on earth in which we do not have sufficient common-sense, gun-safety laws. Even in the face of mass killings.

—President Barack Obama, responding to a reporter asking what his greatest frustration had been as president, July 24, 2015

THE CONTROVERSY OVER GUN CONTROL revolves around two related questions of government authority: does the government have the right to impose regulations, and, assuming the existence of such a right, should the government regulate guns? It is perfectly obvious that numerous gun control regulations already exist, from the national to the local level. Indeed, gun control opponents are quick to point out that thousands of gun laws exist throughout the country, a fact usually quoted to underscore their belief that such regulation is futile. Literature produced by the National Rifle Association (NRA) mentions “an estimated twenty thousand local, state, and federal firearms laws,” but that oft-repeated number is incorrect. A careful recent count of gun laws in the United States produced an actual number of about four hundred.1 Gun control opponents also argue that further gun restrictions could impinge on constitutional rights and the innate rights of the citizenry in a free nation. These arguments reappear in every presidential election. In 2008, for example, Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama was pilloried for his past support of gun regulations, and gun rights advocates translated that support as alarmist claims that Obama would be a “gun-grabber” as president. Obama’s response was emphatic that he supported Second Amendment rights and had no intention of interfering with legitimate gun activities, including hunting and sporting. Yet Obama’s reassurances did not assuage the critics. In fact, the Brady Campaign, a pro-gun control organization, gave Obama a failing grade of “F” for his performance on the gun issue during his first term. After his 2012 re-election, Obama did press for tougher national gun laws in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, but that effort fell short (see Chapter 5).

Competing values about guns, safety, and freedom clashed in the aftermath of the worst mass shooting of modern times at a nightclub in Orlando, Florida. American-born Omar Mateen, a twenty-nine-year-old son of Afghani immigrants, entered the Pulse nightclub in the early hours of June 12, 2016, armed with a SIG Sauer assault-style rifle and a Glock semi-automatic handgun. Both were legally purchased. Most of the 49 people killed and 53 wounded were shot shortly after his entry. After several hours, police used an armored vehicle to batter down a wall, leading to the shooter’s death by police. Key questions of motive swirled around this heinous crime. During the standoff, Mateen called police to state his allegiance to the Islamic State. In 2013 and 2014, the FBI investigated Mateen as a possible terrorist suspect, but failed to find sufficient evidence. After his death, no actual links to terrorist groups were found. In a different possible motive, Mateen may have had mixed feelings about his own sexuality. The Pulse was considered a gay nightclub, and Mateen had visited the club several times as well as social media sites for making connections with gay men. Several witnesses claimed that Mateen had sought out personal relations with male nightclub patrons. Was this a case of a terrorist who slipped through government screening? Was that simply an excuse by Mateen for his real motive, related to doubts about his own sexual identity? How aggressive should the government be in trying to identify those with political or other motives for killing random innocent civilians?2

Before proceeding with key questions about guns and American society, we must begin with the role and purpose of government regulation.

Regulation, Public Order, and Public Policy

The fundamental purpose of government—indeed, its first purpose—is to establish and maintain order. As many political thinkers have noted, human existence before the establishment of governments was chaotic and anarchic. Writing in the seventeenth century, the British political theorist Thomas Hobbes noted in his Leviathan that life in such a “state of nature” was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” The only “law” in this situation was that of self-preservation, when one could expect only the “war” of “every man, against every man.” To stave off such an anarchic condition, people formed governments, to which citizens traded some of their freedom, including the “freedom” to kill or be killed, in exchange for the order of civil society. In such a “civil state,” according to Hobbes, “there is a power set up to constrain those that would otherwise violate their faith.”

Writing several decades after Hobbes, the British political thinker John Locke in his Of Civil Government concurred, noting that “God hath certainly appointed government to restrain the partiality and violence of men. I easily grant that civil government is the proper remedy for the inconveniences of the state of nature.” That we in America largely take the value of order for granted is a testament to the remarkable stability of American life.3 Order is not the only priority for government, of course, because democratic nations also value freedom and the protection of basic rights and must continually strive to strike an appropriate balance between these values.4 Nevertheless, order is the first purpose of government because without order there can be no freedom in society (aside from the “freedom” of anarchy to which Hobbes and Locke referred). As the political scientist Samuel Huntington once noted, “men may, of course, have order without liberty, but they cannot have liberty without order.”5 And, as James Madison wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1788, “It is a melancholy reflection that liberty should be equally exposed to danger whether the Government have too much or too little power.”

Governments’ maintenance of public order occurs through public policy, defined most simply as “whatever governments choose to do or not to do.”6 The interesting semantic fact that “policy” has the same linguistic root as “police” underscores the close link between order and public policy.7 Note the link between the two in this definition of public policy offered by the British constitutionalist William Blackstone in 1769:

the due regulation and domestic order of the kingdom, whereby the inhabitants of the State, like members of a well-governed family, are bound to conform their general behavior to the rules of propriety, good neighborhood, and good manners, and to be decent, industrious, and inoffensive in their respective stations.

The techniques or tools of public policy take many forms, from the dispensing of benefits to strict regulation of individual conduct. Yet basic questions of public order usually involve direct regulation—power exercised by the government “for the protection of the health, safety, and morals of their citizens.”8 Beyond the simple maintenance of order, “government is the guarantor of the public good. Ideally, this is achieved as government regulates private functions to maximize public welfare.”9 The regulation of individual conduct may include that considered harmful to others, such as driving under the influence of alcohol, or conduct considered immoral, such as gambling or prostitution.10 This returns us to the question of the regulation of firearms. (In this analysis “guns” and “firearms” are treated as synonymous.) The fierce and protracted debate over gun control raises a variety of issues about individual behavior and the role of the government. Nevertheless, at its core the gun debate turns on a single, central question of public policy as it relates to both order and personal conduct: should gun possession and use be significantly regulated? This central question of public policy guides the organization of this book.

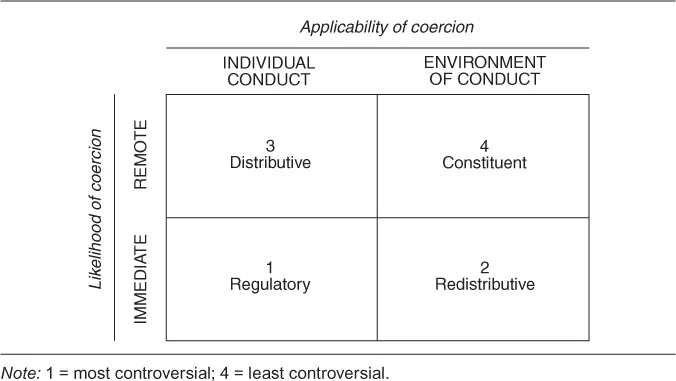

Guns and Regulation

Why has gun control been such a difficult, controversial, and intractable issue in American politics? The first answer is because of the nature of regulation. Whenever the government seeks to apply its coercive powers directly to shape individual conduct, the prospect of controversy is great, especially in a nation with a long tradition of individualism. According to the policy analyst Theodore J. Lowi, when the likelihood of government coercion is immediate—that is, when the behavior of individual citizens is directly affected, as in the case of regulation—the prospect of controversy is high.11 When the likelihood of government coercion is remote—that is, when the primary purpose of the policy in question is, say, to provide benefits rather than regulate individual conduct—the prospect of controversy is low. Examples of policies in which government coercion is low include public works projects (construction of roads, harbors, buildings, and the like) and subsidies to farmers (labeled “distributive”; see Figure 1.1). Government can influence behavior by providing these benefits, but the primary emphasis is on the awarding of benefits, not the shaping of conduct.

In addition to immediate coercion, regulatory policy shares a characteristic that fans the flames of political controversy: it seeks to control individual conduct. When the government imposes highway safety regulations, pure food and drug requirements, cable television rates, criminal laws, or laws regulating abortions, it is regulating the conduct of individuals (not only individual citizens but also individual companies or other entities). Because of these direct consequences to individuals, regulatory policies are more controversial than policies that seek to shape the “environment of conduct,” such as fiscal and monetary policy, the progressive income tax, and welfare programs. Even though these latter policies (labeled “redistributive”; see Figure 1.1) affect individual citizens, the policies themselves are designed to shape broad classes or groups of people—the poor, certain categories of wage earners, homeowners—or even the entire society.12 Thus, the individual citizen feels the hand of government less directly than policy designed to regulate the conduct of individuals. The fourth and least controversial form of policy is that for which government coercion is remote and seeks to shape the environment of conduct. Labeled “constituent” policy (see Figure 1.1), such policies include, for example, those pertaining to the administration of the government, the budgeting process, and the civil service.

Figure 1.1 summarizes the relationship between these four kinds of policies. Among the four, regulatory policy is the most likely to spawn controversy. Immediate coercion applied to individual conduct usually involves specific rules or sanctions with accompanying punishments, such as fines or imprisonment. The other kinds of policies are progressively less likely to include such specific and individually felt sanctions, as reflected in the numerical rank ordering in Figure 1.1.13

We can make an even finer distinction within the category of regulatory policy by distinguishing between two primary types of regulation: economic regulation and social regulation.14 Economic regulation dates back to the late nineteenth century, when the national government began to become involved with regulating elements of the nation’s economy. The first modern regulatory agency, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), was created in 1887 to regulate railroad rates, control prices affecting consumers, require the publication of rail rates, and bar collusive practices.15 Economic regulation then accelerated in the twentieth century, incorporating a wide variety of business, market, and economic sectors.

Figure 1.1 Government Coercion and Political Controversy among Types of Policy

Social regulation dates back many decades. Government,...