eBook - ePub

Vestibular Processing Dysfunction in Children

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Vestibular Processing Dysfunction in Children

About this book

This collection of chapters is intended to help expand, organize, and enhance understanding of the scientific and clinical relevance of vestibular-related research. Articles present a well-developed body of research with both clinical and theoretical implications, including a variety of studies contributed by individuals from different backgrounds and with diverse orientations. This collection contains anatomical investigations, analyses of instruments designed to clinically assess spedcific functions, descriptive bahavioral studies, intervention research , literature reviews and analyses which place the existing research within the broader contex of scientific literature.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Vestibular System: An Overview of Structure and Function

INTRODUCTION

The vestibular system is phylogenetically old and has neuroanatomical connections with many other systems, both motor and sensory. Some basic physiological interactions of the vestibular system with other systems are partially understood; however, the full impact of vestibular input on central nervous system (CNS) function is not known.

This chapter is limited to basic anatomy and physiology of some of the better understood portions of the vestibular system. The sensory end organ in the inner ear functions as a transducer of vestibular-appropriate sensory stimuli. The vestibular nuclear complex consists of a number of nuclei and cell groups, but only the four major nuclei are discussed. Portions of the cerebellum, some of which receive primary vestibular afferents, also are involved in vestibular reflexes. Descending vestibular activity is discussed in terms of the vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts which appear to share in controlling many postural reflexes. Long descending pathways apparently are more responsive to otolith rather than to semicircular canal input. Ascending pathways play a major role in controlling eye movements in response to movements of the head. Ascending pathways primarily reflect semicircular canal signals, with some otolith influence. Since the vestibular input functions to help maintain a stable retinal image, visual feedback and the cerebellum are important factors in the vestibulo-ocular reflex.

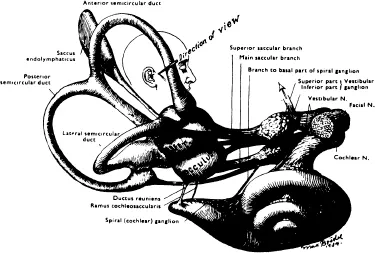

END ORGAN

The ear may be divided into three parts: (1) the outer ear, (2) the middle ear, and (3) the inner ear. The outer ear consists of the pinna and the external auditory canal which terminates medially at the tympanic membrane. The middle ear is an air-filled cavity containing the ossicles which conduct auditory vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear. The external and middle ears are concerned only with hearing, but the inner ear functions for both hearing and equilibrium. The inner ear is made up of a series of fluid-filled chambers and ducts (Figure 1). One fluid-filled space lies within the other. The outer space is the perilymphatic space while the inner space is the endolymphatic space. The perilymphatic space is filled with a fluid called perilymph, and the endolymphatic space is filled with endolymph. The tissue surrounding the perilymphatic space is part of the temporal bone. Embryologically, the cartilagenous precursor of the bone tissue forms a capsule immediately around the perilymphatic space and this tissue is called the osseous labyrinth.1 The thin membrane separating the perilymphatic space from the endolymphatic space is the membranous labyrinth. The neuroepithelium for the auditory and vestibular portions of the ear is found within the endolymphatic space.

The vestibular portion of the ear has three parts: (1) the utricle, (2) the saccule, and (3) the semicircular canals. The utricle and saccule lie just medial and posterior to the cochlea, or auditory portion of the ear. The endolymph of the utricle and saccule is continuous with that of the semicircular canals and of the scala media of the cochlea. The utricle and saccule are almost identical, both anatomically and physiologically, and are often collectively referred to as the otolith organ. The term otolith (“ear stone”) refers to thousands of calcium carbonate crystals (otolithic or statolithic crystals) which are imbedded in the surface of the epithelium of these two sensory organs. The neuroepithelium of the otolith organ, including otolithic crystals, is called the macula.

FIGURE 12. The endolymph-filled membranous labyrinth.

Each ear contains three semicircular canals. Each is paired with another canal in the opposite ear. The membranous semicircular canals consist of an endolymph-filled duct and ampulla. The duct is curved and forms the “semicircle”. It opens at one end into the utricle and the other end joins with its ampulla. The ampulla contains the neuroepithelium: the crista ampullaris. The crista ampullaris, is in many ways, similar to the macula of the otolith organ.

The structure of both the otolith and semicircular canal neuroepithelium is basically the same. The neuroepithelium consists of sensory hair cells, supportive cells, nerve fibers, nerve endings and superstructural elements such as the cupula and otolithic crystals, which can be considered to function as mechanical transducers to transform angular and linear acceleration into pattern-specific afferent nerve signals.

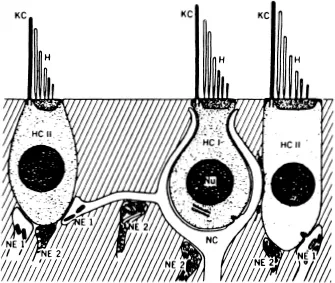

Two types of vestibular sensory hair cells have been identified (Figure 2). The Type II hair cell is phylogenetically more primitive and its cell body takes on a columnar appearance. The peripheral processes of several afferent neurons make direct synaptic contact with the Type II hair cell surface. The Type I hair cell has a light-bulb shape, and a peripheral afferent process forms an expanded envelope, or calyx, that intimately envelops the surface of the hair cell. Efferent fibers also interact with both hair cell types. Efferent fibers terminate directly upon the body of cell Type II, thus forming a synapse peripheral to the hair cell-afferent synapse. Efferent fibers to the Type I cell, however, make contact with the afferent calyx, not the surface of the Type I hair cell.

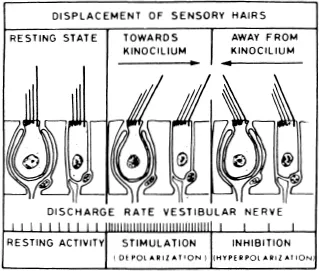

Cilia project from the surface of the cuticular plate of each hair cell. From 60 to 100 stereocilia but only one kinocilium project from the surface of each hair cell. The stereocilia are homogenous in cross-section, are rather stiff and are anchored with small rootlets which penetrate through the cuticle. The kinocilium is longer than the longest stereocilium and is found on one side of the bundle of stereocilia. The asymmetry produced by the location of the kinocilium produces a polarization of each hair cell. In the crista of the horizontal semicircular canal, the kinocilium of each hair cell is located on the utricular side of the ampulla, that is, toward the midline; therefore, the polarity of each hair cell is extended to provide polarity of each crista ampullaris. The polarity is reversed in the vertical canal cristae. In the cristae of the vertical canals, the kinocilia are all located on the distal pole of the hair cells, toward the semicircular canal duct.4

Electrophysiological experiments on the semicircular canals show the consequence of the anatomical polarity.5,6 In a majority of units sampled, spontaneous activity was found when the cupula was in the resting position (Figure 3). When the cupula was deflected in the direction of the kinocilium, the rate of discharge increased. When deflected in the direction away from the kinocilium, the level of spontaneous activity decreased.

FIGURE 23. Schematic diagram of the vestibular neuroepithelial hair cell Type I (HCI) and hair cell Type II (HCII) with sensory endings (NEI) on hair cell Type II and afferent calyx (NC) on hair cell Type I. Efferent terminals (NE2) are shown synapsing on both hair cell surfaces and on afferent fibers. Nu, nucleus; KC, kinocilium; H, stereocilia.

FIGURE 34. Primary ampullary afferents show spontaneous discharge while the cupula is in a resting condition (left). If cupula deflection deflects the cilia toward the kinocilia, discharge rate increases (middle). When deflected away from the kinocilia, the discharge rate decreases (right).

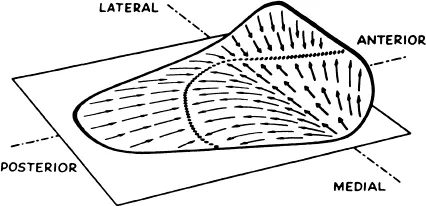

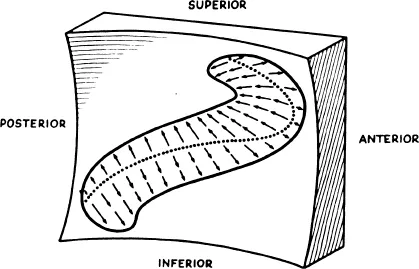

The polarization of hair cells of the macula of the utricule and saccule is more complex. Hair cells in any one area of the macula tend to be oriented in the same direction; however, over the entire surface a changing pattern of polarization is seen. Over the surface of the utricular macula, directionality dictated by the kinocilia forms a laterally directed, fan-like pattern beginning at the medial edge up to a curved boundary line which passes near the center of the macula (Figure 4). Lateral to the boundary line, kinocilia are medially directed.

A different pattern exists on the macula of the saccule (Figure 5). A curving boundary line courses from superior to inferior across the surface; however, the kinocilia do not face each other across the boundary line as in the utricle, but face away from each other. In the case of both maculae, the boundary line tends to coincide with the striola where smaller otolithic crystals are found. The small crystals coupled with the opposing polarity along the boundary line suggest a specialized region of the macula.8

The neuroepithelium, or macula, of the otolith organ consists of a single layer of neurosensory hair cells interspersed with supporting cells, all on a basement membrane. Cilia project from the surface of each neurosensory hair cell and project into a gelatinous substance which lies as a layer above the neurosensory and supporting cells. The otolithic crystals form the most superficial layer of the macula. The otolith crystals are imbedded in the surface of the gelatinous substance and apparently are covered with some kind of adhesive which keeps them from breaking away from each other and from the gelatinous substance.

FIGURE 47. The plane of the surface of the utricle approximates the horizontal plane when the head is tipped forward 25°. The anterior third of the surface is raised slightly. The arrows indicate the direction of polarization dictated by the location of kinocilia.

The otolith organ functions to detect linear acceleration. Linear acceleration is a change in linear velocity, and is experienced, for example, when your car accelerates away from a stoplight, or decelerates at a stop sign. Linear acceleration is also experienced as we go up or down in an elevator. In fact, since gravity is a form of linear acceleration, the otolith organ is sensitive to sustained head tilt in any position. Linear acceleration is detected because the otolithic crystals are more dense than the en-dolymph fluid or the gelatinous layer in which they are imbedded. A shearing force which bends the sensory hairs triggers depolarization of the hair cells. The otolith organ, because of the patterned arrangement of the cilia, detects both the direction and amplitude of linear acceleration. The distribution of the receptors allows the otolith system to detect linear acceleration in the fore-aft (X axis), lateral (Y axis), and vertical (Z axis) directions. Primary otolith afferents respond to centrifugal sinusoidal stimulation over a frequency range of 0.006 to 2.0 Hertz (Hz or cycles per second).9 They do not respond when the otolith organ is exposed to angular acceleration.10

FIGURE 57. The plane of the surface of the saccule is approximately vertical. The surface is slightly concave, and the kinocilia are oriented away from a curving centerline as indicated by the arrows.

The surface of the macula of the utricu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Message from the Editors

- The Vestibular System: An Overview of Structure and Function

- Assessment of Vestibular Function in Children

- Reliability and Clinical Significance of the Southern California Postrotary Nystagmus Test

- Developmental Status of Children Exhibiting Postrotatory Nystagmus Durations of Zero Seconds

- Immediate Effects of Waterbed Flotation on Approach and Avoidance Behaviors of Premature Infants

- Effects of Controlled Rotary Vestibular Stimulation on the Motor Performance of Infants with Down Syndrome

- A Meta-Analysis of Applied Vestibular Stimulation Research

- Vestibular Stimulation as Early Experience: Historical Perspectives and Research Implications

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Vestibular Processing Dysfunction in Children by Kenneth J Ottenbacher,Margaret A Short Degraft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.